The Truth About The GM/Chrysler Dealer Cull

It is not at all clear that the greatly accelerated pace of the dealership closings during one of the most severe economic downturns in our nation’s history was either necessary for the sake of the companies’ economic survival or prudent for the sake of the nation’s economic recovery

Whoops! Who could have thought that the biggest political fight of the bailout era was picked over something never really needed to happen. At least, not according to the SIGTARP, the Special Inspector General for TARP, Neil Barovsky. In his latest report on the GM and Chrysler dealer cull [ full document in PDF here], Barovsky explodes a lot of the myths surrounding the move to accelerate dealer closings, and even goes so far as to assign real blame… and not to GM or Chrysler either.

Which is not to say that GM and Chrysler’s behavior wasn’t worth noting. The SIGTARP report points out that there were real discrepancies between the way the two firms handled the dealer cull.

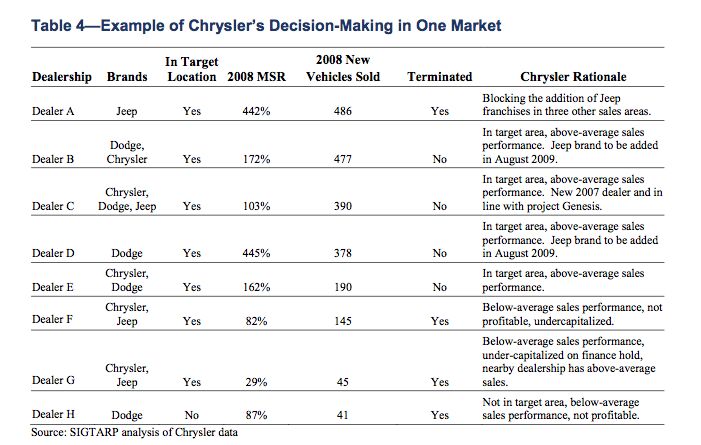

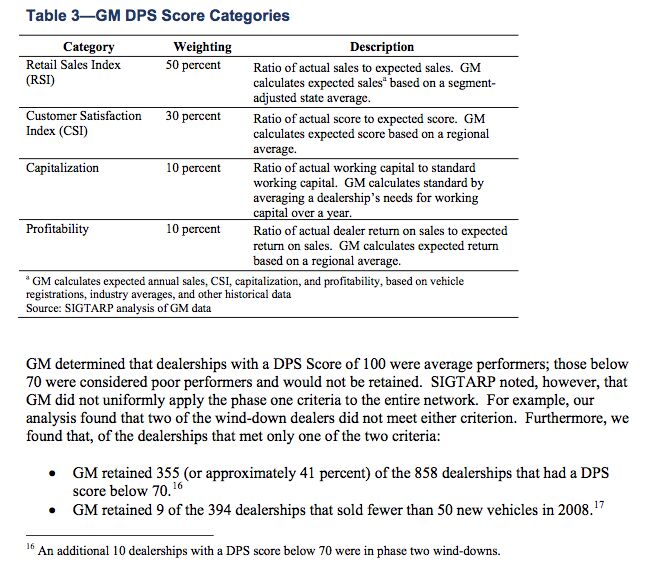

Chrysler decided which dealerships to terminate based on case-by-case, market-by-market determinations, and did not offer an appeals process. SIGTARP did not identify any instances in which Chrysler’s termination decision varied from its stated, albeit subjective selection criteria. GM’s approach, which was conducted in two phases, was purportedly more objective, and it offered an appeals process. However, SIGTARP found that GM did not consistently follow its stated criteria and that there was little or no documentation of the decision-making process to terminate or retain dealerships with similar profiles, or of the appeals process.

Which would you rather have you business be at the mercy of: a consistently subjective cull or an inconsistently objective cull? Though GM and Chrysler took different approaches to the dealer cull, both have had to back off under heavy political pressure brought to bear by the congressionally-mandated arbitration process. But now we’re getting ahead of ourselves. First we need to look at how the dealer cull happened.

Like so many stories of government run amok, the GM and Chrysler dealer culls were dreamed up by smart people who had locked themselves into a room until they fixed a problem; in this case, turning GM and Chrysler into viable companies. As they sought solutions, Obama’s Auto Team heard advice from a number of financial and industry experts, many of whom identified dealer network size as a major obstacle to GM and Chrysler’s long-term viability.

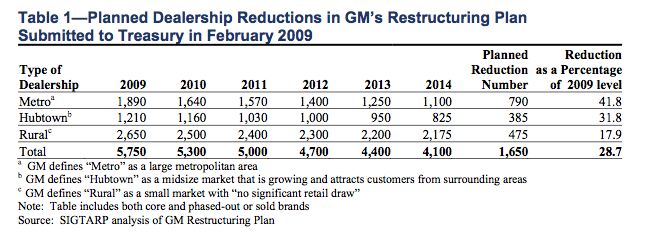

Indeed, GM and Chrysler had already both been working on dealer reductions for years before the Auto Team was even assembled. In their February 2009 viability plans, GM submitted accelerated dealer reduction plans (above), confirming the Auto Team’s growing consensus that this was a key factor in the restructuring of the troubled automakers. Chrysler did not give details about dealer reductions at that point, and the Auto Team would go on to reject both plans, in part because neither culled dealers fast enough. Barovsky explains:

In its restructuring plan, GM initially proposed closing 1,650 dealers by 2014, but following the Auto Team’s response, it instead identified 1,454 dealerships to be wound down by 2010 during its 2009 bankruptcy proceedings. Chrysler also accelerated its dealership terminations – it had planned to reduce its network from 3,181 in 2009 to about 2,000 dealerships by 2014 through Project Genesis (its effort at consolidating dealerships) and instead immediately terminated 789 dealerships during bankruptcy proceedings.

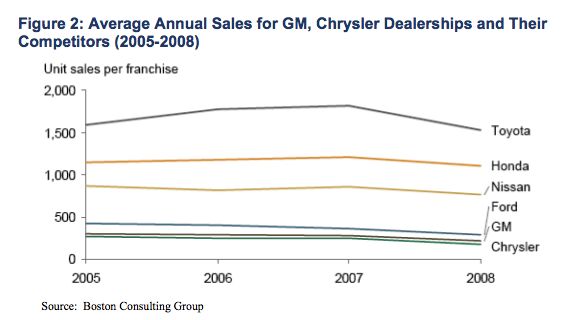

But before that happened, the Auto Team spent several months convincing itself (with the help of outside consultants) that an accelerated dealer cull had to take place. With Boston Consulting Group and Rothschild advising, the Auto team began lured with a perennially popular concept in the auto industry (until more recently, anyway): be more like Toyota.

Much of the information that the Auto Team received about the benefits for dealership determinations was based on the “Toyota Model,” which suggested that smaller dealership networks would reduce competition among dealerships and increase sales volume for the remaining dealerships. It was believed that this would then allow the dealerships to invest more in their facilities, thus improving the brand equity of GM and Chrysler.

Surely there was some validity to this approach. It was certainly a theory that floated around TTAC during and prior to the bailout, but

A former Chrysler Deputy CEO told SIGTARP that the “Toyota model” studied by the Auto Team — that fewer dealerships, located mostly in metro areas, would lead to higher sales and profitability for the remaining dealerships — would not work for Chrysler. This is because Chrysler sells trucks in rural markets as well as cars in Midwestern states where imported cars are less popular. He said that Chrysler will “never” get to the same throughput level as its import competitors. The former Chrysler Deputy CEO likened applying the Toyota model to Chrysler to “trying to turn our sons into daughters.”

In short, graphs like this one are a fact of life for a Chrysler corporation.

In fact, some of the only consultants to complain about the accelerated cull to the Auto Team were JD Power analysts who argued that, especially in the case of Chrysler, the move would “create a wave of chaos amidst [an economic] crisis.” The Center for Automotive Research also pointed out that culling rural dealers ignored the oversaturation of certain urban markets and attacked GM and CHrysler’s strength in rural markets.

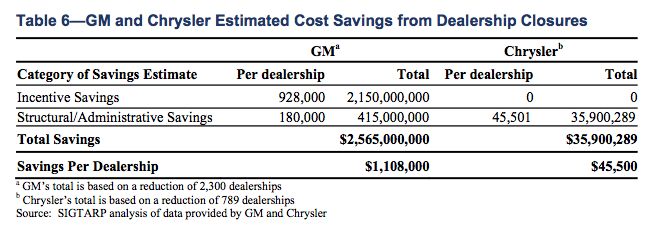

But the Auto Team and Treasury had their course so inexorably plotted out that the Auto Team didn’t even analyze the job loss impacts of an accelerated cull until it had already decided to push it through. And on the other side of the decision-making analysis, the financial benefits for the dealer cull were almost entirely window dressing. GM and Chrysler both submitted estimated cost savings of shutting down dealerships (below), but they only did so in order to be able to answer questions from congress.

As you can see, most of GM’s claimed cost savings were listed in the form of a nearly million-dollar incentive saving… which GM would have to pay anyway if its remaining dealers improved their volume per the plan. Barovsky reveals that:

key members of the Auto Team — including Messrs. Rattner and Bloom — stated that they did not consider cost savings to be a factor in determining the need for dealership closures. Nevertheless, GM officials stated that they developed the cost-savings estimate shown in Table 6 after being “pressed” during meetings with congressional representatives to explain the cost savings that would result from the dealership terminations. A Chrysler official said that the cost savings estimates had been originally developed in 2006 and 2007, before the issue of dealership terminations arose, and were updated based on SIGTARP’s request. GM officials reiterated that the plan to reduce dealerships was based on making the remaining dealership network more profitable by increasing their sales volume. In fact, when asked by SIGTARP what GM will save by closing any particular dealership, one GM official stated the answer is usually “not one damn cent.”

Furthermore, a GM official stated that removing a dealership from the network does not save money for GM—it might even cost GM money—and that savings cannot be attributed or assigned to any one dealership. According to one GM official, it was a “math exercise” to assign a savings amount to one dealership; it was difficult to estimate savings for a particular dealership because the savings are expected to be achieved when the entire dealership network plan is accomplished.

GM did also indicate that it would save $200m on local advertising assistance, as part of a total $415m annual administrative cost savings associated with the dealer cull (Chrysler estimated administrative savings at $36m). Regardless, neither the Auto Team nor Treasury appears to have considered these estimated costs significant factors in the decision to accelerate GM and Chrysler’s dealer culls, nor did GM or Chrysler use them for any part of their implementation of the cull.

How GM and Chrysler went about the dealer culls was something of a running mystery for some time, but if any questions remain, Barovsky’s report can surely help answer them. In essence, GM used a set formula for the cull, but used it inconsistently while Chrysler developed an entirely subjective system for determining a dealer’s viability, and analyzed each dealership market-by-market. Both screwed up, both made enemies and alienated long-standing dealers. Chrysler did so in a completely mystifying manner (above) whereas GM allowed dealers who fell beneath its standards (below) to survive because “they were recently appointed, were key wholesale parts dealers, or were minority- or woman-owned dealerships.”

Barovsky’s conclusions about this fantastic brew-ha-ha are understandably bleak.

Here, before the Auto Team rejected GM’s original, more gradual termination plan as an obstacle to its continued viability and then encouraged the companies to accelerate their planned dealership closures in order to take advantage of bankruptcy proceedings, Treasury (a) should have taken every reasonable step to ensure that accelerating the dealership terminations was truly necessary for the long-term viability of the companies and (b) should have at least considered whether the benefits to the companies from the accelerated terminations outweighed the costs to the economy that would result from potentially tens of thousands of accelerated job losses. The record is not at all clear that Treasury did either. The anticipated benefits to the companies of accelerated terminations were based almost entirely on the not-universally-accepted theory that an immediate decrease in dealerships would make them similar to their foreign competitors and therefore improve the companies’ profitability, and the theory arguably did not take into account some of the unique circumstances of the domestic companies’ dealership networks. Although Treasury consulted with several experts on the subject, it undertook no market studies to test the counterintuitive theory until after making its Viability Determination. More importantly, there was no effort even to quantify the number of job losses that the Auto Team’s decision would contribute to until after the decision was made, and the effect on the broader economy caused by accelerated dealership terminations similarly was not sufficiently considered.

Stated another way, at a time when the country was experiencing the worst economic downturn in generations and the Government was asking its taxpayers to support a $787 billion stimulus package designed primarily to preserve jobs, Treasury made a series of decisions that may have substantially contributed to the accelerated shuttering of thousands of small businesses and thereby potentially adding tens of thousands of workers to the already lengthy unemployment

Luckily the odds of this ever happening again are not good. On the other hand, why risk it? Ladies and gentlemen, listen to the SIGTARP.

More by Edward Niedermeyer

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Jeff Overall I prefer the 59 GM cars to the 58s because of less chrome but I have a new appreciation of the 58 Cadillac Eldorados after reading this series. I use to not like the 58 Eldorados but I now don't mind them. Overall I prefer the 55-57s GMs over most of the 58-60s GMs. For the most part I like the 61 GMs. Chryslers I like the 57 and 58s. Fords I liked the 55 thru 57s but the 58s and 59s not as much with the exception of Mercury which I for the most part like all those. As the 60s progressed the tail fins started to go away and the amount of chrome was reduced. More understated.

- Theflyersfan Nissan could have the best auto lineup of any carmaker (they don't), but until they improve one major issue, the best cars out there won't matter. That is the dealership experience. Year after year in multiple customer service surveys from groups like JD Power and CR, Nissan frequency scrapes the bottom. Personally, I really like the never seen new Z, but after having several truly awful Nissan dealer experiences, my shadow will never darken a Nissan showroom. I'm painting with broad strokes here, but maybe it is so ingrained in their culture to try to take advantage of people who might not be savvy enough in the buying experience that they by default treat everyone like idiots and saps. All of this has to be frustrating to Nissan HQ as they are improving their lineup but their dealers drag them down.

- SPPPP I am actually a pretty big Alfa fan ... and that is why I hate this car.

- SCE to AUX They're spending billions on this venture, so I hope so.Investing during a lull in the EV market seems like a smart move - "buy low, sell high" and all that.Key for Honda will be achieving high efficiency in its EVs, something not everybody can do.

- ChristianWimmer It might be overpriced for most, but probably not for the affluent city-dwellers who these are targeted at - we have tons of them in Munich where I live so I “get it”. I just think these look so terribly cheap and weird from a design POV.

Comments

Join the conversation

Looking at the example of Chrysler dealers kept and terminated I don't see much of the "subjective criteria" mentioned in the report. You are either under capitalized or you are not. You either meet your sales targets or you don't. If those standards were arbitrary you would have a point but I don't think they were as it was the company's desire to survive as a going concern and whacking random dealers for the fun of it is not the way to achieve that. The only argument you could make for subjectivity was for dealer A. His sales were good but he was blocking the awarding of Jeep franchises to other dealers and preventing the progress of Project Genesis.

"dealer culls were dreamed up by smart people who had locked themselves into a room until they fixed a problem; in this case, turning GM and Chrysler into viable companies" A-HA HA HA HA HA HA! Wait, wait... BWAHAHAHA HAHA HAHAHA HA. Whew. Hi-larious.