Jeff Davis Vs Abe Lincoln: The Highway Edition

When considering the way some folks apply modern values to historical personages and events, I often think of two historical truths from the world of fiction. William Faulkner gave us, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” while L.P. Hartley opened his novel The Go-Between with, “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.”

History resonates and rhymes, but things do change.

In America we are currently having a raging debate over whether or not prior remembrances of the past will be effaced because the people remembered were flawed human beings who, in some cases, embraced causes or beliefs many people today consider to be odious. Most recently, Charlottesville, Virginia, has been ground zero for the controversy, with extremists latching on to the issue — resulting in a horrific vehicular homicide.

Peripherally to the events in Chalottesville, the city council of Alexandria, Virginia, has voted to rename the section of the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway that travels through their city.

How that road got named after the president of the Confederate States of America more than a century ago — and nearly 50 years after the end of the Civil War — is an interesting exploration into culture, race, and the history of transportation in America.

Before Jefferson Davis was elected president of the CSA, Abraham Lincoln was the duly elected president of the United States of America. Before there was a Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway, or at least before it was proposed by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (the CSA’s analog to the Daughters of the American Revolution), there was the Lincoln Highway project.

Henry Ford introduced the first Ford Motor Co. automobile in 1903. Ten years later, in 1913, Ford sold over 170,000 Model Ts, more than doubling his production from the year before. In 1913, nearly one million motor vehicles were registered by state governments in the U.S., a figure that would climb by more than a million cars a year until the depths of the Great Depression in 1932. America was on the road (FoMoCo’s headquarters’ address in Dearborn, Michigan is still 1 American Road).

In 1913, though, America’s roads were, for the most part, undeveloped, particularly those that would allow transportation between cities. Into the 20th century, goods and people moved by rail, not roads. Most improved roads were found in the cities. Some counties and townships maintained what were called “market roads” to help farmers get produce to towns, but many states had constitutional prohibitions against expenditures on internal improvements, including roads. Federal highway funding wouldn’t be seen as a need until World War I and really didn’t mean much until the ’20s.

Before World War I, fewer than 9 percent of the country’s roughly 2.2 million miles of rural roads were “improved.” How improved they really were is an open question, as the category included gravel, stone, sand-clay, and oiled-dirt roads, as well as paved brick, bituminous (asphalt), and the few concrete roads there were. The first full mile of concrete roadway in America had only recently been constructed in 1909 on Detroit’s Woodward Avenue.

Until Henry Ford proved his revolutionary concept that technology was most profitable when selling it to the masses, not treating it as a toy for the wealthy, there was substantial opposition to intercity and interstate highways. Some called them “peacock alleys” because only the idle rich had the leisure time to spend touring the countryside in their expensive motorcars. The success of the Model T changed all that, stimulating a number of efforts to improve America’s highways.

The Lincoln Highway was the brainchild of Carl G. Fisher (just one of the man’s many ideas). Fisher manufactured the Prest-O-Lite carbide gas headlights that helped give “brass era” motorcars their moniker, he built what is now known as Indianapolis Motor Speedway, home of the world’s most famous motorsports event, and also developed Miami Beach.

Fisher loved and raced cars and in building Miami Beach he created one of America’s great vacation destinations. Still, he knew that, “The automobile won’t get anywhere until it has good roads to run on.” In 1912 Fisher started organizing what became the Lincoln Highway Association, dedicated to building a “Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway” stretching from New York’s Times Square to Lincoln Park in San Francisco. Fisher, who understood what we now call infrastructure, wanted the Lincoln Highway to be a catalyst for other roadbuilding projects. He wanted the Lincoln Highway to stimulate “the building of enduring highways everywhere that will not only be a credit to the American people but that will also mean much to American agriculture and American commerce.”

In September of 1912, Fisher held a dinner in Indianapolis, hosting many leading figures in the booming automobile industry and encouraged them to get behind his dream of an privately funded improved coast-to-coast road that would be completed in time for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition then being planned for San Francisco. Fisher thought it would cost $10 million. He soon secured pledges of $1 million from his friends in the car biz, with the notable exception of Henry Ford, who thought it was the role of government to build intercity roads. In time, Fisher would come to see the wisdom of Ford’s position. It didn’t take three years to complete the Lincoln Highway; it took almost three decades.

In July of 1913, after Congress decided to fund the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. instead of a proposed Lincoln Memorial Road from the nation’s capitol to Gettysburg, PA, Fisher’s group decided to name the road the Lincoln Highway and established the Lincoln Highway Association to promote it. They weren’t really going to build a road from coast to coast, rather they were going to create a route by connecting America’s patchwork of existing roads. That route was announced in September 1913, disappointing some city leaders whose towns the route bypassed. Henry Joy, the head of Packard Motor Car Co., had taken a leadership role along with Fisher and persuaded the group to make as direct a route as possible. The initial length of the Lincoln Highway was 3,389 miles and contained many historic roads, including the Lancaster Pike in Pennsylvania, the Mormon Trail, the routes of the Overland Stage Line and Pony Express, and the Donner Pass in California.

To promote the effort, and choose a route through the western half of the country, Fisher and company spent 34 days in 17 cars and two trucks driving from Indianapolis to San Francisco in what was billed as the Trail-Blazer tour.

The Lincoln Highway was dedicated on October 31, 1913, with ceremonies held in hundreds of towns and cities in the 13 states along the route. The LHA estimated that the cross-country trip would take three to four weeks at an average driving speed of 19 miles an hour. The route was marked with red, white and blue signs.

As mentioned, Fisher came to agree with Henry Ford that privately funding road construction wasn’t going to work. By September of 1912, Fisher told a friend in a letter, that “the highways of America are built chiefly of politics…” Most of the LHA’s activities were promotional and Fisher and his associates were masters at getting publicity. Besides embedding reporters from the Hearst syndicate, the Chicago Tribune, and the Indianapolis Star as well as telegraph companies in the Trail-Blazer tour, Fisher hired F.T. Grenells, the Detroit Free Press’ city editor, to work part time as the LHA’s PR man.

Donations were solicited and famous supporters were cultivated, among them Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Edison, and then President Woodrow Wilson. When Inuit children in Anvik, Alaska Territory, described as “Esquimaux”, contributed 14 pennies to the effort, their contributions and photos of the coins were widely publicized.

While the LHA could not afford to pay to build the Lincoln Highway, they did build short sections of the route, called Seedling Miles, “to demonstrate the desirability of this permanent type of road construction” and “crystallize public sentiment” for “further construction of the same character.” They worked with an LHA sponsor, the Portland Cement Association, to get cement companies to donate materials for those paving jobs. Improving paving technology was part of the LHA’s efforts, and in 1920, they built an Ideal Section of a Seedling Mile in Lake County, Indiana, to demonstrate a road that would be suitable for decades. Many of the design features of that Ideal Section are still in use today, like banked curves, guardrails and reinforced concrete that was 10 inches thick. The roadway was meant to last 20 years but is still in use today, almost 100 years later.

In 1919, the Lincoln Highway Association promoted the first transcontinental motor convoy undertaken by the United States Army. It took the convoy almost two months to get from Washington to San Francisco, but the trip generated huge publicity and encouraged the federal government to start funding road construction. The most important effect of that convoy was delayed more than 30 years, though. One of the Army officers was a Lt. Colonel named Dwight David Eisenhower. That trip, and seeing Germany’s network of autobahns, persuaded Eisenhower to spur the creation of the Federal Highway Trust Fund and our interstate highway system.

Ten years after the creation of the Lincoln Highway, America had a network of over 200 named highways and trails. A number of trail associations and organizations sprang up to promote them, often charging municipalities or businesses along the routes fees or dues. To make some order out of chaos, the national Bureau of Public Roads and Joint Board on Interstate Highways created a numbered U.S. road system to replace the trail designations, with the support of the LHA. For the most part, the Lincoln Highway was designated as U.S. 30, with other parts being U.S. 1, U.S. 40, and U.S. 50.

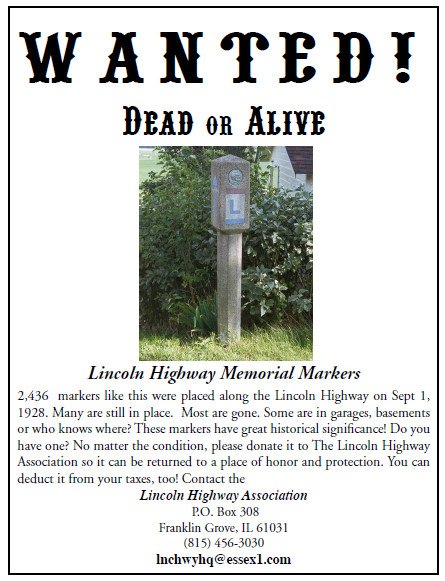

Its work mostly achieved, the LHA ended its promotional activities in 1928 with an official dedication to the memory of Abraham Lincoln on September 1st of that year. At 1:00 p.m. on that day, troops belonging to the Boy Scouts of America placed roughly 2,500 concrete markers at each important crossroad on the route as well as minor crossings, and at other intervals needed to keep drivers on the route. The markers had the Lincoln Highway logo, a blue “L” on a white field, flanked with red and blue stripes, along with a bronze medallion with Abraham Lincoln’s image and dedication, and a directional arrow.

When the LHA disbanded, its complete goal of a paved highway from coast to coast had not yet been reached. Disputes with state officials in Utah caused delays and changes in the route. However, by 1938, all but 42 miles of the Lincoln Highway had been paved and those few remaining miles were then under construction.

As mentioned, the Lincoln Highway Association wasn’t the only private organization to identify, name, and promote a route, highway, or trail. The Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway was conceived by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, in direct response to the creation of the Lincoln Highway.

A southern transcontinental driving route made a lot of sense. Roads were bad enough in the summertime. The Lincoln Highway must have been brutal in the winter.

Still, I’m not convinced that practicality was as important to its founders as creating a distinctively Southern alternative to a highway named after the Great Liberator was. By the early 20th century, the South had risen again, so to speak. Immediately after the Civil War, the South was devastated economically. They couldn’t afford to put up many monuments, statues or even road markers. By 1913, though, the Southern economy had recovered substantially, and the children and grandchildren of Confederate veterans now had the means to commemorate them. It was also a time when the second iteration of the Ku Klux Klan was ascendant with millions of members, and when racist Jim Crow laws, first passed in the 1880s, became entrenched. Under President Woodrow Wilson’s direction, the federal Civil Service and U.S. armed forces instituted systemic racial segregation.

It would be naive to think that in this environment, the decision to name a highway after the head of the Confederacy in response to something called the Lincoln Highway was simply a matter of commemorating history. The Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway was also about putting markers down for the Confederacy, 50 years after Gettysburg.

Carl Fisher’s counterpart in the creation of the JDMH was Mrs. Alexander B. White, president of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Her account of the creation of the Memorial Highway is as follows:

During the Chattanooga Confederate Reunion, May, 1913, while talking to my cousin, T. W. Smith, a Confederate Veteran of Mississippi, highways were mentioned, and I said, “I wish we could have a big, fine highway going all through the South.”

He said, “You can. Get the ‘Daughters’ to start one. The Lincoln Highway is ocean to ocean, you can match that with” and I exclaimed, “Jefferson Davis Highway, ocean to ocean.” All during that summer I considered the feasibility and wisdom of so great an undertaking for the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the probability of my being called on to put my project through.

Later, while I was preparing my report as president-general to the New Orleans convention, United Daughters of the Confederacy, in November, 1913, Mrs. Robert Houston, Mississippi, made this same suggestion to me. This increased my courage and ended my indecision, so into my report went this recommendation: “That the United Daughters of the Confederacy secure for an ocean to ocean highway from Washington to San Diego, through the Southern States, the name of Jefferson Davis National Highway; the same to be beautified and historic places on it suitably and permanently marked.” This recommendation was adopted and the highway project endorsed as a paramount work.

The part about “historic places on it suitably and permanently marked” makes me think that the JDMH was of a piece with the Confederate statuary erected during the same era that is part of our current controversy. It seems to me that at least in part the memorial highway was meant to glorify Davis and the cause of the Confederacy.

That thought is reinforced by two auxiliary routes designated by the UDC. The Lincoln Highway also has auxiliary routes, like the one leading from Detroit to where it meets the main route of the LH at South Bend. The auxiliary routes that the UDC proposed for the JDMH were one from Jefferson Davis’ birthplace at Fairview, Kentucky, south to Beauvoir, Mississippi, where he lived in later years, and a route through Irwinsville, Georgia, following his route at the end of the Civil War before his capture. The Lincoln Highway has no auxiliary route from either President Lincoln’s birthplace in Kentucky nor his home in Springfield, though the highway passes through Illinois.

You can say that the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway was about commemorating history if you choose to, but my mileage does indeed vary. You’ll have to excuse me if I think that bit about following Davis’ route before capture was about glorifying the lost cause.

The JDMH was eventually extended all the way up the Pacific coast by incorporating U.S. 99 when that road was completed in Washington state in 1939.

As with the Lincoln Highway, the JDMH had official markers, with three stripes of red, white and red, and the letters JDH vertically in black. Before WWI, most states had ineffectual highway departments and some of the southern states didn’t even have such agencies, so the UDC was free to promote the JDMH and place its markers on the route. As states’ highway bureaucracies became established, many of the southern states officially designated roads as part of the Davis memorial route, with official monuments.

When the named routes proliferated, inspiring the federal government to establish the U.S. road-numbering system, just as the Lincoln Highway Association did, the UDC lobbied to give the Davis route a singular number across the country. It also appears that they wanted the federal government to officially name the route after the Confederate president, a designation that the Lincoln Highway never received. However, the Bureau of Public Roads repeatedly turned down the request. One of the UDC’s appeals is echoed in today’s debate about Confederate statues, that such monuments are about history. Looking back from today’s unrest over the subject, there’s some irony in that they asserted such commemorations would promote greater national unity.

The Jefferson Davis Highway directors are doing constructive work in every state, and patriotically the women of the United States feel that nothing could tend to the greater unity and understanding of the people than that two transcontinental highways should be named for the two great leaders of the critical period of American history. The Lincoln Highway is, of course, an established fact, and the naming officially of the Jefferson Davis National Highway would be a great progressive step.

The feds were interested in an organized system of roads with numbers, not names. States, however, could call highways whatever they wanted to call them, and the UDC continued to lobby for official designations. They also continued to have designation ceremonies, placing monuments where they could. The UDC really wanted a terminal marker in Washington D.C. but northern congressmen blocked necessary legislative approval. As a compromise, locating the marker in Virginia was proposed. Eventually, in 1946, the Bureau of Public Roads authorized Virginia to erect a 14-ton monument as a terminal marker on the highway, near the Pentagon, on the Virginia side of Washington’s 14th Street Bridge. When it became a traffic hazard due to increased use of the bridge, it was moved in 1964. It’s not clear just where that monument is, if it still exists.

Parts of the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway still carry its state-assigned name, particularly U.S. 1 in Virginia and U.S. 80 in Alabama. In 1965 Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. led a march from Selma to Montgomery on U.S. 80, in support of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, then before Congress. In 1996, under the National Scenic Byways Program that section of road was designated by the U.S. Department of Transportation as an All-American Road and named the Selma-to-Montgomery Scenic Byway. Furthermore, under the National Park Omnibus Act of 1996, the part of the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway that Dr. King marched on was designated a National Historic Trail.

After all of her efforts to get the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway officially named by the federal government, one can only imagine how Mrs. White would have felt about that same government using the road to commemorate Dr. King and the Civil Rights movement.

More complete histories of both highways can be found at the U.S. Dept. of Transportation website:

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/lincoln.cfm

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/jdavis.cfm

Today’s Lincoln Highway Association is a non-profit organization, with chapters in 12 states, dedicated to preserving the Lincoln Highway and its history.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons, Lincoln Highway Associations

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, the original 3D car site.

More by Ronnie Schreiber

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Corey Lewis It's not competitive against others in the class, as my review discussed. https://www.thetruthaboutcars.com/cars/chevrolet/rental-review-the-2023-chevrolet-malibu-last-domestic-midsize-standing-44502760

- Turbo Is Black Magic My wife had one of these back in 06, did a ton of work to it… supercharger, full exhaust, full suspension.. it was a blast to drive even though it was still hilariously slow. Great for drive in nights, open the hatch fold the seats flat and just relax.Also this thing is a great example of how far we have come in crash safety even since just 2005… go look at these old crash tests now and I cringe at what a modern electric tank would do to this thing.

- MaintenanceCosts Whenever the topic of the xB comes up…Me: "The style is fun. The combination of the box shape and the aggressive detailing is very JDM."Wife: "Those are ghetto."Me: "They're smaller than a Corolla outside and have the space of a RAV4 inside."Wife: "Those are ghetto."Me: "They're kind of fun to drive with a stick."Wife: "Those are ghetto."It's one of a few cars (including its fellow box, the Ford Flex) on which we will just never see eye to eye.

- Oberkanone The alternative is a more expensive SUV. Yes, it will be missed.

- Ajla I did like this one.

Comments

Join the conversation

Better to learn from history than bury it and repeat the mistakes.

@Ronnie--Your historical posts are really good. I would like to see more of those posts related to the history of automobiles and the early days of automobiles. Automobiles have changed our lives starting with the Model T. I really believe that this type of history needs to be taught in our schools besides just wars and political figures. Youth would take a much greater interest in history. How the average person lived and how their lives were changed due to major historical events and technological changes such as the industrial revolution and the rise of the automobile industry in America and the effect these events had on the average person.