Ab Jenkins and His Mormon Meteor, Part One

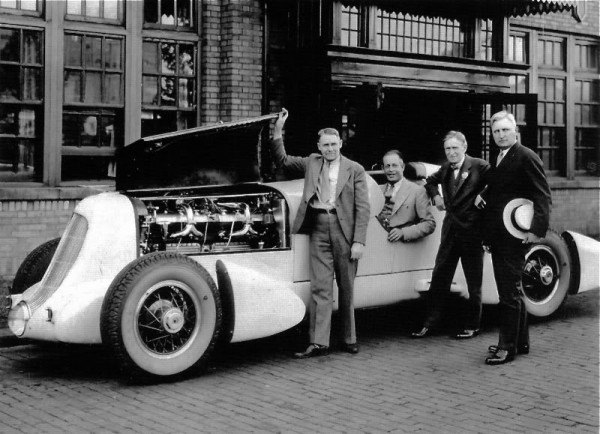

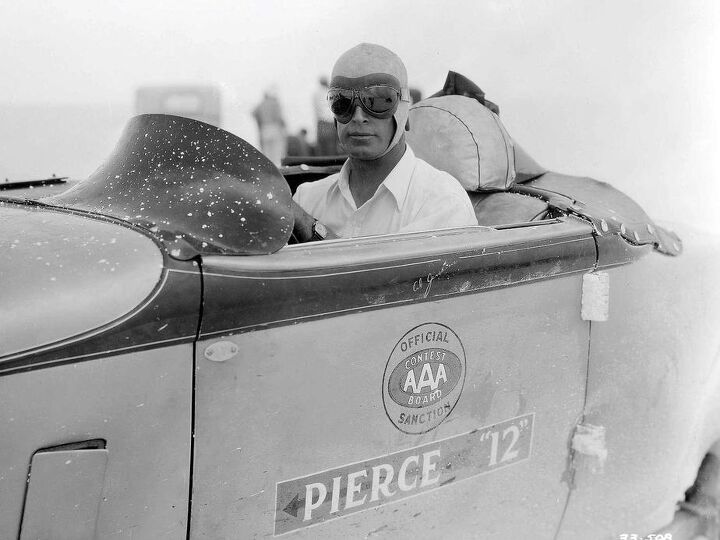

Left to right: Augie Duesenberg, Ab Jenkins (seated in Mormon Meteor), Harvey Firestone, Unknown

Does the name Ab Jenkins mean anything to you? He was once famous as the fastest man on land. What about the name Bonneville? If you’re a car enthusiast, you might associate it with Pontiac, as Bonneville was the nameplate of the now-deceased brand’s flagship sedan. Alternatively, you might think of the Bonneville Salt Flats, where many land-speed records have been set.

As a matter of fact, if you know the name Bonneville in either of those cases, it’s likely due to the efforts of Ab Jenkins, with supporting roles played by Augie Duesenberg and Herb Newport.

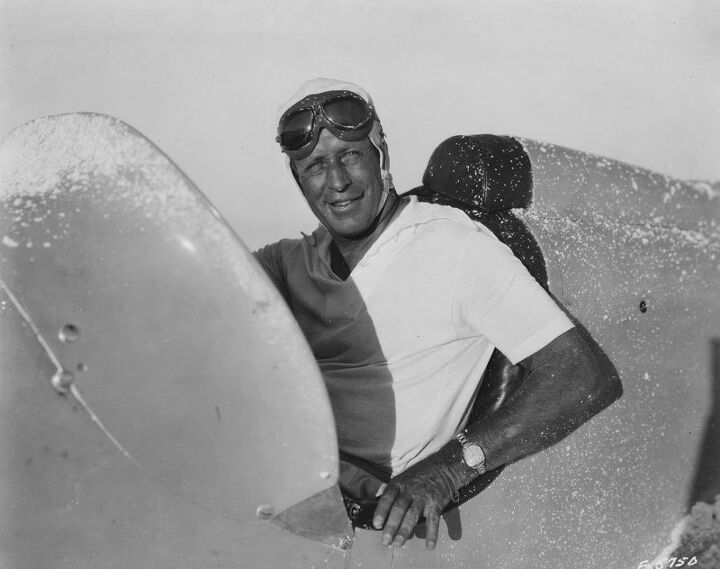

Ab Jenkins

David Abbott “Ab” Jenkins was born in 1883 in Utah to Welsh immigrants. He had the need for speed from his youth, competing in track and field and then racing the then-new “safety bicycle”. Seeking ever more speed, he raced motorcycles in both short track and cross-country events. His day job was working as a builder and general contractor.

His racing exploits garnered Jenkins some local fame around Salt Lake City. A Studebaker dealer there, Thadius Naylor, hired him in 1924 to attempt a run at the speed record for the drive from Salt Lake City to Fish Lake, then held by a rival Studebaker store. Jenkins succeeded and Naylor engaged him to make other long distance records with stock Studebakers, like the run from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles.

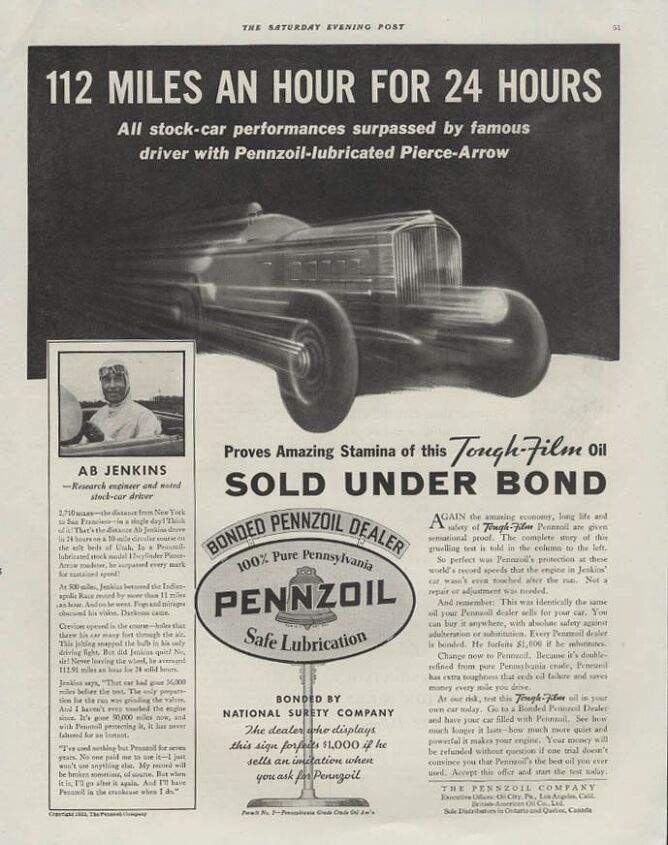

Jenkins’ deal with Naylor for those record attempts specified he’d only get paid if he set a new record. It appears he also had some kind of sponsorship arrangement with Pennzoil. Jenkins was a pioneer in promotional endorsements.

The following year, when a new highway was completed that crossed the Bonneville Salt Flats, Jenkins raced a Union Pacific train across the flats and beat it by over five minutes [Correction: One of our readers has pointed out in the comments that the Union Pacific terminated east of Salt Lake City so the train had to have been from the Southern Pacific or, more likely Western Pacific railroad]. Jenkins realized the long and flat Salt Flats were perfect for land-speed record runs. Until then, the long, sandy beach at Daytona, Florida had been favored for land-speed record attempts. Thinking it would help promote his hometown, Jenkins decided to make Bonneville the world capital of speed, though that didn’t stop him from setting coast-to-coast records for Studebaker.

The late 1920s and early 1930s saw the “cylinder war”, as luxury car makers tried to outdo each other with first 12- then 16-cylinder engines. Pierce-Arrow wanted to introduce their own V-12, but company engineers were unable to get any more horsepower out of the twelve than they were generating with Pierce-Arrow’s eight. By then, 1931, Jenkins’ record runs had gotten him noticed beyond Utah and Pierce-Arrow hired him as a consultant. Sources say his suggestions helped company engineers raise the V-12’s output by 45 horsepower.

He then suggested a 24-hour endurance record run on the salt flats, promising Pierce-Arrow executives he would cover 2,400 miles in that time, averaging at least 100 mph. The people at Pierce-Arrow were skeptical, including Jenkins’ friend, Roy Faulkner, the sales manager for the company. So skeptical, in fact, that Faulkner supplied Jenkins with a used Pierce with over 33,000 miles on the odometer.

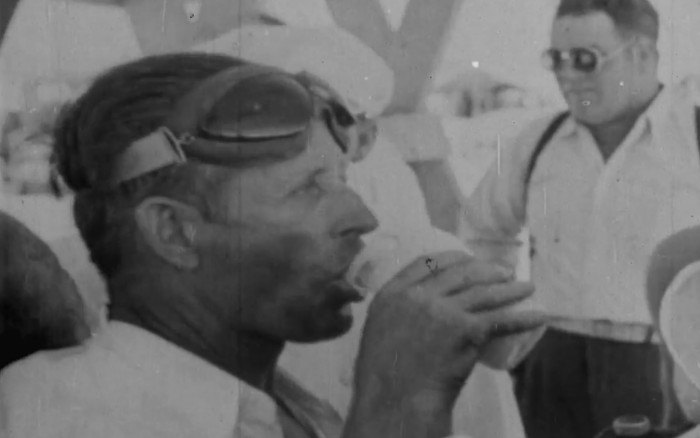

Jenkins had a 10 mile circular track laid out and smoothed on the salt flats. He removed the fenders and windshield from the car to reduce drag, covered his face in grease for protection from the sun, put on some goggles to protect his eyes, and set off on the endurance run. He ended up covering over 2,700 miles by himself, only stopping for gas every two hours. Making the feat even more impressive was the fact that Jenkins was a devout Mormon, so he didn’t even use coffee to help stay awake. Ab was concerned about his clean cut image, literally. When photos of the event started appearing in newspapers, he was upset at how he looked unshaven when he got out of the car.

Though the run was a great publicity stunt, it didn’t result in an official record. The next year, Jenkins arragned for observers from the Automobile Association of America. When the scheduled day arrived, conditions were bad with rain and wind, but Jenkins managed to drive 3,000 miles in 25 and a half hours, maintaining an average speed of 117.77 mph.

To make sure he looked good when he finished this time, a crew member made sure there was a safety razor and tube of Barbasol shaving cream in the car. As he completed his final laps on the salt flats course at speeds up to 125 mph, Jenkins gave himself a shave.

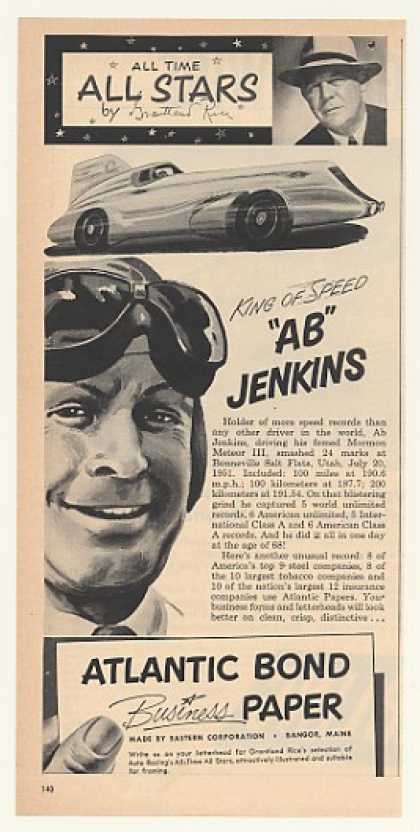

Ab Jenkins was very successful at getting endorsement deals and sponsorships, from spark plugs to motor oil to business paper. The cynic in me thinks there might have been some product-placement type promotional deal involved with Barbasol, but Jenkins likely would have been open about it if that was the case. He was said to be a man of integrity, which was highlighted by the sponsorship deal he made to get tires for his next record run (the cynic in me will simply point out that he did go into politics for a while, later serving as Salt Lake City’s mayor).

His tire supplier for the 1932 record run was Firestone. However, Jenkins had apparently incurred some fines from the AAA relating to the 1932 run and not only did Firestone’s racing representative, Waldo Stein, refuse to pay for those fines, the company didn’t want to cover the AAA’s sanctioning fees for a proposed attempt to set a new record in 1933. Jenkins’ earlier cars had stock, albeit stripped down, bodies. His 1933 car, the Pierce 12 Special, would have a custom streamlined body.

Ab turned to the B.F. Goodrich Company, whose tires were not yet associated with speed or endurance events, and they happily agreed to sponsor the now-famous driver. They issued him a check for $10,000. When Harvey Firestone got wind of that deal, he told Stein to get Jenkins back on Firestone tires, no matter the cost. Essentially presented with a blank check, Jenkins was true to his word, wouldn’t break his one-year contract with Goodrich, and indeed set a new record on that company’s tires.

Jenkins was successful at setting records and generating publicity for himself and his sponsors, and his work to promote the Bonneville Salt Flats was beginning to yield dividends. Not only were the salt flats ideal for high speed, the cars used in the attempts were getting too fast for alternatives like the narrow track at Montlhéry, France or the sandy beach at Daytona. Bonneville was wide, long and flat.

Pierce 12 Special

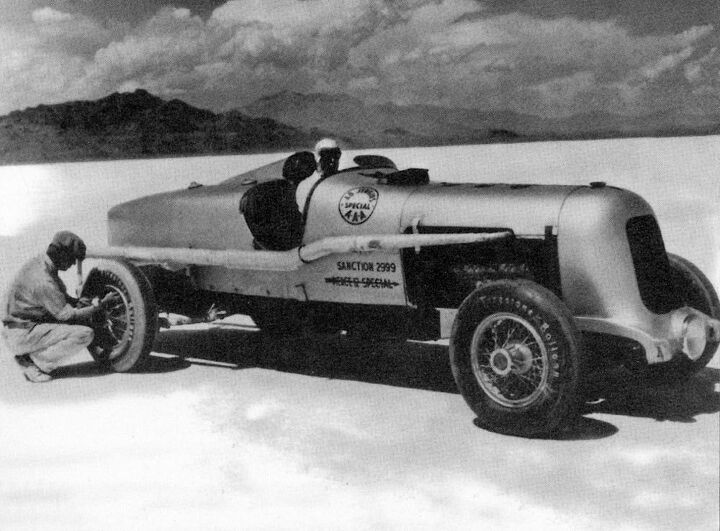

A great sportsman, Jenkins was happy when John Cobb of England decided to challenge Ab’s record and do it at Bonneville in July of 1935. Jenkins not only provided Cobb’s team with tents and pit equipment, he let Cobb take his place in the running schedule. Cobb repaid that generosity by eclipsing Jenkins’ 100 mile and 24 hour records. Jenkins was happy for Cobb and for Utah. The validation of Bonneville as the world capital for speed more than made up for his temporarily losing those records. Besides, he was already in the process of staging an assault on the record with a new car built by Duesenberg

The Pierce-Arrow V-12 wasn’t slow, but by the mid-1930s the Duesenberg brothers had already added a supercharger to the magnificent Model J engine, boosting its output to 320 horsepower, making it the most powerful American car of its day. Other technical advances, like hydraulic brakes, made the Model J chassis ideal as the basis for a speed record car.

We’ll look at the car that became the Mormon Meteor in Part 2.

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, a realistic perspective on cars & car culture and the original 3D car site. If you found this post worthwhile, you can get a parallax view at Cars In Depth. If the 3D thing freaks you out, don’t worry, all the photo and video players in use at the site have mono options. Thanks for reading – RJS

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, the original 3D car site.

More by Ronnie Schreiber

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- SPPPP I am actually a pretty big Alfa fan ... and that is why I hate this car.

- SCE to AUX They're spending billions on this venture, so I hope so.Investing during a lull in the EV market seems like a smart move - "buy low, sell high" and all that.Key for Honda will be achieving high efficiency in its EVs, something not everybody can do.

- ChristianWimmer It might be overpriced for most, but probably not for the affluent city-dwellers who these are targeted at - we have tons of them in Munich where I live so I “get it”. I just think these look so terribly cheap and weird from a design POV.

- NotMyCircusNotMyMonkeys so many people here fellating musks fat sack, or hodling the baggies for TSLA. which are you?

- Kwik_Shift_Pro4X Canadians are able to win?

Comments

Join the conversation

This movie from 2011 is all about the Meteor and I enjoyed it much. "Boys of Bonneville — Racing on a Ribbon of Salt."

There's always one in every thread... but I can't resist it. Great article but Mr. Jenkins didn't race a Union Pacific steam locomotive since the Union Pacific terminated at Ogden, east of the lake. Both the Southern Pacific and Western Pacific cross west of Salt Lake City. Looking at makes of the Bonneville International raceway, I'd guess it was the Western Pacific. The WP was bought by the UP in the 1980's, the race could occur today as noted.