1965 Impala Hell Project, Part 12: Next Stop, Atlanta!

After the Nixon-head-hood-ornamented Impala’s pilgrimage to the birthplace of Richard Nixon in the spring of 1994, I left Oakland and moved across the Bay to an apartment on Valencia Street in San Francisco’s Mission District, home of the best burritos in the world. Little did I know that it wouldn’t be long before I’d be packing all my possessions into the Impala and blasting 2,500 miles to the southeast.

By early 1995, I’d settled into a routine of office-temp work in the Financial District, cheap burritos for dinner ( El Toro and El Farolito were— and still are— my favorites), and evening drives over Twin Peaks to see a girlfriend who lived about 50 yards from the Pacific Ocean (this was only a five-mile trip on paper, but a grueling 40-minute/thousand-stop-sign slog by automobile; San Francisco makes blocks seem like miles). I used BART to get to work, because only Daddy Warbucks can afford to park in downtown SF, so the Impala spent its days parked near the corner of Valencia and 24th. In those days, back when this part of the Mission was cheap and not yet fully hipsterized, any car parked in my neighborhood had about a 100% chance (per week) of being broken into, vandalized, or bashed into by a drunk in an Electra 225 running three space-saver spares. Actually, the gentrification of the Mission hasn’t changed a damn thing; the cars are nicer today, but they still get just as trashed on the street.

But my car didn’t get touched. Even the most desperate crackhead could sense that it wasn’t worth smashing a side window with a chunk of spark-plug porcelain in order to rummage for 16¢ in the glovebox. Parallel parkers with 11 sloe gin fizzes under their belts exercised unprecedented caution when squeezing 18 feet of car into an 18.5-foot space bounded by my car. It’s possible that my car got key-striped or tagged, but I wouldn’t have noticed. I’d remove my 20-pound pull-out octophonic sound-system rig, leave the glovebox door open to show its emptiness, and the car would be left alone.

In short, my Impala turned out to be not only an ideal long-distance road-trip machine but a perfect urban survivor as well. About the only drawback was its size; the big Chevrolets of this era have a surprisingly tight turning radius, but in San Francisco you’ll find a lot of spaces that only a CRX or smaller can squeeze into.

Everything was going fine. I’d settled into a decent-paying long-term temp gig with a junk-mail-mill of an environmental charity I won’t name because they’d probably sue me out of existence, removing the names of dead donors from the mailing list and answering angry letters from live donors upset about said charity taking money from Pollutco, Inc. (by the way, I learned that gluing a junk-mailer’s Business Reply Envelope to a chunk of 2×4 or stuffing the envelope with lead plates from a car battery totally works, or at least it worked in 1995; I was the one who threw out such objects every day). As winter became spring, my coast-dwelling girlfriend’s graduation from San Francisco State loomed. In spite of my warnings about the perils of academia, she decided that she really wanted to pursue a PhD in American History. Emory University near Atlanta offered her a fat fellowship— in essence a free-ride tuition deal with a juicy stipend check on top— and it was an offer she didn’t refuse.

So, the decision had to be made: dump her or move to Georgia with her. All I knew about Georgia came from obsessive reading of Flannery O’Connor’s work, supplemented by Eric Foner’s no-punches-pulled history of Reconstruction, and I was uneasy (to put it mildly) about moving there. This sort of dilemma calls for a road trip!

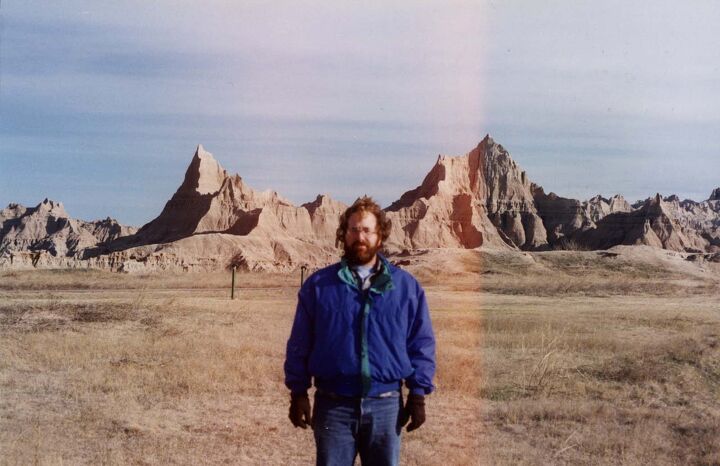

My friend— and future brother-in-law— Jim was itching to drive a circuit of the country in his much-traveled ’88 Toyota pickup, and I figured we could visit Atlanta on the way and see if I could stand living in the place. I put together a special mix tape, we loaded up the camping equipment, and we hit the road.

Our route was a circuit around the perimeter of the country: up to Idaho, across the Upper Midwest to New York City, down the Atlantic coast and then west across the Deep South, Texas, and the Southwest. We’d sleep in campgrounds or on friends’ couches at various cities along the way, cook our own meals, and do the whole trip in 22 days. It was a blast, but The Man kept sweating us (I’m pretty sure the Toyota’s California plates and Grateful Dead stickers contributed to John Law’s low opinion of the vehicle). The South Dakota Highway Patrol pulled us over outside Rapid City, put us in the back seat of the Crown Victoria, and dumped the contents of the truck onto the shoulder in a quest for nonexistent drugs and guns (“There’s a regular traffic in stolen firearms from California to Minneapolis,” one cop grated, “and you boys fit the description perfectly”). We got hassled at rest stops, where the cops were doing random warrantless searches of vehicles with dogs, and we happened to be entering Atlanta during Freaknik, a gathering of black college students that had every law-enforcement officer in Georgia roaring about the highways in a heavily-armed frenzy… and then some nutjob mass murderer went and blew up the Federal Building when we were a few hours east of Oklahoma City. We heard reports on the radio that “two men in a blue pickup” were seen fleeing the scene and we figured we’d be arrested and/or lynched any minute. To us, the best move seemed to be to continue to drive toward OKC, because that’s the one direction the perps probably wouldn’t be going. We were spared a nightmarish experience with law enforcement and/or vigilantes when McVeigh and his beater ’77 Marquis made the world’s lamest getaway, and we passed through Oklahoma without incident (other than being freaked out by the horror that had taken place).

The upshot of all this was that I figured Atlanta looked interesting as a place to live, and that cross-country driving in a sketchy-looking vehicle with California plates is extremely stressful. What the hell, I thought, it will be an adventure. We’d leave San Francisco in August.

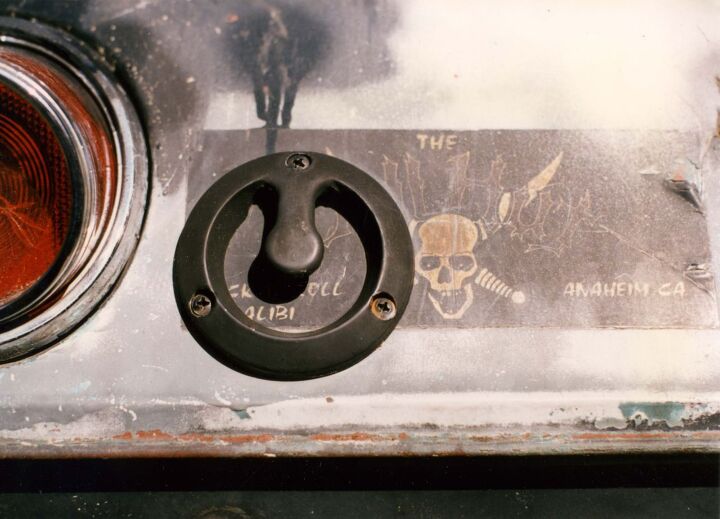

I wasn’t sure how well we’d be able to fit all our stuff inside the Impala (even after ruthless culling of our respective book collections— including most of my first-edition Philip K. Dick paperbacks— we still had hundreds of pounds of the things), so I screwed some junkyard-sourced tie-downs on the trunk lid and rear quarters. That way we’d be able to travel in true Joad Family style, with crates of squawking chickens and kitchen utensils tied to the outside of the car, though we’d be leaving California instead of fleeing to it. Too bad about the Doll Hut sticker, but I’d get a new one during my next Orange County trip… whenever that might be.

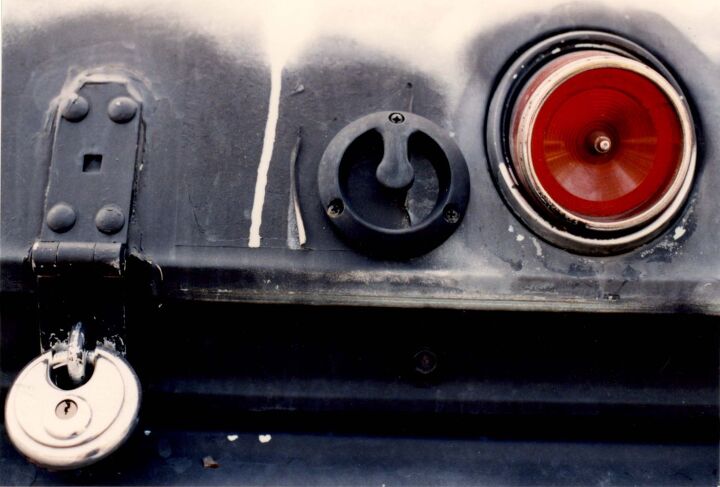

It appeared that the only way to haul our bicycles— which were worth more than the car— would be on the trunk lid, so I devised this trunk-mounted bike rack to keep them secure from motel-parking-lot thieves. We’d lock the bikes to the bar— which was a galvanized steel plumbing nipple with a few hacksaw-jamming 283 pushrods inside— using our San Francisco-grade U-locks. This bar now lives on as the grab handle of my Junkyard Boogaloo Boombox, which provides tunes when I’m working in the garage. As it turned out, the disassembled bikes fit inside the car, stacked on all the boxes in the back seat, so the trunk bar served only to confuse onlookers.

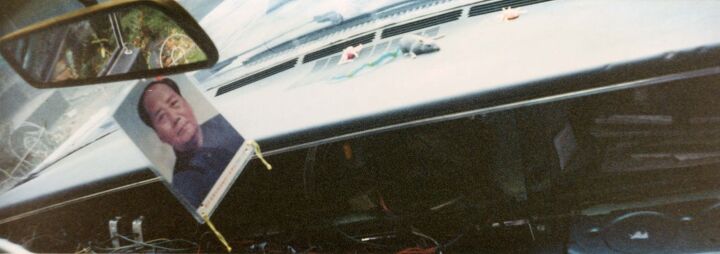

I felt confident that no thief would be able to figure out the bewildering array of dash switches and hot-wire the car, but what about battery thieves? Cutting a few bars of grille out of the way and attaching a chain to a carriage bolt through the hood solved that problem.

And I didn’t want the same motel-parking-lot thieves who’d be frustrated by the locked-down bicycles to have a shot at the valuables in the trunk, so I added this hasp and bolt-cutter-proof padlock. I thought about adding hasps to the doors as well, but decided we’d just keep the not-worth-stealing boxes of books in the back seat and put everything else in the trunk. Just as well, because I wouldn’t have wanted my car to look like this Cadillac.

The plan was to drive I-80 through Nevada and into Utah, then turn right at Salt Lake City to visit some relatives in southeastern Utah. From there, we’d take I-70 east, visit some more relatives in Kentucky, then head south to Atlanta. Driving a 30-year-old car loaded with a half-ton or so of cargo across the desert in the height of summer seemed like a bit of a gamble, so I invested a couple hundred bucks in a new Modine radiator (the old one had a JB Weld patch about 4″ wide, from a baseball-sized rock that had bounced off a gravel truck and put a huge hole in the radiator a few years earlier, and I didn’t quite trust the patch) and added a junkyard transmission cooler. All my tools would be on board, and I figured I’d have no problems finding parts in the event of a mechanical failure. Pack it up, move it out!

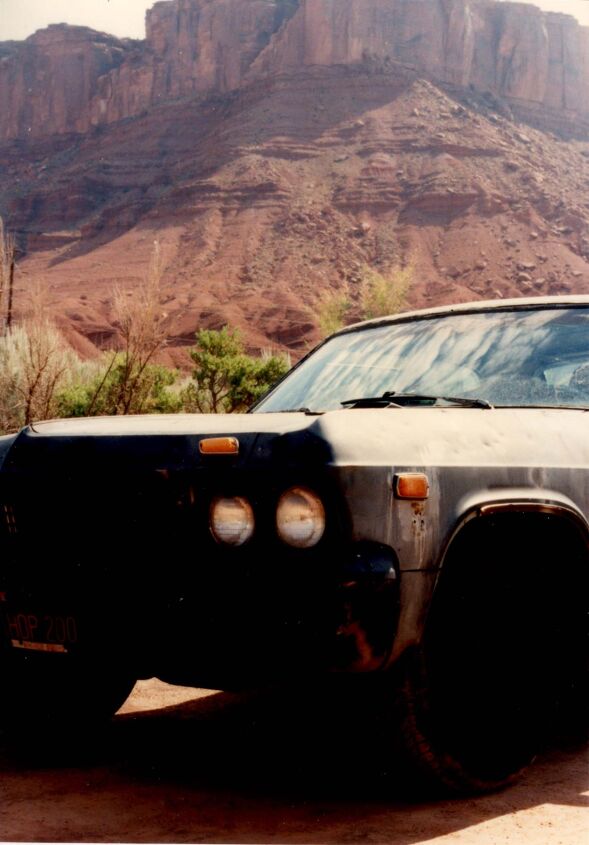

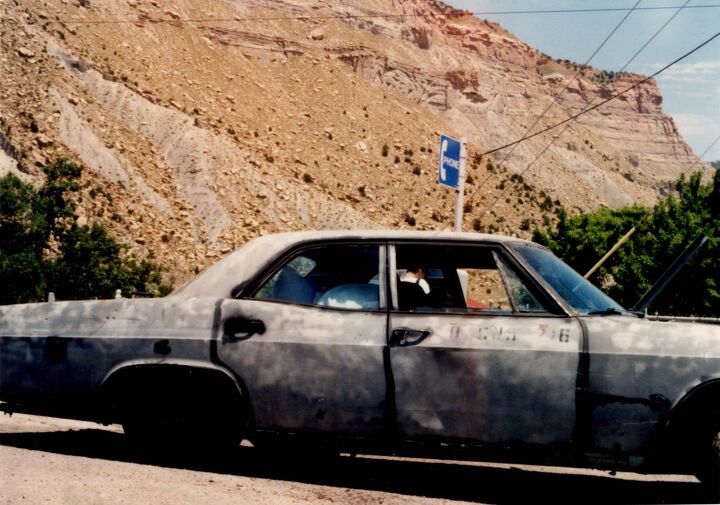

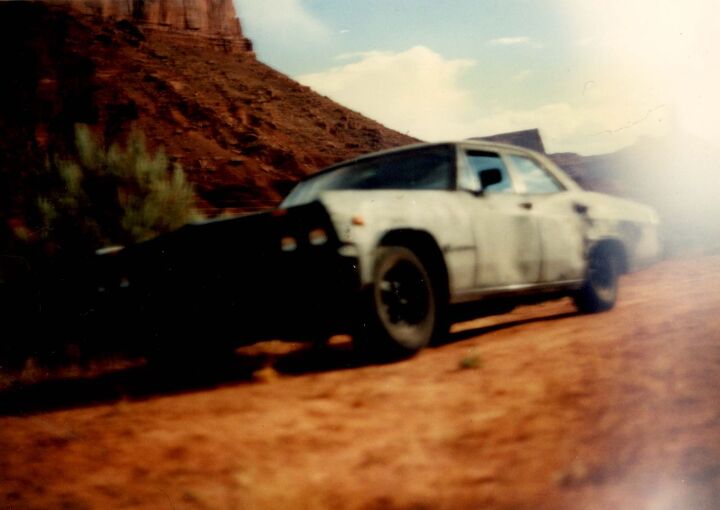

At this point, we run into the limitations of the pre-digital-camera era again; this cross-country drive was so hectic and stressful that I managed to take only a handful of photographs, all on a point-and-shoot camera loaded with color print film (yes, the old days sucked in so many ways). The car made it to Moab just fine, with the only incident being a busted tailpipe caused by the car bottoming out in a gas-station entrance. A little beer-can-and-hoseclamp work fixed the tailpipe, and the car kept rolling. Note how low the rear of the loaded-down car is in this photo; I considered adding some JC Whitney overload springs before we left, but ran out of preparation time.

The mercury hit 115 degrees on the day we left Utah, and it stayed above 100 for most of the drive to Kentucky. We were sweating like crazy with no air conditioning (rolling all the windows down and spraying our faces with a plant-mister bottle helped some), but the engine never came close to overheating.

While the Impala got a lot of double-takes from the Smokeys, we didn’t get pulled over even once. My assumption is that the car was just so shockingly blatant in its California wretchedness that the law figured “Damn! Anybody this obvious couldn’t be doing anything illegal.” Such a relief— I’d counted on having to unload everything for police searching on a scorching road shoulder while 18-wheelers blared by, at least a couple of times.

The stop at the Kentucky in-laws’ place was a nice break, and then we turned south. Tennessee was my first real experience with the Southern flavor of surrealism. We started seeing stuff like this more and more frequently the further south we went. Tin Can Baby… Test Tube Baby… Stick Baby… Just Say No!

I wasn’t one of those Yankees (are Californians considered true Yankees?) who based his entire conception of the South on “Deliverance” and Lynyrd Skynyrd songs, but coastal California is full of ex-Southerners who fled the place and then scare the shit out of Californians with endless horror stories about their homeland. I was nervous. So when I stepped out of our room at the Stonewall Jackson Motor Lodge in Murfreesboro, Tennessee and found a couple of overalls-with-no-shirts-wearin’, tobacco-chewin’, toothless, gristly, possum-innards-eatin’ cronies leaning on the Impala’s fender and drinking tall cans of Colt .45 at 8:30 in the morning, well, I didn’t know what to expect. The tall skinny one looked at the short fat one, took a swig of Colt, then looked at me. “You gwine pint thet car?” he asked. Why, no, I wasn’t. “I like the way it looks right now,” I replied. That seemed to satisfy them, or at least that’s how I interpreted their nods.

Atlanta was a very weird place in the summer of 1995. The Olympics were coming the next year, and the whole state was wild-eyed with excitement about Atlanta emerging from the games as a “World Class City,” a destination for international dealmakers and tourists from all corners of the globe. The Olympics would change everything!

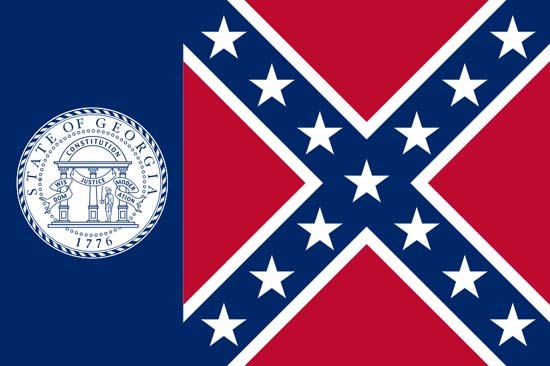

At the same time, the screaming matches over the state flag— which had received its Confederate-ization treatment in 1956, as a response to the Civil Rights movement— were freakin’ deafening, what with the international attention it would be receiving as soon as all those Olympic visitors showed up. Atlanta’s unofficial slogan, “The City Too Busy To Hate,” seemed pretty defensive, and also a dig at archrival Birmingham, which Atlantans sneered at as “The City of Lazy No-Goodniks That Always Have Time To Hate.” This Olympics-fueled civic pride translated into landlords believing they’d be rich once the athletes showed up (apparently believing that high-buck renters would start showing up six months before the Games), and it was a real challenge finding a place to live at a price we could afford.

After a week or two of living at a crackhead motel, however, we found an apartment just off Ponce de Leon (that’s pronounced “Ponse duh LEE-on”) in Decatur, walking distance from Emory.

I roamed around exploring the area and looking for jobs, and found that a non-air-conditioned car in dark primer paint was not ideal under conditions of hundred-degree heat and 98% humidity, especially when wearing an interview suit.

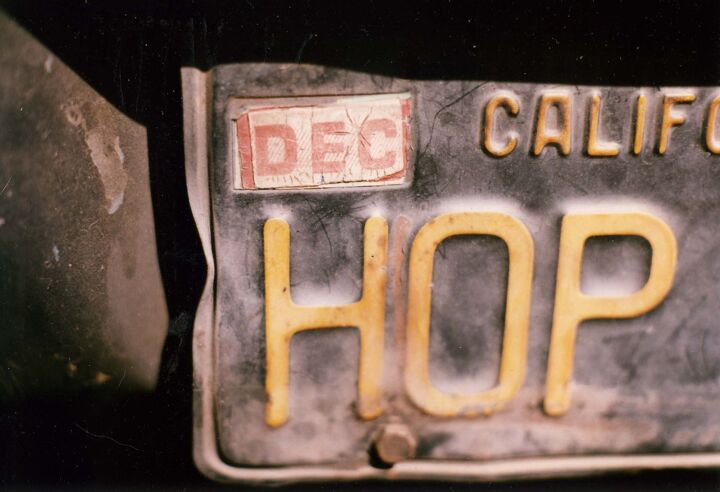

It felt cool getting some Georgia plates for my ride— the peach color looked great in contrast with the grim grayscale look of the car— and I enjoyed eating biscuits and gravy in old-time Southern diners full of chain-smoking 100-year-olds. Other than the interior temperature, the Impala was well suited to its new home.

We took a brief trip south to visit a relative near Talahassee and a turn down the wrong dirt road led to a long Heart of Darkness-style drive on muddy trails in the jungle. I never did find Mistah Kurtz, but I did find the long-sought Refrigerator Graveyard, a swamp where thousands of dying refrigerators and other large appliances crawl off to die. The Impala turned out to be an excellent dirt-road machine, even with its open differential. I wish I had more Heart of Darkness Impala photos from the jungle expedition, but this is the only shot that came out.

I found plenty of interesting cars during my travels, including this “ran when parked” Cad, and Georgia junkyards were great (more on them later).

I also found plenty of historically interesting stuff as I roamed in the Impala. Here’s Martin Luther King’s church, located a few miles from my apartment in Decatur. General Sherman’s headquarters during his stay in Atlanta— or, rather, what was left of Atlanta after he got through with it— was also near my place, and the locals had allowed it to become completely buried under tons of kudzu.

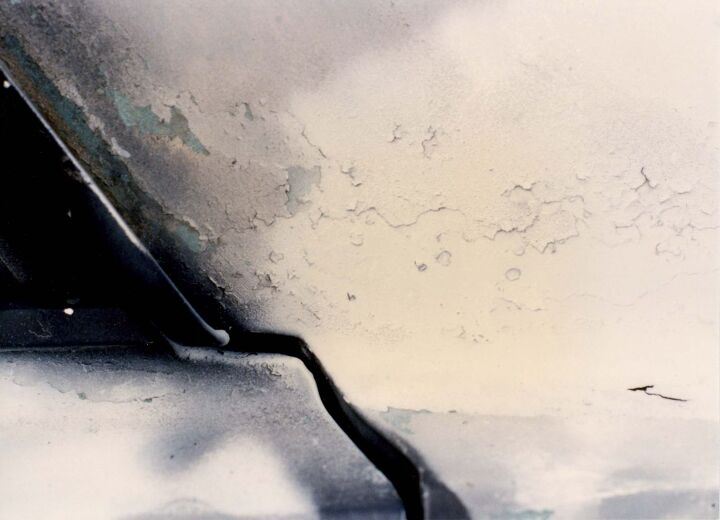

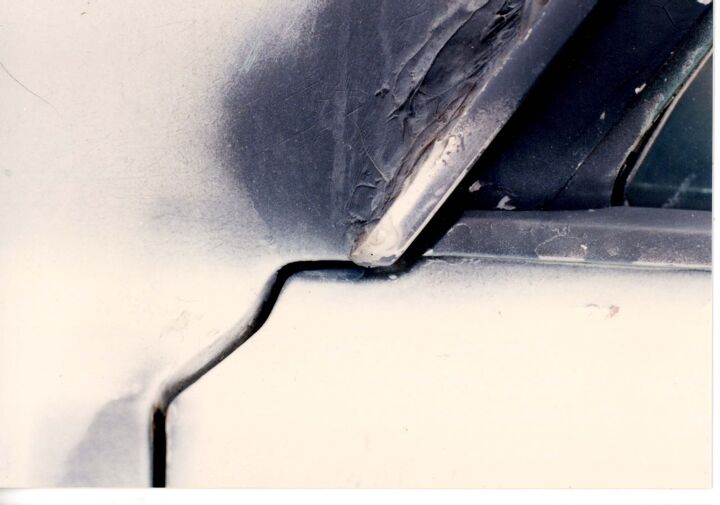

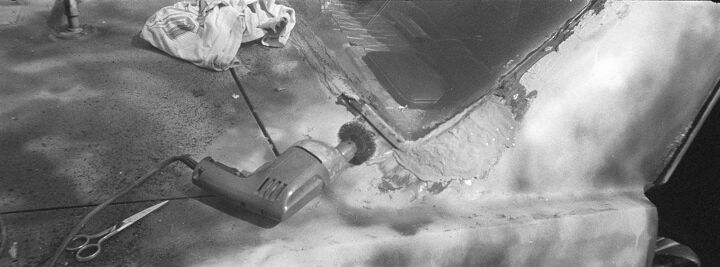

The Impala’s leaky rear window (a GM trademark for decades), which I thought I’d fixed forever with silicone and roof cement, became a real problem during Atlanta’s torrential summer-afternoon thunderstorms. The right rear corner was the main trouble spot, with California-style rust-through where water had sat for months at a time during 30 years of West Coast winters. I decided to get serious, ground away all the rot with a wire wheel, and applied large quantities of JB Weld to the problem spot. It worked perfectly.

My employment search turned up nothing but more office-temp work for the first month or so of Georgia residence, but then I stumbled into the perfect job. Next up, Mad Max at Year One!

Introduction • Part 1 • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4 • Part 5 • Part 6 • Part 7 • Part 8 • Part 9 • Part 10 • Part 11 • Part 12 • Part 13

Murilee Martin is the pen name of Phil Greden, a writer who has lived in Minnesota, California, Georgia and (now) Colorado. He has toiled at copywriting, technical writing, junkmail writing, fiction writing and now automotive writing. He has owned many terrible vehicles and some good ones. He spends a great deal of time in self-service junkyards. These days, he writes for publications including Autoweek, Autoblog, Hagerty, The Truth About Cars and Capital One.

More by Murilee Martin

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Lorenzo People don't want EVs, they want inexpensive vehicles. EVs are not that. To paraphrase the philosopher Yogi Berra: If people don't wanna buy 'em, how you gonna stop 'em?

- Ras815 Ok, you weren't kidding. That rear pillar window trick is freakin' awesome. Even in 2024.

- Probert Captions, pleeeeeeze.

- ToolGuy Companies that don't have plans in place for significant EV capacity by this timeframe (2028) are going to be left behind.

- Tassos Isn't this just a Golf Wagon with better styling and interior?I still cannot get used to the fact how worthless the $ has become compared to even 8 years ago, when I was able to buy far superior and more powerful cars than this little POS for.... 1/3rd less, both from a dealer, as good as new, and with free warranties. Oh, and they were not 15 year olds like this geezer, but 8 and 9 year olds instead.

Comments

Join the conversation

Wonderful read and great photos. Was the razor-sharp steering of the big Impala somewhat compromised by the tail-heavy road stance?

JB weld fixes any problem! Loving all of the parts so far still dieing for more