1965 Impala Hell Project Part 4: Saddam Chooses My New Engine

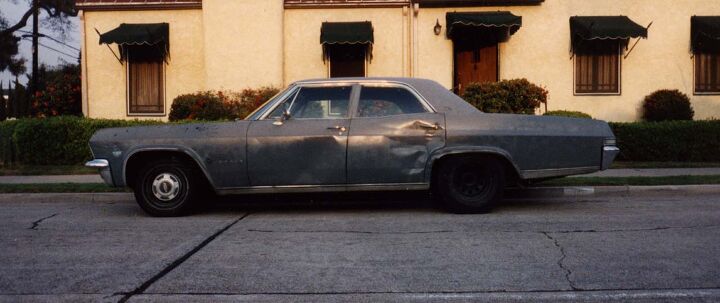

When I bought my Impala, I knew that its 300,000-mile 283 engine wasn’t long for the world, what with the near-nonexistent oil pressure, clouds of oil smoke under acceleration and deceleration, and fixin’-to-toss-a-rod sound effects. Still, due to thin-wallet limitations, I was determined to squeeze one last year of property-value-lowering 283 driving before obtaining a junkyard replacement engine. This plan went well until I decided to seek chemical assistance for the oil-burning problem.

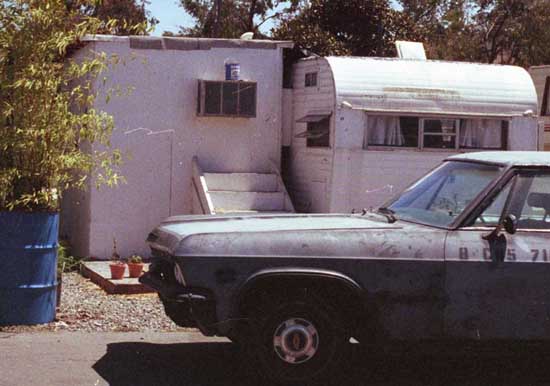

By the summer of 1990, I’d already graduated from college but planned on staying in UCI’s students-only trailer park until forced to leave its 75-bucks-a-month utopia by the beginning of the fall quarter. A summer of leisure and Murilee Arraiac gigs before being dumped into the no-jobs-nohow grinder of the (laughably mild by current recession standards) early 1990s recession.

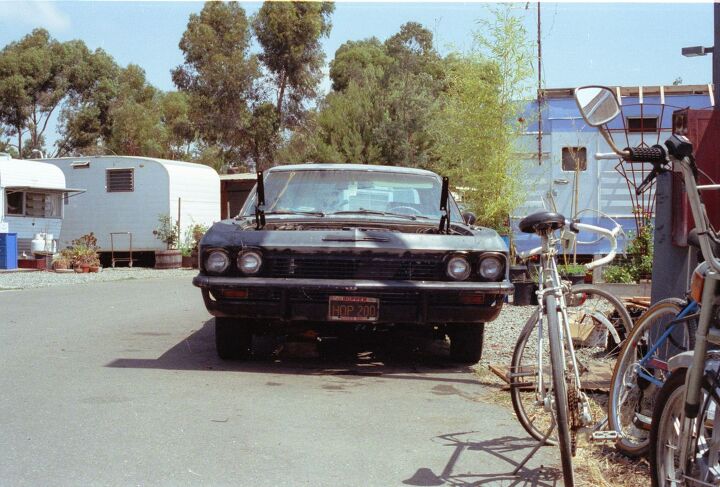

I’d already found that I loved driving my ’65. Even in its worn-out state, it was comfortable and handled quite well. The four-wheel, single-circuit drum brakes were scary, but they were good enough for our forefathers.

The smokescreen behind the car when gunning it up a freeway onramp was fairly alarming; I could see behind the car, sort of, but it’s no fun driving one of the smokiest cars in already-smoggy Southern California. The 283’s thirst for oil was a bit of a problem, too: a quart every 100 miles. That meant that the car drank about three quarts of oil per tank of fuel. A mechanic friend suggested that I try some of that magical “engine rebuild in a can” engine-flush treatment. “The theory is that the stuff will dissolve the crud on the oil rings and let them expand to fit the cylinder bores,” he told me. “Most of the time it doesn’t do much, but it can’t hurt to try.” I pictured “Pop,” the crusty Guadalcanal vet teaching Intro To Auto Shop at Anaheim High in 1981, brandishing a can of Groundwater Contamination Plus™ Engine Flush at the students, including my friend, and rasping in his 4-packs-of-Pall-Malls-a-day voice: “If the Studebaker is burnin’ oil, why, ya just dump a can of this in her! Works every goddamn time, I tell ya!”

Well, “Pop” was full of shit. I added the engine flush to the oil, ran the engine for a while, then changed the oil. Disaster! It turned out that my engine’s rings were made of crud, and dissolving the stuff turned my engine from a medium-grade oil burner that could still be driven to an apocalyptic smoke machine that burned a quart of oil per mile. The billows of blue smoke were so bad under acceleration that cars behind the Impala had to pull over and stop due to lack of visibility. My girlfriend at the time lived a couple miles away, and rather than walk ( unthinkable in Southern California) I took to gunning the car up to about 90 on University Drive, relying on the half-mile of completely opaque smoke to render me invisible to John Law, then cutting the engine and coasting the rest of the way to her place. Clearly, this was not a viable daily-driver situation, so I was forced to dig into my meager funds and push my engine-swap timeline forward.

In 1990, you could buy gas for just over a buck per gallon, so my plan was to find a junked GMC truck, pull its 454 big-block engine, throw a low-budget rings-and-bearings (plus headers and lumpy cam) rebuild at it, and drop it into the Impala’s big-block-ready engine compartment. This would be in keeping with the Hillbilly Street Racer facet of my American Automotive Archetypes Trinity concept, and if it got single-digit fuel economy, so what? Then, just days before I was to start scouring junkyards for a 454, Saddam’s armies rolled into Kuwait. On August 2, 1990, I was sure that the country was about to experience a repeat of the gas lines and surging prices of the ’79 Iranian Revolution energy crisis, and so I downgraded my engine plans from big-block to small-block. I’d make do with a less thirsty 350 until the inevitable couple of years of gas-station madness passed by (as it turned out, the spike in pump prices caused by Gulf War I wasn’t as bad as I’d expected, but all the war scenarios I imagined involved Saudi Arabia’s oil fields getting destroyed, which didn’t happen).

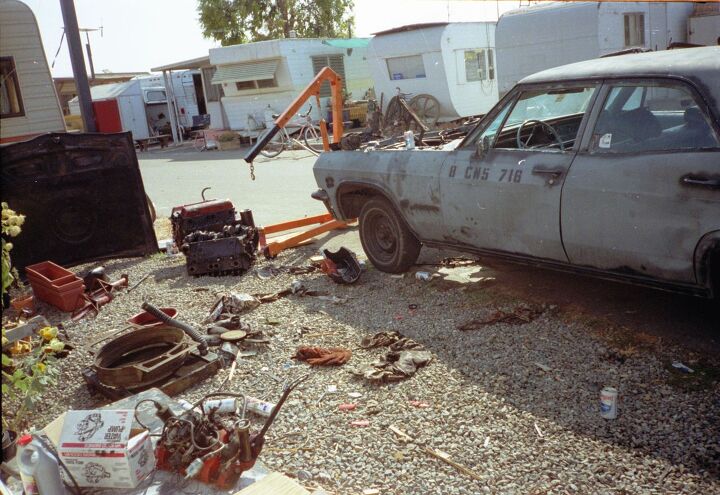

The Man had discovered that I was no longer a UCI student, having finally gotten around to cross-referencing the graduation list with the student-housing list, and— like Saddam and his tanks— was about to crush me and my trailer home. This meant that I didn’t have time to do a junkyard-engine-rebuild project, so I scrounged up a few hundred bucks and bought a long-block 350 from one of the dozens of cheapo rebuild shops in Los Angeles; a friend with an Econoline wanted a 302 long block as well, so we found a place with a discount for purchases of two or more engines. Smog heads and two-bolt mains, but I knew it would keep me mobile until gas prices dropped down to big-block levels; replacing the two-speed Powerglide transmission with a three-speed Turbo-Hydramatic 350 would give the car an off-the-line performance boost that would feel like another 100 horses, anyway.

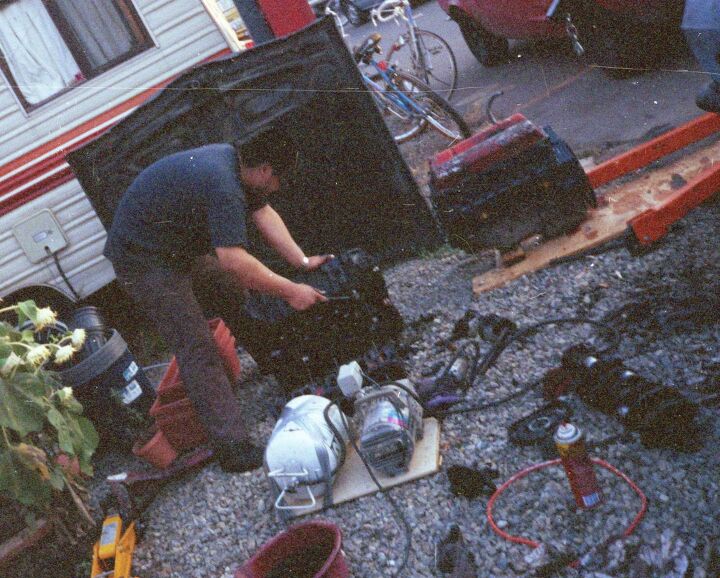

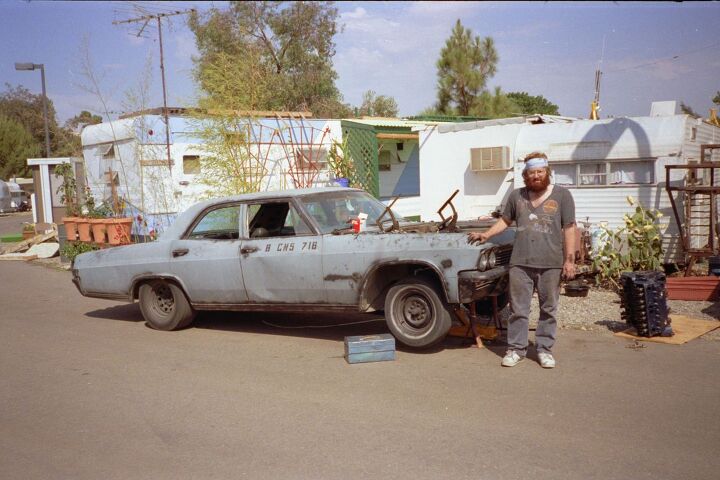

Here we are, a beautiful summer morning behind the Orange Curtain, and I’m violating just about every regulation, restriction, and bylaw in the Irvine Master Plan. Trailer, primered-out Detroit barge on jackstands, engine sitting in the gravel. It’s good to be on California state property and out of reach of The Plan.

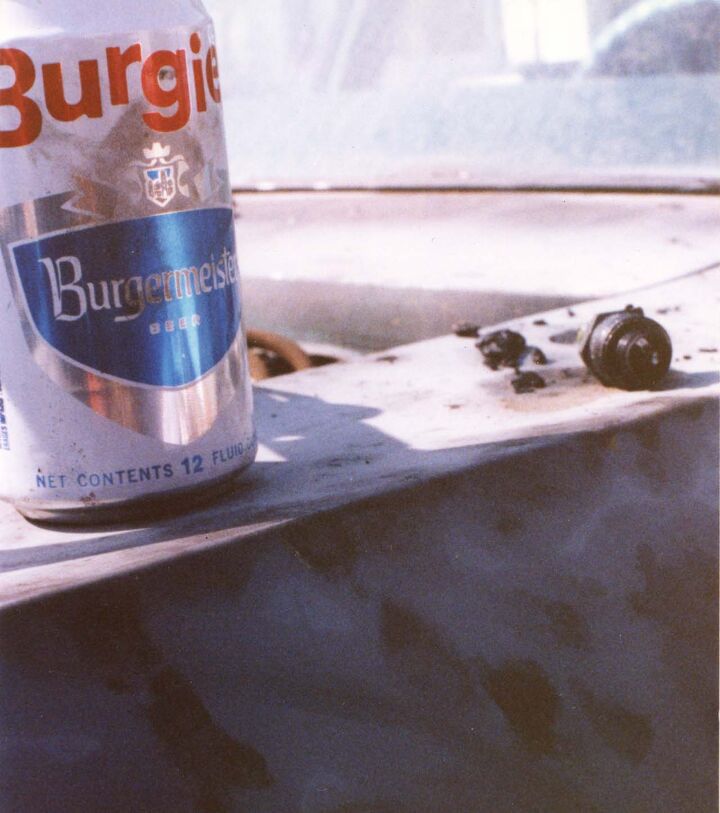

There are some things I remember fondly about my early 20s, but being limited to terrible beer by lack of funds isn’t one of them. Still, there’s something right about a cold Burgie on a hot engine-swapping Southern California day.

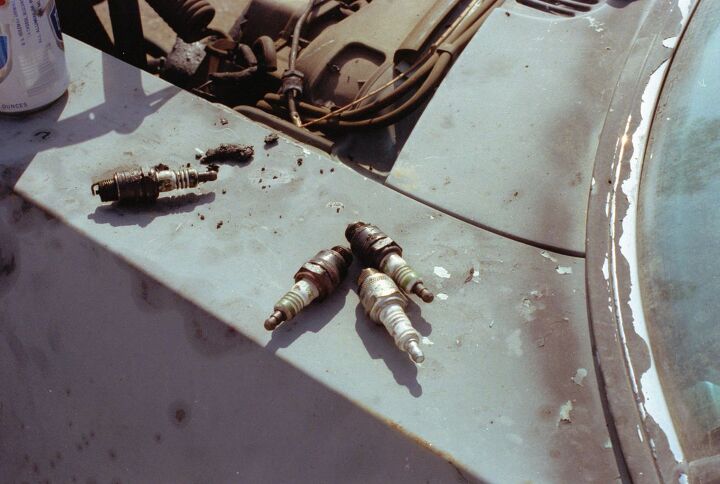

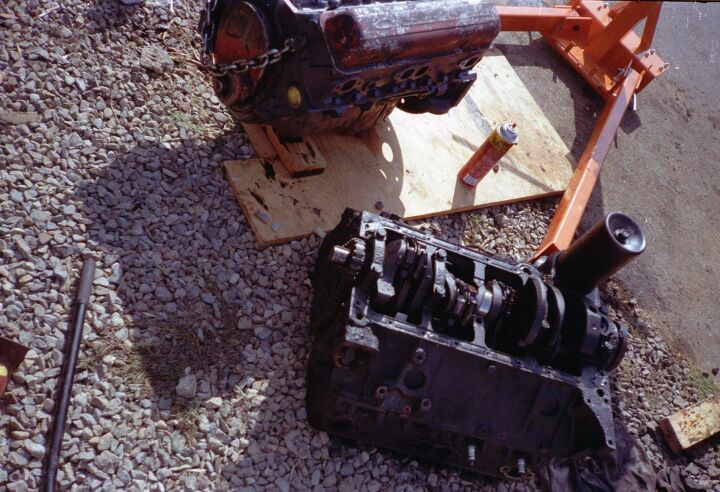

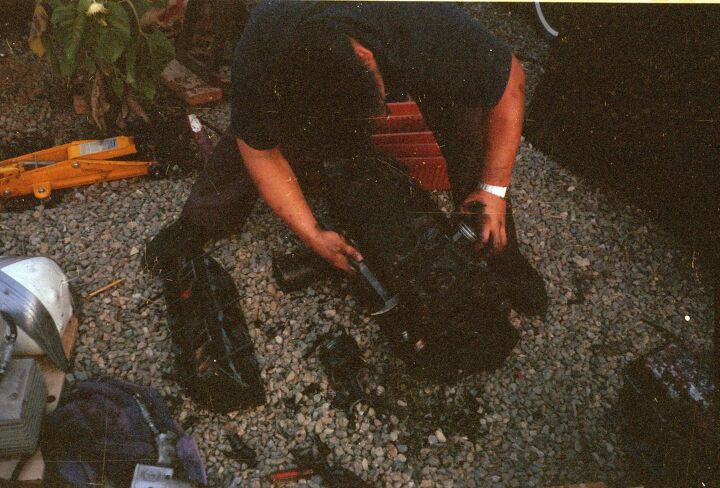

It goes without saying that removing a V8 from a 1960s full-size Detroit car is very, very easy (unless it’s a Toronado or Eldorado, of course). The 283 was out and on the ground after a couple of hours of very leisurely work.

I moved the 283’s valve covers to the 350, to keep the dirt off. Note the old-fashioned canister-style oil filter on the 283.

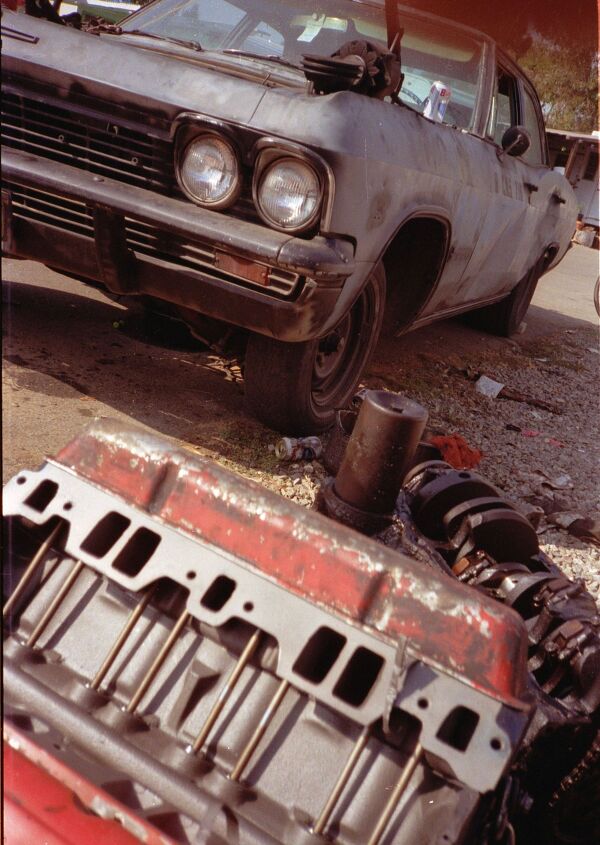

The Irvine Master Plan has no provisions for a scene like this.

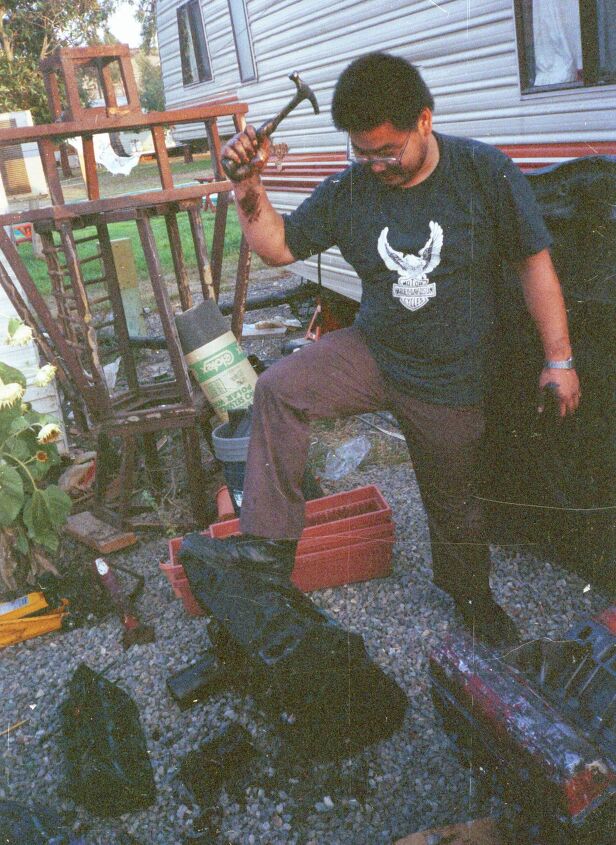

Or this.

I was trying to do the swap as cheaply as possible, but I couldn’t resist dropping $35 on a Quadrajet and intake off a 1970 El Camino at the Wilmington Pick-Your-Part. The cast-iron exhaust manifolds would have to do until I could get to a swap meet for some low-buck headers.

Paul (aka the Chicom Junky Santa), the guy who advised me to try the engine-killing oil flush felt guilty about his advice and came by to help with the swap. We decided to dismantle the 283, just to see how worn out its innards were.

Yes, a thoroughly tired engine. 283s were a dime a dozen then (and, probably, still are), so I didn’t feel any need to save the innards. I donated the crankshaft to a trailer-park artist who wanted to use it as part of a very heavy wind-chime. Clank!

The old oil pan would be swapped onto the new engine, along with all the accessories, timing cover, distributor, etc.

Southern California trailer park tradition mandates storing all your car parts outdoors.

Ready for the heart transplant!

Such an easy swap, with all that room under the hood. Even a 454 transplant would have been no big deal. In fact, the only real snag was the flexplate-to-torque-converter spacing with the 350 and Powerglide; for some reason, the flexplate on the 350 mounted about 3/4″ forward of its location on the 283 crank, which resulted in a gap between the flexplate and the mounting bolts on the torque converter.

By this time, I was down to a few days before The Man’s deadline to leave the trailer park. Fortunately, my friend Chunky ( of “Oh Lord, stuck in the Lodi Volvo again” fame) drove down from the Bay Area to pitch in. He had a good fix for the flexplate-gap issue: since I’d be installing a TH350 soon enough, using a bunch of Grade 8 washers as spacers with Grade 8 bolts 3/4″ longer than the factory torque-converter-to-flexplate bolts should hold together long enough for me to drive the car 430 miles north to Alameda. For some reason, I didn’t take photographs of this LeMons-style fix, but it looked pretty dicey. Worked fine, though!

Since the AC system was deader’n hell, I donated the components to Paul, who later used them to build the world’s most hoopty air conditioner in an F-250.

The 283 block ended up as a sculpture in the Irvine Meadows West Sculpture Garden. As far as I know, it was still there when The Man bulldozed the place 15 years later. Maybe it’s now buried under the asphalt of the parking lot that replaced the trailer park.

And that was that. The new engine ran fine, the Powerglide was perfectly happy with the increased torque, and the buyer for my trailer was ready to move in. Time to head north, for Adventures In Recession Underemployment! Next up: three speeds, two exhaust pipes.

Murilee Martin is the pen name of Phil Greden, a writer who has lived in Minnesota, California, Georgia and (now) Colorado. He has toiled at copywriting, technical writing, junkmail writing, fiction writing and now automotive writing. He has owned many terrible vehicles and some good ones. He spends a great deal of time in self-service junkyards. These days, he writes for publications including Autoweek, Autoblog, Hagerty, The Truth About Cars and Capital One.

More by Murilee Martin

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- EBFlex What an absolute joke. These price games Tesla plays is ridiculous

- Tassos Serious car for serious drivers. Price is good especially considering the value of the USD. Watch out for blue smoke and a plan for a healthy maintenance budget. Otherwise this is a decent used car that could very well be a future classic. AS FOR ME, I’M NOT A SERIOUS PERSON SO I’LL CONTINUE FLEXING MY ANCIENT DIESEL BENZES (REBUILT TITLES) LIKE IT’S SOME KIND OF ACCOMPLISHMENT.

- Fahrvergnugen “enormous power.” I guess ludicrous power must have been taken already. Where's the shazzbot power?

- Probert Just to note: The suspension and braking system have been massively upgraded to match the drivetrain performance.

- MaintenanceCosts They are trying to compete straight across with the BMW iX and Volvo EX90 on price. With a Kia (Boyz) badge. Good luck with that.In the $65k range there would be a case.

Comments

Join the conversation

I wouldn't mind having 1990 gas prices now lol

Burgie, Blatz, and the rest of them may have been bad, but at least they were cheap, and not trendy. I don't mind PBR, but I've been mired in real poverty to drink it ironically like the hipsters. I miss the days when I would go to Save-on Drug, or Rite Aid and get 3 12 packs of Blatz for $10. This story reminds me of driving my pre-wrecked 66 Malibu, and the motor swap I did in the sloped driveway of my apartment in Venice Beach in my 1960 Chevy in 2001.