No Fixed Abode: Return Of The King

So here we are, celebrating forty years of the “Dreier”, or 3-Series, depending on how Euro-wannabe you wannabe. Since I don’t wannabe, I’m going to call it “39 Years Of The 3 Series”. After all, we didn’t get the 320i in the United States until the 1977 model year. When it did arrive, it was a thermal-reacted boondoggle with a tendency to rust out from under the feet of the unlucky first owners.

Although it looked like a million bucks, particularly in “S” trim, and it was one of the dream cars of my pre-teen years, I cannot allow any of you Millennial readers out there to come to the mistaken belief that the E21, as adapted for the American market, was anything other than a shitbox with the lifespan of a fruit fly. It was also easy meat for a Rabbit GTI in any venue from the stoplight drag to the road course. It was, however, expensive, costing about as much as a base Cadillac Coupe de Ville, so at least it had that going for it. The most damning thing I can tell you about the 320i is this: I worked for David Hobbs BMW for much of 1988, and although the newest 320i was just five years old at that point, I never saw one come in for service, and we never took one in on trade.

The “E30” 318i that appeared for the 1983 model year was a major improvement over its predecessor in everything from climate control to rust resistance, but it was “powered” by the same 103-horsepower, 1.8-liter, eight-valve four-cylinder that made the badge on the back of the 1980-1983 320i a comforting lie. I put “powered” in quotes because the E30 318i struggled to break the 18-second mark through the quarter-mile in an era where the Mustang and Camaro were in the low fifteens and even a 1981 Dodge Omni 024 “Charger 2.2” could rip the mark in 17.2 seconds. That’s right: if you were in a brand-new BMW and a three-year-old Dodge Omni pulled up next to you at the light, the only thing that could save you from an ass-kicking would be a swift activation of the turn signal.

But then, one day about halfway through the first year of the 318i’s lukewarm tenure in North America, things changed.

The Three’s big brother, the E28 528e with its low-rev, 2.7-liter “eta” straight-six putting out just 127 horsepower, was a real whipping boy of the automotive media at the time. The spell cast by David E. Davis, Jr.’s infamous near-advertorial for the original 2002 had finally faded to the point where criticizing BMW became not only possible, but profitable. After all, there were plenty of would-be BMW competitors like the Pontiac 6000STE and Dodge Lancer out there, and there was a lot of magazine ad space to be filled. So the same press that had pretended not to notice the unique ability of Seventies Bimmers to go pop-crackle-BOOM fell all over themselves to attack the 528e.

1983 BMW 528e by Cchan199206 (Own work) [ GFDL or CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

True, as far as sports sedans go, the eta-motored Five wasn’t very inspiring. It was the default transportation choice of realtors, yuppie wives, and financial-industry people with children. Pretty much everybody you see driving a Lexus RX350 nowadays would have driven a 528e back then. Some nontrivial percentage of them even took it with a stick, because the Eighties were an era where both men and women were still expected to know how to operate a “standard shift”. My mother had a clutch pedal in her car, as an example, until 2007, long after she was diagnosed with terminal sarcoidosis and well after her sixtieth birthday. Ships of wood, men of iron, you get the idea.The problems with the 528e were all neatly solved by the arrival of the brilliant 533i and the even more brilliant 535i and the sublime 535is and the even more sublime E28 M5, which ushered in the kind of Golden Age at BMW that had previously only existed in the hyperbolic imaginations of autowriters and ad copywriters. The mere existence of the 533i had serious implications for 528e sales because it cost more and therefore was more attractive to realtors and yuppie wives and financial-industry people with children. This meant that production of the US-only eta motor wasn’t going to be as high as it had previously been, unless BMW could find another place for it.

BMW 325e by IFCAR (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

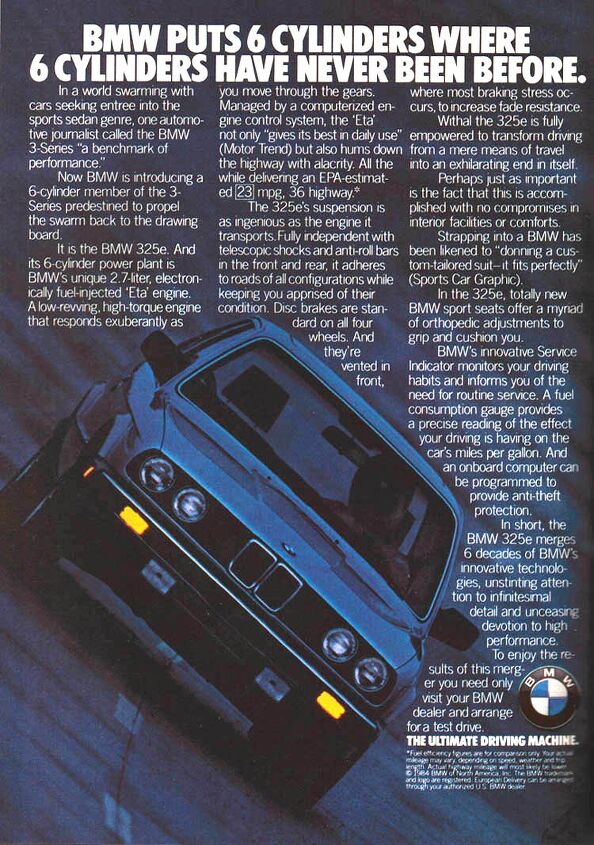

And thus we arrive at the 325e, which was introduced halfway through the 1984 model year as an upscale companion to the 318i. In addition to the 127-horse eta motor, the 325e had a lot of standard equipment and a leather interior in place of the vinyl found in its four-cylinder sibling. Car and Driver called it “smooth as a jet” and recorded a quarter-mile of 16.3@83mph. Finally, a Three that could at least nip at the heels of five-liter Mustangs.More importantly, this was finally the 3-Series that delivered what the 320i had promised when it arrived seven and a half years before. It was luxurious, quiet, effortlessly rapid in traffic, and able to outhandle most of the competition. To drive a 325e in 1984 was to be at the apex of small German cars. You didn’t have to rev it to go quickly – hell, you couldn’t rev it, really. Just snap off shifts at the four-grand mark and watch everything around you disappear into the mirror. The same kind of easy torque that causes people to wax rhapsodic about diesels today was standard equipment thirty-one years ago in the eta-motored Three. It also marked a new seriousness on BMW’s part regarding the American market; there had been a six-cylinder variant of the E21 in Europe for nearly its entire lifetime, and the E30 had a 323i variant from Day One over there, but the company had never bothered to provide one for us.

The arrival of the 325i two years later, with its high-revving Euro-spec six, cemented BMW’s market position and enthusiast prestige for years to come. The four-cylinder variants that followed, the M3 and the sixteen-valve 318is, acquired devoted followings of their own, but it was the 325e and 325i that changed the image of the E30 from “gutless yuppie-mobile” to “legitimate sporting sedan”. These were the cars that formed the basis of BMWCCA racing for years and made the Spec E30 class a viable proposition.

From 1984 to 2012, the naturally-aspirated six-cylinder BMW Three of between 2.5 and 3.0 liter displacement was, to quote a thousand advertisements and editorials, the benchmark by which entry-level sports sedans were judged. It was a product of consistent and admirable excellence, a pleasure to drive and a privilege to own. There were often faster or more stylish options on the market, but none of them had the staying power of the Three.

The first lap I ever took around a racetrack was behind the wheel of my brand-new 330i Sport, as was the first flag I ever took as an autocrosser. During the year I worked for David Hobbs I drove plenty of eta-motored Threes, including a BBS-and-Bilstein-equipped 325es that shocked my teenaged self with its lateral grip and responsiveness. But the strongest memory I have of those cars was a rural day in Ohio back in the summer of 1989.

It was Orientation Day for parents and students at Miami University. My father’s schedule didn’t permit him to waste his time attending such an event, so he commanded that I attend it alone. When I protested that my red Marquis couldn’t possibly make the 117-mile trip to Oxford, Ohio, he handed over the keys to his black 325 and told me to return it at the end of the day.

It wasn’t a 325e, just a plain 325, the vinyl-interior model that replaced the 318i in 1986. No options, no gingerbread, just two doors, five speeds, and a fresh set of Michelins on the fourteen-inch alloys. Down Route 70, I stretched the Bimmer’s legs past 120mph and used the shoulder where I had to. I arrived at school about ninety minutes after leaving the house. Dad was right about the orientation; it was mostly hand-holding shit for kids terrified of the idea that they’d be living away from home. So at around two in the afternoon, I pointed the black BMW’s big chrome bumper out of town with the intent of beating my inbound time. Could I make 117 miles, some of it two-lane, in seventy-five minutes?

I chirped second leaving the last stoplight at Miami and never looked back. Up Route 127, the 2.7 stuttered against the rev limiter in third as I pulled across the double-yellow and blasted past the slow-moving tractor-trailers. When I pulled up in front of the house, the brakes were hot and the fuel tank was empty, and the little digital clock to the right of the tape player said 3:35. Not the 3:28 for which I’d hoped, and a few minutes above my target time. I told my friends, but they didn’t believe me. In 1989, that kind of pace was more the stuff of legends than anything else. And that was appropriate, because that squared-off coupe was, indeed, legendary in its own time, and to this day.

More by Jack Baruth

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- 2ACL I have a soft spot for high-performance, shark-nosed Lancers (I considered the less-potent Ralliart during the period in which I eventually selected my first TL SH-AWD), but it's can be challenging to find a specimen that doesn't exhibit signs of abuse, and while most of the components are sufficiently universal in their function to service without manufacturer support, the SST isn't one of them. The shops that specialize in it are familiar with the failure as described by the seller and thus might be able to fix this one at a substantial savings to replacement. There's only a handful of them in the nation, however. A salvaged unit is another option, but the usual risks are magnified by similar logistical challenges to trying to save the original.I hope this is a case of the seller overvaluing the Evo market rather than still owing or having put the mods on credit. Because the best offer won't be anywhere near the current listing.

- Peter Buying an EV from Toyota is like buying a Bible from Donald Trump. Don’t be surprised if some very important parts are left out.

- Sheila I have a 2016 Kia Sorento that just threw a rod out of the engine case. Filed a claim for new engine and was denied…..due to a loop hole that was included in the Class Action Engine Settlement so Hyundai and Kia would be able to deny a large percentage of cars with prematurely failed engines. It’s called the KSDS Improvement Campaign. Ever hear of such a thing? It’s not even a Recall, although they know these engines are very dangerous. As unknowing consumers load themselves and kids in them everyday. Are their any new Class Action Lawsuits that anyone knows of?

- Alan Well, it will take 30 years to fix Nissan up after the Renault Alliance reduced Nissan to a paltry mess.I think Nissan will eventually improve.

- Alan This will be overpriced for what it offers.I think the "Western" auto manufacturers rip off the consumer with the Thai and Chinese made vehicles.A Chinese made Model 3 in Australia is over $70k AUD(for 1995 $45k USD) which is far more expensive than a similar Chinesium EV of equal or better quality and loaded with goodies.Chinese pickups are $20k to $30k cheaper than Thai built pickups from Ford and the Japanese brands. Who's ripping who off?

Comments

Join the conversation

The HP numbers from the mid 80's shows how lucky we are today. Old Car and Drivers are a hoot to look through. Love your drive story from 1989. Back then I was dumb as a box of rocks. As an Army PFC, I rented an MB 190E for the drive from Butzbach to Frankfurt to celebrate the wall coming down. I remember it being kinda slow, but better than an M2 Bradley. Sheesh I'm old.

I was lobbying hard at the age of 12 for my mom, a realtor of course, to get the 325 in 1988. But Audi was hurting and the lease deal was too good to sway her so she traded the 5000S for an 80 quattro. She changed careers and bought it out later so spent some driving that car when i was of age. I often wonder how those early driving formative years would have shaped my tastes if she had gotten the BMW.