For Memorial Day: The Arsenal of Democracy – The Independents

General Motors was the largest supplier of war materiel to the American armed forces. Ford famously built B-24 Liberators that rolled off the Willow Run assembly line at a rate of one per hour. Chrysler alone built as many tanks as all the German tank manufacturers combined. With those high profile contributions to the war effort made by the big three automakers, it’s easy to forget that the independent automakers (and automotive suppliers as well) also switched over completely to military production.

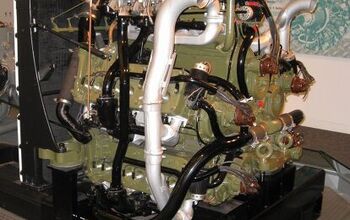

Though car companies made boats and bombers, guns and gyroscopes, helmets and helicopters, really anything they could do for the war effort and keep the doors open, much of the military product development and manufacturing concerned their core competencies. When your company name includes the word “motors”, in wartime you make engines. Sometimes, like Chrysler’s A57 multibank 30 cylinder tank engine, the engines were in-house designs, but more often than not, the automakers produced marine and aviation engines under license from their original manufacturers.

Packard Motor Car made a variety of military engines. In our look at the Big 3, we already saw how Packard stepped to make Rolls-Royce Merlin engines when Henry Ford canceled the deal that Edsel Ford had negotiated with William Knudsen to make 9,000 Merlin 27 liter V12 engines. Henry Ford had earlier indicated to Treasury Sec. Henry Morgenthau Jr. that he was willing to make up to 1,000 planes a day, if the government would let him do it his way, but when Ford found out that Edsel’s deal meant supplying Britain, Henry had a fit, insisting that he’d supply the US government but not the Brits. Packard Motor was eventually selected to fulfill the $130 million order, in part because the Rolls-Royce company had high regard for Packard’s engineering expertise and quality.

That choice proved to be a wise one. Packard’s improvements on the original Merlin made it possible for the P-51 Mustang fighter to be able to operate at a high level of performance at high altitude. That in turn allowed American bombers to have fighter escorts all the way from England to Berlin and back. With a 4% chance of not surviving any one mission, and a quota of 25 missions before rotation back to the States (do the math, 25X4=100%), bomber crews had a horrific casualty rate. Without Packard’s improvements on the Merlin, the daytime bombing raids over Germany would have come at even a much higher cost.

The Packard V-1650, as its version of the Merlin was designated, was not just used in the P-51. It also was used on p-40F “Kittyhawks”, the Avro Lancaster bomber that the British used, and later in the war on some British Spitfires, though RAF pilots considered it unreliable, an opinion not shared by P-51 jockeys.

Less than a year after the contracts were signed the first Packard Merlin ran in August of 1941. It was based on the Mark XX Merlin 28. Right away the Packard engineers started modifying the V16. The first improvements were modest, changing the main bearings from copper to indium plated silver/lead, a trick borrowed from Pontiac. It was Packard’s third iteration of the V-1650 that had the most significant upgrades. The original R-R design used a single stage, two speed supercharger. Packard replaced it with a Wright designed two speed, two stage supercharger.

The more advanced blower meant that the induction system was able to maintain sea level atmospheric pressure even beyond 30,000 feet in altitude. The Packard Merlin was capable of putting out full power up to 26,000 feet and could still generate over 1,270 HP at 30,000 feet. Over the course of the war, Packard built over 55,000 V-1650s.

Though Packard made military aircraft engines based on Rolls-Royce’s Merlin design, the motors they made for naval vessels had their origins a little closer to home. American PT boats were powered by Packard V12s. That engine was essentially a modified Liberty L-12 first used as an aircraft engine in World War One. The Liberty was designed jointly by E.J. Hall of the Hall-Scott engine company, and Jesse Vincent, Packard’s top engine designer. The engine was a SOHC modular design and could be made in 6, 8 and 12 cylinder configurations. Packard built the first prototype, a V8, and the V12 soon after, at the Packard plant on East Grand Blvd in Detroit. Coincidentally, the Packard V12 and the Merlin V12 had identical displacements. This has caused some confusion, particularly since Packard also designated one of their WWI era versions of the Liberty as the V-1650, the same name they would use for the Packard Merlin. As a result it is sometimes erroneously reported that PT boats used a version of the Merlin.

Though original equipment on PT boats was the Packard Liberty V12, in war you have to make do with what you have, so in service some of those Packard engines were replaced with the Invader 168, a 998 cubic inch 265 HP inline six made by Hudson Motors under license from Hall-Scott. The Invader was primarily used as a landing craft engine.

Unlike GM, Ford & Chrysler, who made trucks, jeeps and reconnaissance cars, Hudson’s contributions to the war effort were decidedly not automotive and mostly related to the air war. Hudson’s first military contract was to produce 20mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft guns. Hudson built a million square foot factory in Center Line, Michigan, that employed 4,000 workers making those guns, which Hudson assembled from 1941 to 1943, when the Navy suddenly canceled the contract, awarding it to Westinghouse. Hudson would struggle to meet production quotas on most of their wartime products. The transition from civilian to military production was not always smooth. Though Martin and Curtiss-Wright were relatively happy with the work that Hudson did for them, the Navy felt that Hudson was slow in getting production up to speed.

Eventually Hudson found its niche making airplane parts, and parts of airplanes. Hudson supplied pistons to Wright, B-26 Marauder fuselage sections for Martin, wings for the Curtiss-Wright SB2C Helldiver dive-bomber and the Lockheed P-38 fighter, and armored cockpits for Bell’s P-63 King Cobra fighter. The last major wartime contract for Hudson was to make wings and fuselage sections for Boeing’s B-29 heavy bomber.

In addition, before they moved the Hudson Naval Arsenal into Westinghouse control, the Navy had Hudson produce small runs of specialty products like catapults for launching airplanes.

One interesting factoid about Hudson’s wartime production was their use of female plant guards. Though like many other military suppliers Hudson hired women for most production and inspection positions, using women in security positions was a novel thing and the company publicized it.

Hudson also hired blacks, but in June 1942, when they tried to place African-Americans in production work at the Hudson Naval Arsenal, white workers in a number of departments walked off the job in protest, apparently instigated by elements of the Ku Klux Klan. Remember that many southern whites and blacks had moved north to work in the auto plants. Racial animus would explode in Detroit a year later when a riot that started on Belle Isle eventually led to the deaths of 43 people. In the case of the “hate strike”, though, the secretary of the Navy told the UAW that not only would the Navy fire any strikers, they’d make sure that the strikers would not be able to find work at other munitions plants. Four ringleaders of the strike were fired, with the blessing of UAW leadership. That was not the only labor problem Hudson faced. There were a number of strikes and work stoppages in 1944 and 1945. That may go against the narrative that everyone pulled together for the war effort, but facts are facts.

The last “prewar” Nash rolled off the Kenosha line in January of 1942, the company having already mostly converted to military production. Like Hudson, Nash also devoted most of their wartime production to aviation, not automotive products. Nash was one of seven companies to produce the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 “Double Wasp” radial, building almost 17.000 of them. Nash’s other primary wartime product was Hamilton Standard’s hydromatic variable pitch propellers. At the height of production, Nash was the largest propeller manufacturer in the world, producing even more than Hamilton Standard. By the end of the war, Nash had made over 150,000 propeller assemblies and over 85,000 spare blades. The finished propeller assemblies had over 1,000 component parts each. Nash also made propeller governors and propeller feathering devices.

Additionally, for the duration, Nash supplied over 200,000 pairs of binoculars and cases, 650,000 bomb fuses and over 200,000 rocket motors, plus 44,000 cargo trailers, probably the closest thing to something automotive that the company produced from 1942-1945.

Nash even made complete aircraft. A contract was signed for Nash to supply the Navy with 112 flying boats. The planes were designed, and a factory was planned near Lake Pontchartrain near New Orleans, but the Navy canceled the contract, reimbursing Nash for their expenses. Though they never put fixed wing aircraft into production, Nash did assemble Sikorsky helicopters. In 1943, Sikorsky designed a new model, the R-6 and the Army Air Corps was ready to order but Sikorsky did not have the capacity to meet the orders so they suggested Nash-Kelvinator to do the job. A contract was signed for 900 copters. Sikorsky supplied most of the drivetrain and rotor components, and the fuselages were built in Grand Rapids. Final assembly took place in N-K’s Plymouth Road factory in Detroit. That building would later be American Motors’ headquarters and after that Jeep’s engineering center. The building still stands but is empty, the Jeep personnel having been moved to Auburn Hills in 2009.

Production took a while to start up, primarily because Sikorsky made about 20,000 revisions to the original design. The first production model was tested in Sept. 1944. To test the helicopters, Nash built what was perhaps the smallest airport in Michigan just north of the Plymouth Road plant. When the contract was canceled a week after VJ day, Nash-Kelvinator had built 262 helicopters.

Though this series has been focusing primarily on Detroit based automakers, South Bend based Studebaker, the largest of the independents, was also a major military supplier. They built over 60,000 Wright Cyclone engines for the B-17 Flying Fortress. Like other automakers doing defense work, Studebaker was proud of their effort and took out advertisements featuring B-17s. some of those ads are featured in the photo gallery below.

Studebaker also made the M-29 “Weasel”, a tracked vehicle originally intended to carry commandos used to attack German nuclear research facilities in Norway. In service they were primarily used to resupply front line troops who could not be reached by conventional trucks. Though designed to be amphibious, the Weasel didn’t have much freeboard, so the M-29C was developed with added buoyancy cells and rudders.

Studebaker made thousands of US6 (M16A) 4X4 and 6X6 trucks for the war effort, many of which were sent to the Soviet Union under the Lend Lease program. The Stude trucks performed so well on the terrible roads and in the harsh Russian winters that for a while “Studebaker” was synonymous with “truck” in Russian slang. They were so well built that GIs would see a pretty woman walk by and say “Now she’s a Studebaker”.

Speaking of four wheel drive military vehicles, no discussion of the independent automakers during WWII would be complete without a discussion of the jeep, since two of the three companies involved in the jeep were independents, the third being Ford.

No discussion of the independent automakers during WWII would be complete without a discussion of the jeep, since two of the three companies involved in the jeep were independents, the third being Ford. Though the origins of the name “jeep” are somewhat shrouded, the history of the jeep itself is well documented (though as with all histories there are controversies). [Note: I’m using the convention of capitalizing Jeep when referring to postwar products of Willys/Kaiser/AMC/Chrysler while wartime military jeeps will get a lower case spelling).

As with many WWII era weapons, the jeep’s story begins before the US entered the war. Germany invaded Poland in September 1939. As the Germans quickly conquered most of Europe and North Africa, the US Army realized that it needed a small 4X4 truck capable of going where there weren’t necessarily any paved roads, to use as a reconnaissance vehicle. In early 1940, the Army put out a rush request for prototypes. Over 130 car, truck and other automotive companies were contacted, but most companies felt that they could not meet the 49 day deadline nor the 1300 lb maximum weight, and only Willys-Overland and tiny American Bantam submitted vehicles. Before the competition was judged, though, the Army pressured Ford Motor Company to participate, concerned that a large automaker would be needed to meet anticipated production numbers.

Willys asked for more time, but Bantam, who had been making a lightweight British 4 cylinder car under license, worked day and night and in 49 days they had their prototype. There’s some controversy over just who was involved. Most histories attribute the design to Karl Probst, a Detroit based engineer who was brought in to the project at the request of Bill Knudsen, then head of the National Defense Advisory Committee. It appears, though, that most of the layout and engineering had already been done by Bantam personnel. Probst’s major contribution seems to have been preparing the bid drawings. As such he surely had a role in how the jeep looked, but it’s likely that Probst didn’t “design” the first jeep.

The design brief called for:

- 1,300 lb weight (later changed to 2,160 because the lower weight was not realistic)

- Four wheel drive

- Engine: 85 lb/ft of torque

- Maximum tread width: 47 inches

- Minimum ground clearance: 6.25 inches

- Payload: 600 lbs (hence the 1/4 ton designation)

- Cooling system: capable of allowing sustained low speeds without overheating

Bantam submitted their bid on time, though they fudged the weight specs, their vehicle being significantly heavier than 1,300 lbs. By September a prototype was running. After putting it through over 3,400 miles of torture testing, over 90% on unpaved roads or no roads at all, the Army concluded:

“This vehicle demonstrated ample power and all requirements of the service.”

The testers were so impressed that the Army forwarded Bantam’s blueprints to Willys and Ford, who then submitted prototypes more or less based on the Bantam designs, though the Willys “Quad” and the Ford “Pygmy” did have some significant differences. The Army then ordered 1,500 vehicles from each competitor. Only a handful survive. The Walter P. Chrysler museum has a Willys MA, and there’s a Ford GP in a suburban Detroit Ford dealer’s private collection. After evaluating the three jeeps, the Army decided on a standardized model that was based on the Bantam layout, but incorporated elements from the Ford and Willys designs.

The Bantam had an anemic 4 cylinder engine of fairly ancient British design. The Ford used an engine originally designed for Ford tractors. While those obsolete engines barely met the torque requirements, the Willys “Go Devil” engine was a recent design and had 25% more torque, as well as significantly more horsepower. So the standardized model used a Willys motor.

The Army also preferred the front end design of the Ford, that had a broad, flat hood over the engine which could be put into service carrying cargo or wounded soldiers on stretchers.

No good deed goes unpunished and for their contribution to the war effort, American Bantam was rewarded by the jeep contract being given to Willys. The War Department was skeptical of Bantam’s shaky manufacturing capacity and even shakier corporate finances. Willys-Overland subsequently gave the US government a non-exclusive license to make the jeep using Willys’ specs. Per the government’s wishes, Willys supplied Ford with a complete set of blueprints.

In total, over 700,000 jeeps were built by Ford and Willys, with Ford making slightly more GPWs than Willys made MBs. As a consolation prize, the Army awarded some other contracts to Bantam, but they were not nearly as profitable as supplying the jeep would have been. In an ironic footnote, though neither company had originated the jeep, after the war, when Willys started marketing civilian versions of the MB, Ford challenged their trademark on the name “Jeep”. Ford lost and in 1950 Willys registered “Jeep” as a trademark. In yet another irony, years later Chrysler/Jeep and GM/Hummer would go to court over who owned the trademark on the seven slat front grille of the Jeep (actually the result of the military HumVee being designed by American General while AMC owned Jeep). Chrysler and GM went to court over a front end design that originated at Ford.

Regardless of who designed what parts of the military jeep, it did its job and then some. Ernie Pyle, the great war correspondent, said of the jeep: “It’s as faithful as a dog, as strong as a mule and agile as a goat.” Every one of the US service branches, in both Europe and in the Pacific, used the jeep, as did the forces of Canada, Britain, Australia and New Zealand. The were used for reconnaisance and with mounted guns, as ambulances for the wounded, and as limousines for prime ministers and presidents.

Humble, hard working and never willing to quit, in many ways the jeep symbolizes the “greatest generation”, Americans who fought the war in combat and on the home front, on the front lines and on the production lines.

Again, on this Memorial Day we honor and memorialize their struggles, their successes and their sacrifices.

Note: Most companies making war materiel made sure the public know that they were contributing to the cause. I’ve attached a gallery of wartime advertisements from automakers that feature their military production.

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, the original 3D car site.

More by Ronnie Schreiber

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- MaintenanceCosts What is the actual out-the-door price? Is it lower or higher than that of a G580?

- ToolGuy Supercharger > Turbocharger. (Who said this? Me, because it is the Truth.)I have been thinking of obtaining a newer truck to save on fuel expenses, so this one might be perfect.

- Zerofoo Calling Fisker a "small automaker" is a stretch. Fisker designed the car - Magna actually builds the thing.It would be more accurate to call Fisker a design house.

- ToolGuy Real estate, like cars: One of the keys (and fairly easy to do) is to know which purchase NOT to make. Let's see: 0.43 acre lot within shouting distance of $3-4 million homes. You paid $21.8M in 2021, but want me to pay $35M now? No, thank you. (The buyer who got it for $8.5M in 2020, different story, maybe possibly.) [Property taxes plus insurance equals $35K per month? I'm out right there lol.] Point being, you can do better for that money. (At least the schools are good? Nope lol.)If I bought a car company, I would want to buy Honda. Because other automakers have to get up and go to work to make things happen, but Honda can just nap away because they have the Power of Dreams working for them. They can just rest easy and coast to greatness. Shhhh don't wake them. Also don't alert their customers lol.

- Kwik_Shift_Pro4X Much nicer vehicles to choose from for those coins.

Comments

Join the conversation

Great article Ronnie. I was excited to see that you visited the GM Heritage Center in MI. For those who live anywhere near Buffalo, NY, the GM Tonawanda Engine plant is opening its doors to the public for an exclusive free Open House on Friday, June 17 from noon - 8 p.m. We will have the Pratt & Whitney engine at the Open House, with an antique military vehicle display, along with numerous other displays. We received a letter from a WWII pilot that drove a plane with our engine in it, praising the quality and performance of the engine! We are so proud that we could play a small part in helping our military win that war and would be proud to do it again if the need arose.

"Packard’s improvements on the original Merlin made it possible for the P-51 Mustang fighter to be able to operate at a high level of performance at high altitude." Good general writeup, Ronnie, but uh, no. The American aircraft industry was well behind Britain on superchargers. No point in wasting pages on details, but you should read Graham White's book "Allied Piston Aircraft Engines of WW2", published by the Society of Automotive Engineers. White is a US citizen, and regarded as an expert on the topic. I'll summarize: Rolls Royce had already designed a new crankcase and heads for the Merlin and completed the R&D. Trouble is, they couldn't get the downtime to implement the changes, because they were in the middle of a serious shooting war. Everybody and his dog wanted a Merlin in their plane. Ford did manufacture 30,400 Merlins at Trafford Park, their factory in England, and did a fine job from all accounts. So why Ford couldn't bring himself to make the Merlin in the US can only be laid at the doorstep of his own weirdo thinking. Packard got the nod to make Merlins, and after changing all the drawings over from Whitworth and BA fasteners to SAE and UNF, made the very latest version of the Merlin with the two stage/two speed supercharger and new block castings that RR was too busy to do. What Packard did do was to get Wright Aeronautical to design a new gear drive to the superchargers. Not trivial, but certainly not at the same level of difficulty as designing superchargers themselves, where the US was far behind Britain. Packard also used Bendix rather than SU carburetors, etc. Also, Continental also geared up and made Merlins as well, a little known fact.