Book Review: Stealing Cars

TTAC’s had periodic posts about car theft, from a recent news item on a student project disappearing in the night ( here) to hacking into a car ( here and here). A recent book however provides a, well, book-length treatment.

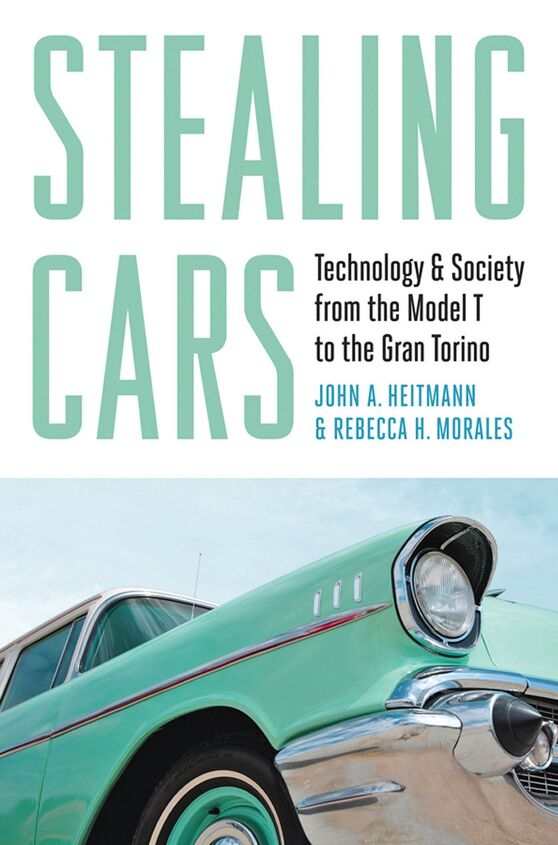

Stealing Cars: Technology & Society from the Model T to the Gran Torino ( Johns Hopkins, 2014. ISBN 978-1-4214-1297-9) is an examination of the phenomenon of car theft through the era of the automobile. Authors John A. Heitmann and Rebecca H. Morales lead off with this quote

“‘When I leave my machine at the door of a patient’s house I am sure to find it there on my return. Not always so with the horse: he may have skipped off as the result of a flying paper or the uncouth yell of a street gamin, and the expense of broken harness, wagon, and probably worse has to be met.’ That solitary impression soon proved to be wrong.” (p. 7)

First, there’s the historian at work, ranging from the first report of car theft in the Horseless Age of 1902, to the new methods of stealing cars noted on TTAC. Then there’s the organization behind it, or the lack thereof: from joyriding and local transportation in the early days (90% of all thefts, corresponding to a 90% recovery rate), to criminal operations seeking entire cars or merely parts – from pulling tires off cars during the WWII era of rationing rubber to cartels today paying for stolen cars with drugs. This thread is backed by an appendix with tables of data.

Then there’s the response to car theft, from the individual level to the lobbying of insurance companies. Technological responses were one avenue. These ranged from ignition keys (though the Model T only had 24 types of keys, with the type stamped on both the key and the starter plate; p. 12) to digital rolling codes tied required to enable the ECU (engine control unit computer). As the authors detail, all had defects – and all can be circumvented by stealing a key. Institutional responses began with the 1919 Dyer Act; for decades a central focus of the FBI was car theft, helped because it so frequently crossed crossed borders. Over time this extended to a system VINs and car registrations that sought to make it hard to remarket stolen parts or to get a stolen vehicle titled. Again, this system has holes. Finally there are sociological responses, particularly the development of garages and gated communities (pp. 73-77).

International theft figured from early on. Canada and Mexico were natural destinations, but on the East Coast rings such as that headed by Gabriel “Bla-Bla Blackman” Vigorito for over two decades (1930s-1950s) shipped cars to Europe and South America, grossing over $1 million in 1952 (pp. 61-3). The book is particularly detailed on the Mexican connection, reflecting the particular contribution of Morales. But it’s also empirically important: the top 10 theft “hot spots” stretch from Washington State through California, particularly near intersections of major highways that are trans-shipment points for drugs (Chapter 5 and Table 4.5 p. 173).

Then there is the depiction of car theft; Heitmann is a devoted watcher of movies and more generally an observer of automotive culture (the subject of an earlier book). Scattered throughout are references to a dozen-plus films, a handful of novels, and of course computer games. Press stories on car theft, ads for gadgets, and other miscellany are sprinkled throughout the book. Then there’s the racial aspect: joyriding whites were shuttled to dad, blacks were carted to prison. That was fine with J Edgar Hoover.

All of this makes for a fun book, and a quick read (159 pages of text). However it’s also disjointed; the authors love anecdotes, and don’t want to leave the best out. The narrative suffers, but quite frankly most on TTAC would probably rather have the anecdotes than the narrative. The book has no maps and only a few photos; it should have more! Likely the publisher resisted, and the authors wanted to get it done. It certainly is not because they lack in such materials: I invited John Heitmann to speak to my auto industry students in May 2014, and he came with a fascinating array of powerpoint slides and additional tales. (For those who want more, join the Society of Automotive Historians (of which he is currently president) or read through his essay on sources and copious footnotes.)

For additional quotes and details, see student journal entries on five chapters under the “Stealing Cars” pull-down menu on the Economics 244 Auto Industry web site at http://econ244.academic.wlu.edu/. Order your own copy from Amazon as either an inexpensive hardcover or for Kindle.

Mike Smitka is an economist at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. He's been a judge of the Automotive News PACE supplier innovation awards since they began in 1994. His household's vehicles are a 2014 Chevy Cruze, a 2013 Honda CR-V and a 1988 Chevy pickup. Find his auto industry course at <a href="http://econ244.academic.wlu.edu/">Econ 244</a>; he also blogs with David Ruggles at <a href="http://autosandeconomics.blogspot.com">Autos and Economics</a>.

More by Mike Smitka

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Probert They already have hybrids, but these won't ever be them as they are built on the modular E-GMP skateboard.

- Justin You guys still looking for that sportbak? I just saw one on the Facebook marketplace in Arizona

- 28-Cars-Later I cannot remember what happens now, but there are whiteblocks in this period which develop a "tick" like sound which indicates they are toast (maybe head gasket?). Ten or so years ago I looked at an '03 or '04 S60 (I forget why) and I brought my Volvo indy along to tell me if it was worth my time - it ticked and that's when I learned this. This XC90 is probably worth about $300 as it sits, not kidding, and it will cost you conservatively $2500 for an engine swap (all the ones I see on car-part.com have north of 130K miles starting at $1,100 and that's not including freight to a shop, shop labor, other internals to do such as timing belt while engine out etc).

- 28-Cars-Later Ford reported it lost $132,000 for each of its 10,000 electric vehicles sold in the first quarter of 2024, according to CNN. The sales were down 20 percent from the first quarter of 2023 and would “drag down earnings for the company overall.”The losses include “hundreds of millions being spent on research and development of the next generation of EVs for Ford. Those investments are years away from paying off.” [if they ever are recouped] Ford is the only major carmaker breaking out EV numbers by themselves. But other marques likely suffer similar losses. https://www.zerohedge.com/political/fords-120000-loss-vehicle-shows-california-ev-goals-are-impossible Given these facts, how did Tesla ever produce anything in volume let alone profit?

- AZFelix Let's forego all of this dilly-dallying with autonomous cars and cut right to the chase and the only real solution.

Comments

Join the conversation

Quote from my mechanic: "30 years in the business, and I've never had a customer be sorry when their car is stolen. They all just hope to God that it isn't recovered." Car theft is just a minor inconvenience. Get a police report, call a cab, drive a rental for a week, pick-up you new car. I guess it would suck if you were driving something rare, but thieves are looking for stuff that's easy to chop and/or resell.

Seems to me the references to video games would be inappropriate in a book covering only Model T - Gran Torino.