We Don't Need No Stinkin' Badges!

There's a great deal of controversy in automotive circles these days regarding the advantages and disadvantages of parts-bin and badge engineering. Parts-bin engineering has been hailed as an efficient way for manufacturers to fully utilize their mechanical resources. Badge engineering has been demonized as an automaker's attempt to pull the wool over consumers' eyes. Although that analysis isn't a million miles from the truth, further explanation is in order.

A manufacturer practicing parts-bin engineering builds more than one model using the same basic components. Examples of parts-bin engineering include the Honda Civic, Del-Sol (1990s) and the current CR-V. On the home front, parts-bin engineering usually means sharing platforms, engines and drive trains. Chrysler was famous (or infamous) for developing a wide variety of vehicles from its "K" platform: family sedans, wagons, minivans and the Daytona sports coupe. Today's Daimler-Chrysler consumers can order the same Hemi engine in a wide range of Dodge, Chrysler or Jeep products.

If properly executed, parts-bin engineering is a boon to both manufacturer and consumer. The parts commonality keeps new model prices low. It helps manufacturers bring exotic models and "niche" products to market quickly and efficiently. The much-admired Pontiac Solstice is a classic example of a parts-bin engineered special. GM's roadster uses many parts shared with the Chevrolet Cobalt, which in turn shares components with the Chevrolet HHR "family-truckster" (apologies to Clark Griswold). This is the very definition of parts-bin engineering: distinct models with different purposes and personalities sharing many of the same parts.

Badge engineering is parts-bin engineering's evil twin. A manufacturer practicing badge engineering offers virtually identical vehicles under more than one of its automotive name plates. In most cases, it's easy: only a vehicle's trim, lights and badging are changed. In others, sheetmetal and suspension tweaks may disguise the practice. There's no small amount of debate about where you draw the line between bin and badge. How can two cars that look so different– the Pontiac Solstice and the Saturn Sky, the Chrysler 300 and the Dodge Charger– be nothing more than badge-engineered clones? Is Caddy's 'new' Euro-spec BLS its own man, even though it's little more than creased sheetmetal sitting on a Saab 9-3? Generally speaking, badge engineering is like the Supreme Court's definition of pornography: you know it when you see it. Or, in some cases, drive it.

American manufacturers aren't the only ones badge engineering their way into mediocrity, but they're certainly the worst offenders. The US automakers' move from bin to badge was a gradual process. In the 1950s, the vehicles sold by a manufacturer's various divisions were quite different products (e.g. a '55 Buick and Chevy). By the '60s, Ford, GM and Chrysler all produced vehicles for their house brands that shared chassis, platforms and engines (e.g. the Chevrolet Camaro and the Pontiac Firebird). By the late 70's/early '80's, badge engineering had spread the plague; nearly every American car company offered virtually identical cars throughout its portfolio. The trend continues.

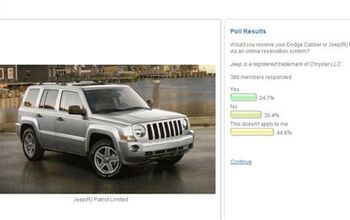

Except for trim and some minor options, a Cadillac Escalade is no different from a Chevrolet Tahoe or GMC Yukon. (I am tempted to rip GM for charging Cadillac prices for a Chevrolet, but they only do it because they can.) The Ford Explorer and Mercury Mountaineer are the same SUV, as are the badge-engineered Ford Escape, Mercury Mariner and Mazda Tribute. Sadly, even Daimler-Chrysler is getting into the act. Its latest Jeep offerings, the Patriot and Compass, have Dodge counter-parts. The Liberty is nearly identical to the Dodge Nitro, though different body panels and a new 4.0 litre Nitro-specific engine may move this pair from badge to bin. The Compass is a Caliber in drag– AND it's the first Jeep that's not off-road capable.

To the casual observer, badge engineering looks like parts bin engineering. Parts-bin engineering involves sharing key components to create thoroughly unique vehicles; badge engineering is little more than "copying and pasting" an entire vehicle from one brand to another. If plagiarism is wrong in journalism, why should it be acceptable in the automobile business? Parts sharing is as old as the Model T, but the best bin-engineered cars are unique in both visual style and mechanical character. The Honda Odyssey minivan is a far different beast than its platform partner, the Ridgeline pickup truck. Compare that to the invidious differences between a Ford Fusion, Mercury Milan and Lincoln Zephyr.

The domestic auto industry is, or at least should be, smarter than that. Unfortunately, many board members are not "car guys." They seem to know as much about a vehicle's inherent appeal as they do about astrophysics. They also appear disconnected from their foreign competition's products and vehicle development process. All they care about is feeding their bloated dealer networks with enough products (as cheaply as possible) to keep the assembly lines churning, maintain market share and keep the corporate mothership afloat.

Although it's a short-term tonic, badge engineering is a long term drag. Manufacturers save money on components and tooling, but they create competition amongst their own brands while destroying each brand's unique character. Parts bin engineering stimulates creativity. Badge engineering kills creativity, divisions and, eventually, the companies that rely upon it.

More by Thomas Bernard

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Dartdude The global climate scam is a money and power grab. If you follow the money it will lead you to Demo contributors or global elitists. The government needs to go back to their original purpose and get out of the public sector.

- FreedMike Miami is a trip - it's probably the closest thing we have to Dubai in this country. If you are into Lambos and the like, definitely go - you'll see a show every night. These condos fit right in with the luxury-brand culture - I'm surprised there isn't a Louis Vuitton or Gucci building. I was in Miami Beach in January with my fiancee, and we shared a lovely lunch that consisted of three street tacos each, chips and salsa, and two sodas. Tab: $70.00, with tip. Great town, assuming you can afford to live there.

- Kjhkjlhkjhkljh kljhjkhjklhkjh Pay money to be inundated in Adverts for a car that breaks when you sneeze? no

- Laflamcs My wife got a new 500 Turbo in 2015. Black exterior with an incredible red leather interior and a stick! The glass sunroof was epic and it was just about the whole roof that seemed to roll back. Anyway, that little bugger was an absolute blast to drive. Loved being run hard and shifted fast. Despite its small exterior dimensions, one could pile a lot into it. She remember stocking up at COSTCO one time when a passerby in the parking lot looked at her full cart and asked "Will it all fit?" It did. We had wonderful times with that car and many travels. It was reliable in the years we owned it and had TONS of character lacking in most "sporty" car. Loved the Italian handling, steering, and shift action. We had to trade it in after our daughter came along in 2018 (too small for 3 vacationers). She traded it in for a Jeep Renegade Latitude 6 speed, in which we can still feel a bit of that Italian heritage in the aforementioned driving qualities. IIRC, the engine in this Abarth is the same as in our Renegade. We still talk about that little 500..........

- Rochester If I could actually afford an Aston Martin, I would absolutely consider living in an Aston themed condo.

Comments

Join the conversation