Rare Rides Personas: Powel Crosley Junior, Tiny Cars, Radio, and Baseball (Part VI)

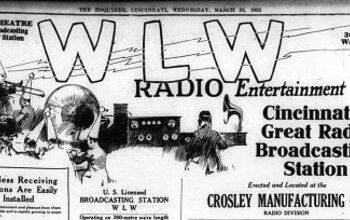

Powel Crosley Junior’s life was in expansion mode in the late 1920s, both professionally and with regard to real estate. Previously, we covered his AM radio goals via the ever more powerful 700 WLW station, his new company HQ in Cincinnati, and the growth of his personal real estate with new estates in Cincinnati and Sarasota. But those goings-on didn’t distract Crosley from the entrepreneurial interests he always maintained. Let’s talk about airplanes.

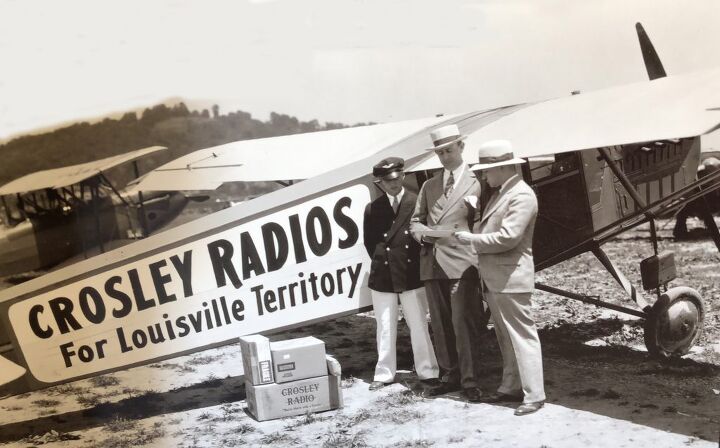

Around the time he was building his new estates, Crosley was also working on his aeronautical interests. He added a new entity to his portfolio called the Crosley Aircraft company and made himself the president of the organization. He needed some land upon which to conduct his airplane venture, so he bought an airfield spread across some 93 acres to the north of Cincinnati. Previously Crosley had purchased Waco 10 planes for marketing purposes, branded them with his logos, and renamed them to Crosley Stork (above).

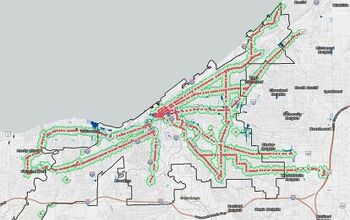

The new Crosley Airport was located in the undeveloped and railroad-focused suburb of Sharonville, Ohio (where your author is writing this article right now). The land the airfield occupied was notable not only for its Crosley usage, but for what it became decades later: Today it’s the site of the Sharonville transmission plant, which used to make C3-based 5R transmissions for global Fords, and today builds Super Duty transmissions.

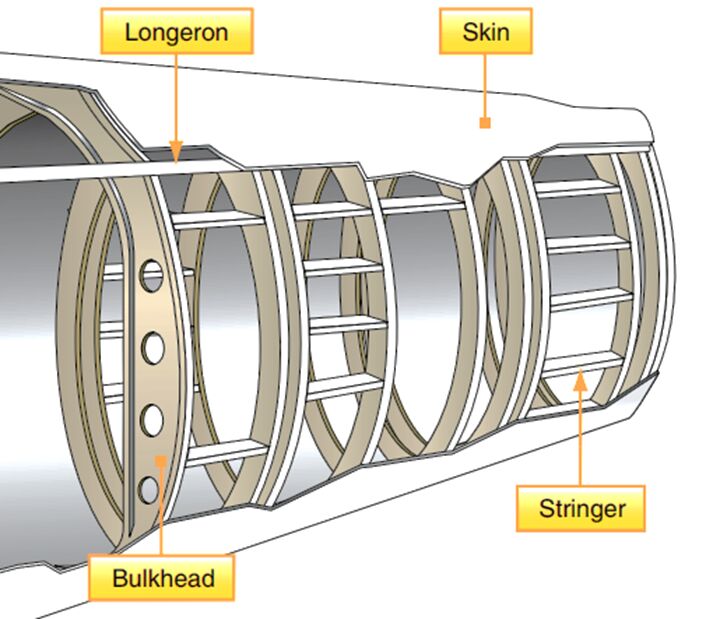

Land secured, Crosley assigned employee Harold Hoekstra to work up a new airplane. Hoekstra’s first design was a single prop biplane called “Moonbeam.” The new plane was different from most plane designs as it used square-shaped tube longerons (see figure) in the fuselage instead of round ones.

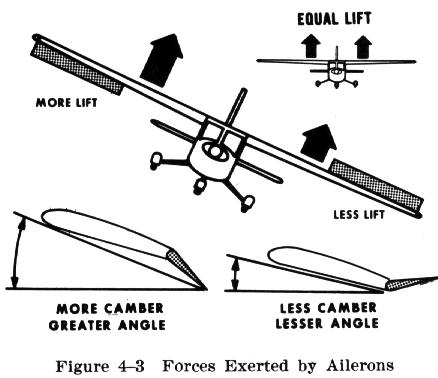

Another unusual feature was its torque-tube-operated controls, instead of the common cable-operated mechanisms of the day. Additionally, the Moonbeam had ailerons made of corrugated aluminum, which today seems a better material than the wood or canvas used in the Twenties. The plane also gave Crosley the chance to build something he enjoyed: Engines. Moonbeams were powered by an inline four-cylinder Crosley engine good for 90 horsepower. Some testing was also done with a more powerful engine from Warner Scarab.

Unfortunately, testing was as far as Crosley’s airplane aspirations went - the company designed and built five total aircraft. The first example held three people, there was one with a capacity of four, and the following two were single-passenger. The company’s final build was a two-place biplane. The first three-passenger Moonbeam took flight on December 8, 1929.

And that date might give some indication of what happened to the company. The Great Depression officially kicked off a couple of months prior on Black Tuesday and meant it was no longer economically advisable to continue airplane development. Crosley shuttered Crosley Aircraft and got rid of Crosley Airport.

The only physical evidence of the company’s existence today is a sole remaining plane, the last the company produced. The two-place Moonbeam identified as N147N lives at the Aviation Museum of Kentucky, in Lexington. It wasn't the end of airplanes for Crosley employee Harold Hoekstra, however. He left Crosley after a time and eventually became the Chief of Engineering and Design at the FAA.

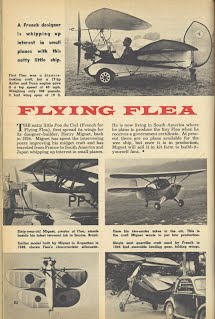

Crosley’s airplane dream was not to be, and he was immediately on to other ventures. However, a Crosley test pilot persisted with a different idea. In 1933 Edward Nirmaier built an example of a French design, the HM. 14 Pon du Ciel, or Flying Flea. The design by Henri Mignet was meant to be a simple plane kit that even an amateur could build at home, and teach themselves to fly.

Crosley liked the idea and asked Nirmaier to build an example in 1935. Powered by a Crosley engine, the Mignet-Crosley Flea was the first HM. 14 built and flown in the United States. Crosley believed the Flea would prove a popular and affordable aircraft for US consumers.

The Flea worked, and it did fly. After several successful flights, Crosley sent it to the Miami Air Race. The Flea won a trophy, and then promptly crashed. The high-profile accident killed the idea of the Flea in the United States quickly and completely, though it persisted in use in France and England for a short while. Finally, European crashes (by non-pilots who built a plane at home) led people to believe the Flea was a bad idea, and it ceased to exist.

Shortly after he finished his initial airplane dalliance, Crosley expanded the home goods and appliances side of the business. Goods and auto parts sales were the funding vehicles behind the real estate, planes, and other expensive ventures soon to be. With the Depression ongoing, Crosley ventured into refrigerators for the first time.

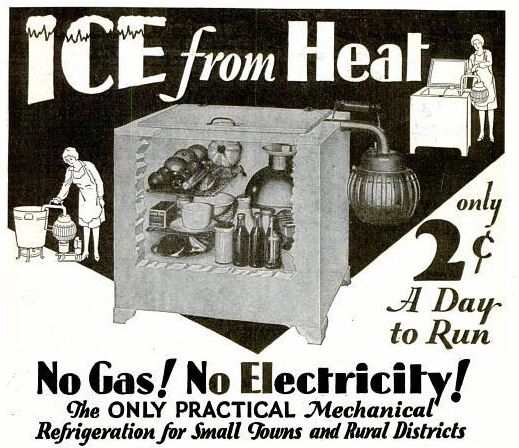

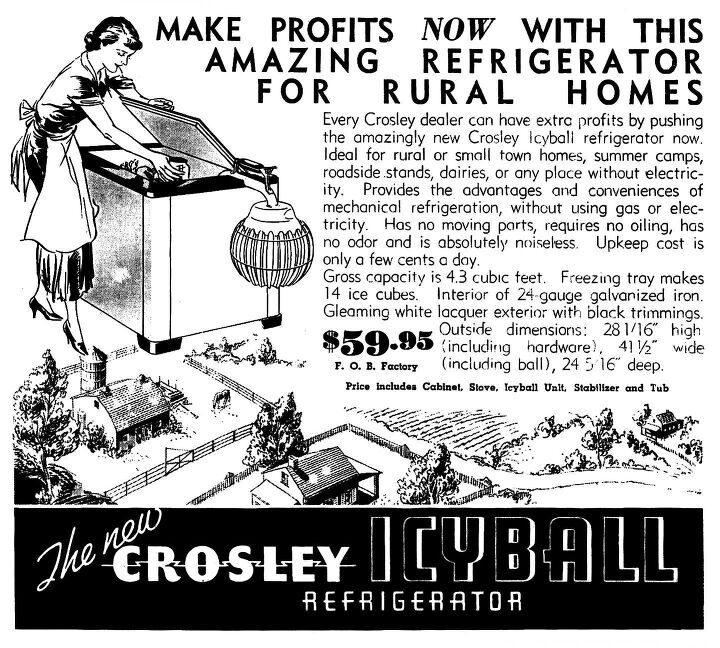

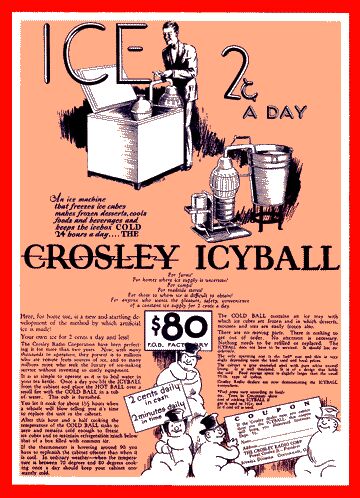

The first of its type was called the Crosley Icyball. Icyball’s design was not Crosley’s own, but rather designed in 1927 by Canadian David Forbes Keith. Keith received a patent in 1929 and sold its rights to Crosley almost immediately. Like his first radio, Crosley’s first refrigerator required no electricity.

The Icyball’s design was one of gas absorption. Such refrigerators cool via evaporation of a given refrigerant, and absorption by another medium. In the Icyball, refrigeration was via evaporation of ammonia into the water. The system pulled heat from the refrigerator cabinet using two metal balls.

One of the balls was “hot,” and contained the absorption material (water). The “cold” ball contained the ammonia. These were joined together via a U-shaped pipe, which allowed ammonia gas to move between the balls. Ammonia evaporated into gas (and increased pressure), which pulled heat from the fridge cabinet, and then was absorbed into the water in the hot ball.

The fridge required a recharge process to its water and ammonia daily, as that was about the max term of its cooling capacity. It wasn’t a simple process: The ammonia ball was removed and then dunked in cool water, while the water ball was heated via propane to boil off the ammonia the water absorbed and turn it back into a gas.

This increased the pressure in the system (sitting in the customer’s kitchen) to about 249 psi. That caused the ammonia to transfer back to the cold ball, where it was kept cool by the water. Then it was time to switch the system and put the hot (water) ball into the cool water. That dropped the pressure, which caused the ammonia in the cold ball to start evaporating again.

At that point, it was “recharged” and ready to go back into the fridge cabinet. The cabinet itself had antifreeze in it, which moderated the flow of cooling, and kept the cold (ammonia) ball working longer. Great care was required in the process as if the warming bath was too hot, the water would boil and ruin the ammonia. If the cold bath got too warm, the ammonia wouldn’t condense and the system would not refrigerate.

Even though it was a pain in the rear to keep it going, the powerless Icyball proved popular. Crosley marketed the Icyball to rural homes that were without electricity, which opened a whole new world of food safety and preparation for such a customer. At $59.95 ($1,038 adj.) the company sold hundreds of thousands of Icyballs. They remained in production through the end of the Thirties, before the electric grid was complete enough to end the Icyball.

A taste of refrigerator success caused Crosley to feel the innovative urge toward more traditional, powered refrigerator units. In 1932, he patented an idea that changed every single refrigerator made since, including the one in your kitchen right now. We’ll pick it up there next time.

[Images: Crosley, FAA, Ashburn Aviation Museum]

Become a TTAC insider. Get the latest news, features, TTAC takes, and everything else that gets to The Truth About Cars first by subscribing to our newsletter.

Interested in lots of cars and their various historical contexts. Started writing articles for TTAC in late 2016, when my first posts were QOTDs. From there I started a few new series like Rare Rides, Buy/Drive/Burn, Abandoned History, and most recently Rare Rides Icons. Operating from a home base in Cincinnati, Ohio, a relative auto journalist dead zone. Many of my articles are prompted by something I'll see on social media that sparks my interest and causes me to research. Finding articles and information from the early days of the internet and beyond that covers the little details lost to time: trim packages, color and wheel choices, interior fabrics. Beyond those, I'm fascinated by automotive industry experiments, both failures and successes. Lately I've taken an interest in AI, and generating "what if" type images for car models long dead. Reincarnating a modern Toyota Paseo, Lincoln Mark IX, or Isuzu Trooper through a text prompt is fun. Fun to post them on Twitter too, and watch people overreact. To that end, the social media I use most is Twitter, @CoreyLewis86. I also contribute pieces for Forbes Wheels and Forbes Home.

More by Corey Lewis

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Redapple2 Dear lord ! That face. HARD NO.

- Urlik Let’s ban for all. Having that data anywhere leaves it open to the Chinese government potentially hacking systems to get the data.

- Redapple2 Gen 1 - 8/10 on cool scale.Gen 2 - 3/10.

- SCE to AUX "...to help bolster job growth and the local economy"An easy win for the politicians - the details won't matter.

- Kjhkjlhkjhkljh kljhjkhjklhkjh so now we will PAY them your tax money to build crappy cars in the states ..

Comments

Join the conversation

Came for the airplane, stayed for the ice ball. Ironically ice balls and airplanes still don't go well together :)

The Flying Flea has a fascinating story and served, inadvertently, to broaden the understanding of aircraft design. The crash described in the article is only part of the tale.