Rare Rides Personas: Powel Crosley Junior, Tiny Cars, Radio, and Baseball (Part V)

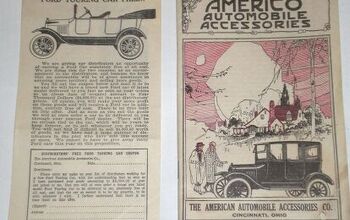

Today we return to the Powel Crosley Jr. story, in 1928. As an aftermarket car parts company owner, Crosley saw business diversification opportunities in the burgeoning field of home appliances. In his first foray, he took on established phonograph manufacturers with his value priced Amerinola.

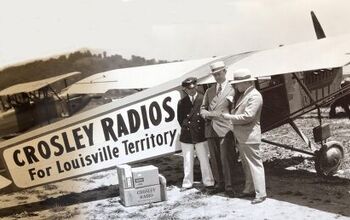

Then as broadcast radio entered public consciousness in the early and mid-Twenties, Crosley began selling simple radios that didn’t require an outside power source. From there, the new Crosley Radio Corporation branched out into powered radios via the low-priced Pup.

Once again, Crosley took on established players like RCA by offering a comparable radio at a fraction of the price. But once customers had their radios in hand, Crosley ran into an issue: It was 1928 and there was nothing to listen to.

Note: Before proceeding you may need to go back and read Part IV in this series, which had a publishing issue and was invisible to most of you for a while after it went live.

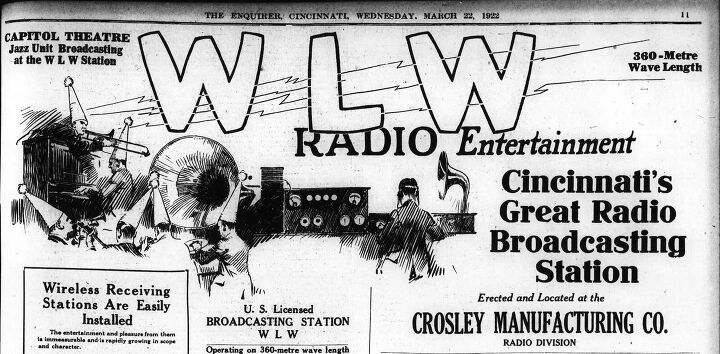

Crosley knew that the radio would continue to have limited appeal as long as radio stations were locally oriented around major cities. Crosley already had his own radio company - Crosley Broadcasting Corporation - which he’d started in 1922. Based in Cincinnati, the 700 WLW radio station used a 50-watt signal.

That was a typical power figure for the time, and meant that while the station had regular programming it only reached those in the immediate Cincinnati area. The low power norm caused an additional problem for the fast selling Pup radio: With its regenerative receiver and simplistic one-tube design, it wasn’t great at receiving radio signals unless they were strong.

Ever the innovator, Crosley realized that he could kill several birds with one stone. By increasing the wattage of WLW, it would reach further than Cincinnati, cause more people to want radios, increase the station’s profitability, and mean that Crosley Radio could build its products more cheaply. Stronger radio signals meant less effort needed to go into the receiver of his radios.

Crosley quickly upped the power of 700 WLW to 100 watts. That figure jumped almost immediately to 500 and then 1,000. Crosley hired a local novice radio engineer from University of Cincinnati (the school he’d dropped out of) to design and build the station’s first few transmitters. Though 1,000 watts was reached in 1924, the station’s power increased again to 5,000 watts the next year.

The next big power jump was in 1928, when WLW increased its wattage to 50,000 (50 kilowatts), and received an immediate claim to fame: It was the most powerful commercial radio station in the world. As other stations joined the 50 kilowatt club, WLW remained the first such station in the country to keep a regular broadcasting schedule.

At 50 kilowatts WLW had quite a range, and could be heard in New York City and Florida as long as the weather was clear. Around 90 percent of the US population could tune in to WLW with regularity. But that wasn’t enough power for Crosley. Hold onto that thought for later.

Elsewhere in business, Crosley built a new headquarters in 1928. Located northwest of downtown Cincinnati in the Camp Washington neighborhood, it was just down the road from Clifton where Crosley lived most of his life. The building housed office and factory space, and was designed by local architect Samuel Hannaford who’d also designed Cincinnati’s city hall, and Music Hall.

The building’s boxy shape was made to look like a radio, and once it was finished was topped with the powerful WLW radio tower. The first seven floors of the structure were used as factory and design space for the company’s various wares, while the eighth floor and smaller tower were offices.

The building was in steady use through the Eighties, but eventually fell into disrepair, abandonment, and was condemned in 2012. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2015, and is presently owned by a private developer. There have been plans to turn the building into loft apartments, but they’ve never materialized.

Further northwest of the new Crosley Building, there was another Crosley structure nearing its completion. As he’d suddenly found himself a man of wealth and business distinction, Crosley commissioned a suitable new residence. Located in the Mount Airy neighborhood of Cincinnati, the Tudor Revival estate was designed by Dwight James Baum. The 18 acre plot was named Pinecroft.

The estate fell into disrepair some time after it passed from Crosley’s ownership, and was unoccupied for many years. Subsequently it was renovated and restored by a local preservation association, alongside a catering company that took ownership. The house was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2008. The catering company still owns the estate today, and uses it as an event space.

Crosley took a third major real estate action in 1928 and 1929, this time outside Cincinnati. Located in Sarasota, Florida, the new house was a secondary home to escape harsh Cincinnati winters. Larger than his Cincinnati residence, the house was on a 63-acre plot of land (presently 45 acres). Crosley commissioned it in a Mediterranean Revival style, at some 11,000 square feet.

Called Seagate, the property was sited on Sarasota Bay. Crosley picked up the land at a discount after a planned subdivision on the acreage failed. The home was designed by New York architect George Albree Freeman Jr. Construction was completed in a quick 135 days, and the house had 10 bathrooms and 10 bedrooms.

Crosley owned the property until 1947, when it was sold to a Floridian family who lived there until 1977. A few years later it was purchased by troubled Ottawa-based developer Campeau, who planned to ruin the property by turning it into condos and a clubhouse. However, those plans fell through and the entire property was added to the National Register in 1983.

Subsequently Seagate was abandoned, then restored by a local nonprofit established especially for the property. Seagate is operated by the nonprofit today as an event space. The University of Florida purchased 28 acres of the estate's original land in 1991 to use for campus expansion.

Though he was quite busy with real estate in the late Twenties, Crosley found time to expand his consumer appliance business into other areas, while simultaneously taking an interest in local sports. We’ll pick up with some refrigerators and the Reds in our next installment.

[Images: Crosley, Pinecroft, Seagate]

Become a TTAC insider. Get the latest news, features, TTAC takes, and everything else that gets to The Truth About Cars first by subscribing to our newsletter.

Interested in lots of cars and their various historical contexts. Started writing articles for TTAC in late 2016, when my first posts were QOTDs. From there I started a few new series like Rare Rides, Buy/Drive/Burn, Abandoned History, and most recently Rare Rides Icons. Operating from a home base in Cincinnati, Ohio, a relative auto journalist dead zone. Many of my articles are prompted by something I'll see on social media that sparks my interest and causes me to research. Finding articles and information from the early days of the internet and beyond that covers the little details lost to time: trim packages, color and wheel choices, interior fabrics. Beyond those, I'm fascinated by automotive industry experiments, both failures and successes. Lately I've taken an interest in AI, and generating "what if" type images for car models long dead. Reincarnating a modern Toyota Paseo, Lincoln Mark IX, or Isuzu Trooper through a text prompt is fun. Fun to post them on Twitter too, and watch people overreact. To that end, the social media I use most is Twitter, @CoreyLewis86. I also contribute pieces for Forbes Wheels and Forbes Home.

More by Corey Lewis

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- SCE to AUX They're spending billions on this venture, so I hope so.Investing during a lull in the EV market seems like a smart move - "buy low, sell high" and all that.Key for Honda will be achieving high efficiency in its EVs, something not everybody can do.

- ChristianWimmer It might be overpriced for most, but probably not for the affluent city-dwellers who these are targeted at - we have tons of them in Munich where I live so I “get it”. I just think these look so terribly cheap and weird from a design POV.

- NotMyCircusNotMyMonkeys so many people here fellating musks fat sack, or hodling the baggies for TSLA. which are you?

- Kwik_Shift_Pro4X Canadians are able to win?

- Doc423 More over-priced, unreliable garbage from Mini Cooper/BMW.

Comments

Join the conversation

Fortunately Crosley's homes were restored and saved from the wrecking ball. There are so many of these grand palatial homes that went into disrepair and that were torn down. The cost to maintain homes like these becomes so expensive and they become too expensive to repair and restore. There are some videos on You Tube of many large homes some built in the last 20 years that have been abandoned and facing demolition many of these homes have nothing wrong with them and are move in ready but they are just too big and too expensive to maintain. Today we have the McMansions on lots they barely fit on which makes me wonder if a some point in the future many of these homes could be torn down.

WLW radio station is where Doris Day got her start singing with a big band live. The reception was so strong that WLW could be picked up from the jungles of Africa and in many other countries.

As I worked for WLW's then licensee, Jacor Communications, I was there with a Crosley - actually at Midnight, January 1, 2000, the engineers in Mason fired up WLW's original, water-cooled 50,000 watt transmitter, a Western Electric, and ran it for a full half-hour. Installed in 1927, it was still licensed for use at the (supposed) turn of the century. And frankly, it sounded great!