Rare Rides Icons: Lamborghini's Front-Engine Grand Touring Coupes (Part XII)

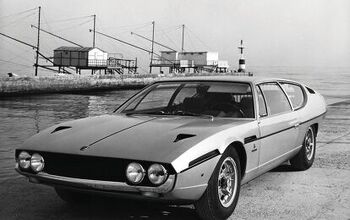

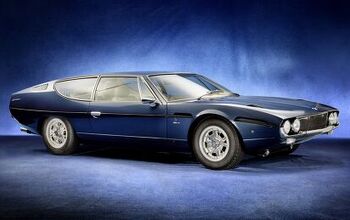

Ferruccio Lamborghini finally realized his dream of a proper four-seat grand touring coupe with the introduction of the Espada in 1968. The Espada entered production after a long and difficult styling process, which occurred simultaneously with a long and difficult engineering process. After multiple restyling attempts (and the use of a canned Jaguar coupe design), the Espada was produced in its Series I format from March 1968 to November 1969.

And while the Espada wowed at auto shows and proved there was a market for the type of upscale coupe Lamborghini envisioned, all was not well on the engineering front. Remember when Ferruccio allowed his engineers to build the TP400 chassis as a road-going racer? It turned out that deception would come back to bite him.

Lamborghini’s engineers wanted to build a race car that was usable on the road. Lamborghini didn’t think such a car was marketable, and also felt the idea was out of alignment with his vision for an upmarket sports car and a similar four-seater GT. He also had no intention of entering motorsport to compete against Ferrari, which was similarly out of alignment with the vision of his engineers.

But Ferruccio allowed Gian Paolo Dallara, Paolo Stanzani, and Bob Wallace to go on with the race car chassis anyway. The resulting TP400 was very stiff and super low to the ground, and it had to be revised and softened a bit for Miura usage. Then it had to be reworked entirely (with its engine moved to the front) for Espada duty.

A few months after the spring debut of the Espada, in August 1968, Gian Paolo Dallara (1936-) reached a breaking point with Ferruccio. Mr. Lamborghini steadfastly refused to participate in motorsport, even when the company had a chassis that was ready to do so on a moment’s notice. Further, even though the outlandish Gandini-penned Marzal was a hit upon its debut, Ferruccio didn’t want to keep making concept cars either.

Now the company had found success with the Miura and Espada, they didn’t need such PR stunts that did not result in real cars. Lamborghini kept his focus on practicality, and said “I wish to built GT cars without deficits - quite normal, conventional but perfect - not a technical bomb.”

What did Lamborghini mean by that statement? He wanted his brand to have illustrious credibility that met or exceeded that of Ferrari. And to Ferruccio’s mind, that didn't have anything to do with participating in motorsport. Disillusioned, Dallara left the company and went to work for De Tomaso and its Formula One program.

Paolo Stanzani, who was previously Dallara’s right-hand man, took over as Lamborghini’s technical director. The loss of Dallara’s chassis expertise was considerable, as he’d been with the company since its foundation. Unfortunately, his departure was not the only big hit Lamborghini took in 1969, as Series I Espada production headed toward its end.

Other troubles came from Lamborghini’s factory workers. In a classic moment of Italian industry versus its unions, Lamborghini’s fabricators and machinists were involved in a larger national workforce problem. There was a nationwide campaign started by the Italian metal worker’s union against all industries with which it was involved. The plan included sticking it to the industry by having workers enact one-hour work stoppages at random.

Lamborghini proved an invaluable leader at the moment and went down to work in the factory alongside his employees. With personal attention, he was able to keep the line going in its assembly of the various Miuras, Espadas, and the last of the Isleros. There was already an Islero replacement in the works, and we’ll save that model for a future installment.

In December of 1969, the Series II Espada began its production. The model was given a new name that nobody used: 400 GTE Espada. Much like the edits that happened during the production of Series I, the Series II revisions were aimed at improving the Espada’s livability and driving experience.

When it first debuted at the 1970 Brussels Motor Show, the Series II showed off some further improvements to engineering. Most notably, the 3.9-liter V12 had a power upgrade from 325 horses to 350, though the engine had to rev to 7,500 RPM to get that figure instead of the previous version’s 6,500 RPM. The revamped engine power (achieved via a new 10.7:1 compression ratio) made its way to all three Lamborghini models that year, as the company was interested in building only one engine at a time.

Elsewhere there were additional braking upgrades. The Series II kept the final ventilated discs of the Series I but upgraded stopping power via a revised brake booster. The suspension was different too, with stiffer springs than the Series I. Lamborghini wanted a bit better handling to the detriment of ride quality. CV joints were also implemented at the rear drive shaft in Series II.

Customers would likely forgive the Espada’s stiffer ride when they noticed power steering was newly available (as an optional extra). Worth noting, it was occasionally possible to get power steering on a Series I Espada, but it was only offered at certain times and was never an official option in the brochure. Another new feature indoors included better fresh air flow for rear passengers - an element of passenger comfort that Ferruccio found very important.

Before we cover the revised interior and exterior styling of the Series II, it’s time for a disclaimer. Because of the unique way Lamborghini was funded and the labor and parts conditions in Italy in the late Sixties and early Seventies, the Espada was often built with a “here’s what we have” approach. Series I to III of the Espada were only confined to certain timelines in theory.

For example, it was possible for a Series II to have Series I parts, or for a Series III feature to appear on a Series II car. As in the aforementioned power steering, some Series I cars were equipped with it as an off-menu option. If there was a part leftover from an old Series, or a current part ran out during production, Lamborghini would often switch to something else on the shelf.

But we’ll stop there for today, and pick up next time with the visual changes that (usually) occurred in the Series II Espada. Then we’ll take a look at a very special handful of super luxurious Espadas that began in Series II, and seem almost forgotten today. Until next time.

[Images: Dealer]

Become a TTAC insider. Get the latest news, features, TTAC takes, and everything else that gets to The Truth About Cars first by subscribing to our newsletter.

Interested in lots of cars and their various historical contexts. Started writing articles for TTAC in late 2016, when my first posts were QOTDs. From there I started a few new series like Rare Rides, Buy/Drive/Burn, Abandoned History, and most recently Rare Rides Icons. Operating from a home base in Cincinnati, Ohio, a relative auto journalist dead zone. Many of my articles are prompted by something I'll see on social media that sparks my interest and causes me to research. Finding articles and information from the early days of the internet and beyond that covers the little details lost to time: trim packages, color and wheel choices, interior fabrics. Beyond those, I'm fascinated by automotive industry experiments, both failures and successes. Lately I've taken an interest in AI, and generating "what if" type images for car models long dead. Reincarnating a modern Toyota Paseo, Lincoln Mark IX, or Isuzu Trooper through a text prompt is fun. Fun to post them on Twitter too, and watch people overreact. To that end, the social media I use most is Twitter, @CoreyLewis86. I also contribute pieces for Forbes Wheels and Forbes Home.

More by Corey Lewis

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- ToolGuy I watched the video. Not sure those are real people.

- ToolGuy "This car does mean a lot to me, so I care more about it going to a good home than I do about the final sale price."• This is exactly what my new vehicle dealership says.

- Redapple2 4 Keys to a Safe, Modern, Prosperous Society1 Cheap Energy2 Meritocracy. The best person gets the job. Regardless.3 Free Speech. Fair and strong press.4 Law and Order. Do a crime. Get punished.One large group is damaging the above 4. The other party holds them as key. You are Iran or Zimbabwe without them.

- Alan Where's Earnest? TX? NM? AR? Must be a new Tesla plant the Earnest plant.

- Alan Change will occur and a sloppy transition to a more environmentally friendly society will occur. There will be plenty of screaming and kicking in the process.I don't know why certain individuals keep on touting that what is put forward will occur. It's all talk and BS, but the transition will occur eventually.This conversation is no different to union demands, does the union always get what they want, or a portion of their demands? Green ideas will be put forward to discuss and debate and an outcome will be had.Hydrogen is the only logical form of renewable energy to power transport in the future. Why? Like oil the materials to manufacture batteries is limited.

Comments

Join the conversation

1968 Espada top speed: 152 mph.

2005 Avalon top speed: 149 mph.

Since neither of those speeds is happening in 2022 with me behind the wheel (I don't live in Ohio), I'm keeping my current car.

Ahhh a time before bumpers...its regrettable that our collective brainpower couldn't delineate which of our vehicular appliances ought to have these practical appendages and which ones definitely shouldn't.