A Selective History of Captive Minitrucks, Part One: When America Couldn't Compete

I was having a conversation with a female friend a few weeks ago and she admitted to having “fooled around” in no fewer than four different brands of minitrucks during the Nineties and Oughties. I suppose in her case that would be the Noughties — but that’s besides the point. I should also mention that the fourth “minitruck” was really a Colorado, and the incident in question happened fairly recently.

“There’s always some kind of stick shift in the way, in those little trucks, you know?” she said.

“Those are the little crosses that empowered young women have to bear,” was my response.

The conversation could have gone in any number of directions from there, but where it actually went was to A Brief Discussion Of Mini-Trucks In America, 1970-2010. I thought it might be a conversation worth having with all of you, as well, because it showcases a rather unique phenomenon in American automotive history.

Much has been written about Detroit’s inability or unwillingness to take the Japanese competition seriously, but it’s worth noting that Detroit’s dealers, particularly on the coasts, didn’t share in that consensual illusion. They could clearly see the value and utility in the first generation of Japanese minitrucks to hit these shores, and they were demanding action as early as the mid-Sixties. While GM and Ford had their subcompact cars in the pipeline, there wasn’t any equivalent plan to provide home-built compact trucks.

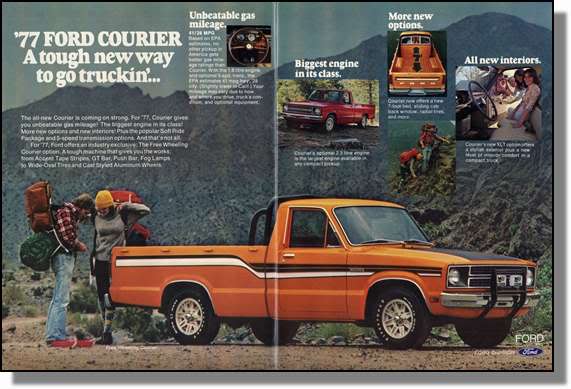

In order to keep the dealers happy, therefore, the Big 3 reached out to their various partners in Japan. Ford was first to have product on the ground, with the Courier in 1971. It was powered by a 1.8-liter inline four that developed 74 horsepower. This compared well with the first-generation Toyota truck, although once the “classic” N20 successor appeared in 1974 with its two-liter engine, the Courier could no longer keep up. It was basically a Japanese-market Mazda truck, with minor alterations.

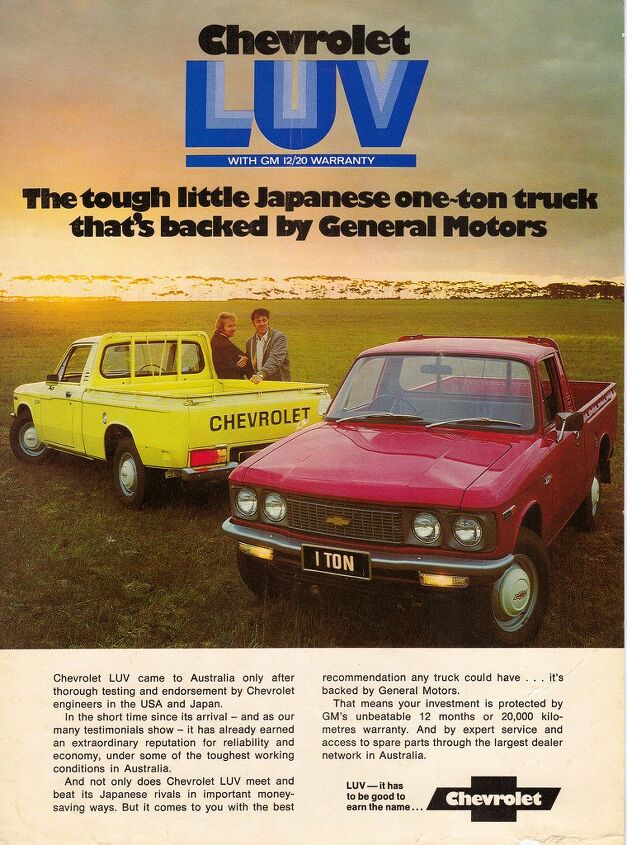

The Chevy LUV appeared the following year. There was no corresponding GMC version, perhaps because the younger buyers GM was targeting didn’t frequent GMC dealers. It was a badge-engineer job of the home-market Isuzu truck, fortified with a million tape-and-stripe packages to appeal to California surfers and dirt-bike racers. It sold anywhere from 60,000 to 100,000 units a year; not enough to significantly upset the market one way or another, but it kept close to a million buyers in a customer relationship with Chevrolet dealerships instead of letting them cross over to the Toyota shop from whence they would likely never return.

The LUV, like many other Japanese-built compact trucks, came across the ocean most of the time as a cab-and-chassis, for purposes of dodging the 25-percent “chicken tax”. It was reassembled once it reached the port in a fashion similar to the way that cargo-spec Transit Connects arrived in this country with seats installed, said seats being removed after the fact. At the time, there was much lore about “Japanese beds” and “American beds” in the minitrucking community. “Japanese beds” were single-wall affairs with rolled edges and, sometimes, cargo hooks welded under the exterior rim. “American beds” were double-walled and supposedly much more resistant to rust.

The reality of it was that only Toyota, to my knowledge, ever installed “Japanese” and “American” beds at the same time. Everybody else stuck with a Japanese-made bed. All of them rusted like hell wouldn’t have it. Outside the coasts, Japanese pickups might run forever but they didn’t last forever. It was common for the single-wall beds to rust through before the last payment was made. There was a brisk business done in acid-dipping Japanese truck beds so they could be Bondo-ed and repainted.

Four-speed manuals were the most common transmission, with five-speeds coming on stream right before the second generation of the captive trucks appeared in the late Seventies. Ford beat GM by four years this time, the squared-off Courier appearing in 1977 and the new LUV in 1981. The new Courier was considerably ahead of everybody, style-wise, but by then Ford understood the benefits of having a homegrown compact pickup and was already in development with what would become the Ranger.

The same was even more true for GM, which introduced its revised LUV just a year ahead of the domestically-produced S-10. But just as two of the Big 3 were leaving the import-pickup game, Chrysler was stepping in with a variant of Mitsubishi’s brand-new first-generation compact truck. Sold as the Dodge D50 and Plymouth Arrow, the captive Chrysler was stylistically halfway between the original LUV and the squared-off successor. This was despite the fact that Chrysler was about to follow Volkswagen’s lead in building a very light-duty pickup from its Omni/024 chassis.

As a driving proposition, however, it was far and away superior to the rest of the field. Your humble author had some wheel time in nearly all of the era’s compact trucks, regrettably in more of a McJob capacity than a making-out-across-the-bench capacity, and I can attest that the Arrow truck was a Corvette in a field of Chevelles. The five-speed was positively car-like: light effort, short throw. The brakes were sharp, and the motor liked to rev. Most importantly, the seating position was low, close to what you’d get from a Seventies Arrow compact.

It’s interesting, in retrospect, to consider just how different all the captive trucks were. The Ford was the most “truck-like”, the LUV was the flimsiest, and the Arrow was the sports car of the group. All of them were much more like compact cars than the Ranger or S-10 that would succeed them. Those first-gen American minitrucks aped the ponderous, upright nature of their full-size showroom mates, even though they were much closer in dimensions to the Japanese trucks with which they competed.

Again, having driven the S-10 and Ranger of the era when they were new, it’s difficult to overstate just how much less enjoyable they were to steer and operate than their Japanese captive predecessors. As a parts driver for my local BMW dealership, I had the choice every day of a ’79 Arrow or an ’83 Ranger, as long as I got to the shop before my fellow parts driver did. I made sure to be early every day because the Arrow was a pleasure and the Ranger was a chore.

It was an era where few of the available choices had over a hundred horsepower, tires were narrow, and accommodations were cramped. Air conditioning was a rare option. While these trucks were reliable by the standards of the era, they were chock-full of untrustworthy blower motors and instrument panels and ignition systems. Yet they were a joy to drive in a way that few modern cars can approach. They had light back ends and stick axles and there was very little insulation between the driver and the road. A lot of people chose them over the front-wheel-drive compacts of the day because they were the cheapest and closest thing a budget-minded buyer could get to a sporting vehicle.

They just weren’t very good at being substitutes for full-sized trucks. Which brings us to Part 2 of this story, in which we answer the question: Just how much farther could you go in a Colorado than you could in a Courier?

More by Jack Baruth

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Theflyersfan I used to love the 7-series. One of those aspirational luxury cars. And then I parked right next to one of the new ones just over the weekend. And that love went away. Honestly, if this is what the Chinese market thinks is luxury, let them have it. Because, and I'll be reserved here, this is one butt-ugly, mutha f'n, unholy trainwreck of a design. There has to be an excellent car under all of the grotesque and overdone bodywork. What were they thinking? Luxury is a feeling. It's the soft leather seats. It's the solid door thunk. It's groundbreaking engineering (that hopefully holds up.) It's a presence that oozes "I have arrived," not screaming "LOOK AT ME EVERYONE!!!" The latter is the yahoo who just won $1,000,000 off of a scratch-off and blows it on extra chrome and a dozen light bars on a new F150. It isn't six feet of screens, a dozen suspension settings that don't feel right, and no steering feel. It also isn't a design that is going to be so dated looking in five years that no one is going to want to touch it. Didn't BMW learn anything from the Bangle-butt backlash of 2002?

- Theflyersfan Honda, Toyota, Nissan, Hyundai, and Kia still don't seem to have a problem moving sedans off of the lot. I also see more than a few new 3-series, C-classes and A4s as well showing the Germans can sell the expensive ones. Sales might be down compared to 10-15 years ago, but hundreds of thousands of sales in the US alone isn't anything to sneeze at. What we've had is the thinning of the herd. The crap sedans have exited stage left. And GM has let the Malibu sit and rot on the vine for so long that this was bound to happen. And it bears repeating - auto trends go in cycles. Many times the cars purchased by the next generation aren't the ones their parents and grandparents bought. Who's to say that in 10 years, CUVs are going to be seen at that generation's minivans and no one wants to touch them? The Japanese and Koreans will welcome those buyers back to their full lineups while GM, Ford, and whatever remains of what was Chrysler/Dodge will be back in front of Congress pleading poverty.

- Corey Lewis It's not competitive against others in the class, as my review discussed. https://www.thetruthaboutcars.com/cars/chevrolet/rental-review-the-2023-chevrolet-malibu-last-domestic-midsize-standing-44502760

- Turbo Is Black Magic My wife had one of these back in 06, did a ton of work to it… supercharger, full exhaust, full suspension.. it was a blast to drive even though it was still hilariously slow. Great for drive in nights, open the hatch fold the seats flat and just relax.Also this thing is a great example of how far we have come in crash safety even since just 2005… go look at these old crash tests now and I cringe at what a modern electric tank would do to this thing.

- MaintenanceCosts Whenever the topic of the xB comes up…Me: "The style is fun. The combination of the box shape and the aggressive detailing is very JDM."Wife: "Those are ghetto."Me: "They're smaller than a Corolla outside and have the space of a RAV4 inside."Wife: "Those are ghetto."Me: "They're kind of fun to drive with a stick."Wife: "Those are ghetto."It's one of a few cars (including its fellow box, the Ford Flex) on which we will just never see eye to eye.

Comments

Join the conversation

If I were you I would plan on keeping the Ranger for many many years. Low miles and A-1 condition it should last you a long time. It will be many years if ever before any of the manufacturers introduce a true compact size truck and if they do it will most likely be front wheel drive base on an existing cuv. My S-10 is almost 17 years old with 106k of well maintained miles. You might as well use what you have. It is amazing how many old Rangers, S-10s, and Tacomas I see on the road. The salt and road chemicals eventually get most of them (the tin worm) but in a warmer climate that would not be an issue.

When I am finished with my S-10 it will either be donated to a high school to be used to train aspiring mechanics or go directly to the salvage yard. I will eventually get down to two vehicles.