Buy/Drive/Burn: Compact and Captive Pickup Trucks From 1982

In the last edition of Buy/Drive/Burn we pitted three compact pickup trucks from Japan against one another. The year was 1972 — still fairly early in Japan’s truck presence on North American shores. The distant year caused many commenters to shout “We are young!” and then claim a lack of familiarity.

Fine! Today we’ll move it forward a decade, and talk trucks in 1982.

All of today’s trucks have one thing in common: They’re Japanese and wear domestic branding. The Big Three was caught out by the big Japanese players’ small trucks, so its members turned to second-tier Japanese manufacturers and created captive imports. That bought some time while Ford, GM, and Chrysler worked behind the scenes to develop their own compact offerings.

In 1982, the small truck captive import party was about over.

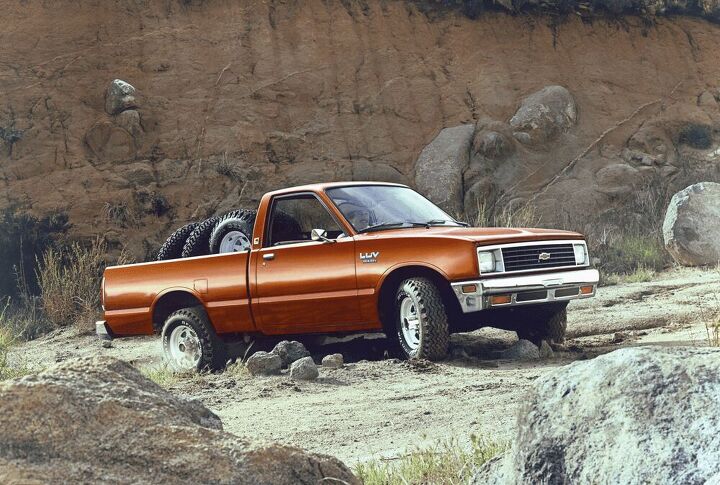

Chevrolet LUV

General Motors offered Isuzu’s Faster as the LUV between 1972 and 1982. Feeling the heat from Datsun, Toyota, and Ford (see below), the LUV started out with an inline-four of 75 horsepower as its only engine offering. A facelift in 1974 was followed with an automatic transmission offering in 1976, and four-wheel drive (the first on a compact truck) in 1979. 1981 brought the arrival of a second-generation LUV, though Isuzu renamed the truck Pick Up in other markets. More power was finally available, too. Today’s engine is the largest 2.3-liter four, paired to a manual transmission and 4×4.

LUV was replaced in 1983 by the S-10.

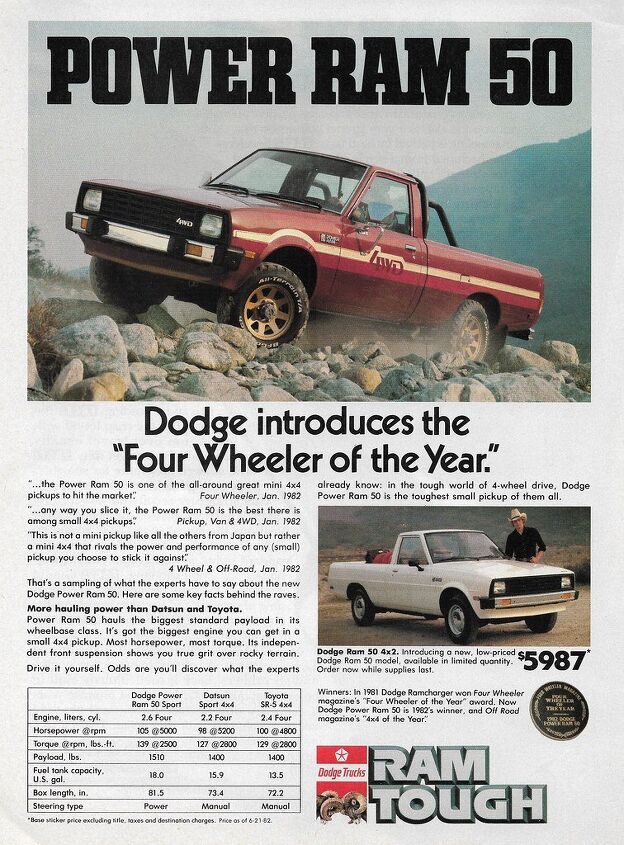

Dodge Ram 50

Dodge was late to the game with its small truck offering, introducing the new D-50 in 1979. Underneath the logos was the first-generation Mitsubishi Triton, or Mighty Max if it feels more comfortable. The name switched to Ram 50 in 1981, and it was sold alongside its twin, the Plymouth Arrow. 1982 was a year of change for the Ram 50: The Arrow went away as Mitsubishi offered the Mighty Max under its badge for the first time. Meanwhile, four-wheel drive became available. Said versions carried the Power Ram 50 moniker. The largest gasoline engine available (and our pick today) was the 2.6-liter four-cylinder from other Mitsubishi truck products.

Today’s Power Ram 50 is also paired with a five-speed manual. Though Chrysler introduced the Dakota as the Ram 50’s replacement in 1987, it continued to sell both trucks together through 1994.

Ford Courier

Ford hired Mazda to import its gen two B-Series truck, then sold it through its North American dealerships starting in 1972. Its first iteration was saddled with a 1.8-liter engine of 74 horsepower, mated to a four-speed manual or three-speed automatic. Ford wasn’t sure how to badge the Courier, switching placement and names three or four times in the first generation. A second gen debuted in 1977 and carried notable upgrades in power and drivability. The base engine was enlarged to two full liters, and disc brakes appeared at the front. Optional was a 2.3-liter Pinto engine. Critically, the Courier was never available with four-wheel drive. That means today’s Courier pairs the larger Pinto engine with a five-speed manual and 4×2. The Ranger was ready for 1983, though Ford and Mazda’s truck times were far from over.

Three compact captives, two of them on their deathbeds in 1982. Which is worth a Buy?

[Images: Ford, GM, Dodge]

Interested in lots of cars and their various historical contexts. Started writing articles for TTAC in late 2016, when my first posts were QOTDs. From there I started a few new series like Rare Rides, Buy/Drive/Burn, Abandoned History, and most recently Rare Rides Icons. Operating from a home base in Cincinnati, Ohio, a relative auto journalist dead zone. Many of my articles are prompted by something I'll see on social media that sparks my interest and causes me to research. Finding articles and information from the early days of the internet and beyond that covers the little details lost to time: trim packages, color and wheel choices, interior fabrics. Beyond those, I'm fascinated by automotive industry experiments, both failures and successes. Lately I've taken an interest in AI, and generating "what if" type images for car models long dead. Reincarnating a modern Toyota Paseo, Lincoln Mark IX, or Isuzu Trooper through a text prompt is fun. Fun to post them on Twitter too, and watch people overreact. To that end, the social media I use most is Twitter, @CoreyLewis86. I also contribute pieces for Forbes Wheels and Forbes Home.

More by Corey Lewis

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Ajla My only experience with this final version of the Malibu was a lady in her 70s literally crying to me about having one as a loaner while her Equinox got its engine replaced under warranty. The problem was that she could not comfortably get in and out of it.

- CoastieLenn Back around 2009-2010, a friend of mine had a manual xB and we installed a Blitz supercharger kit. Was a really fun little unit after that.

- Ajla What is Chevrolet going to run in NASCAR? I get that there is basically no connection to street cars any longer but I still don't see them putting Blazer or Corvette stickers on their stuff.

- CKNSLS Sierra SLT Since they are the darling of the rental fleets I have probably spent about 5,000 miles in two different Malibus. I was ready to be discouraged. But for what they are-they are a competent riding vehicle and they get close to 40mpg cursing at a reasonable speed. A little too much plastic in the interior-making it look "cheap". But if I was looking for a competent sedan I would consider an off rental one at a decent price. A new one would suffer massive depreciation-probably.

- Arthur Dailey Kinda wish that I had bought one back in 2011. Yes I know that some here prefer the first generation to the second. But the first was not available new in Canada.I didn't appreciate the centre mounted instrument panel.However one of my children had one as a week long rental and much preferred it to the Prius that she had previously.

Comments

Join the conversation

LS swap the LUV Hemi swap the Ram Coyote/Godzilla swap the Courier

My 99 S10 that I gave to my nephew is still going strong after 21 years. Mine has the 5 speed manual with the I-4. Having a manual in a truck like this makes a huge difference compared to the automatic.