Twincharging Is Volvo's Replacement For Displacement

Engine downsizing is all the rage. Making the engine smaller increases fuel efficiency, reduces emissions and cuts vehicle weight. With ever tightening fuel economy legislation in the United States and CO2 emissions regulation in the European Union, mainline manufacturers are turning to turbochargers like never before. In 2009 just 5% of cars sold in America sported turbos, and that 5% consisted largely of European brands like Volvo and BMW with a long history of forced induction. By 2013 that number had more than doubled to 13%. Honeywell expects the number to rise to 25% in the next four years and the EPA tells me that by 2025 they expect 90% of cars sold in America to sport a turbo engine. With turbos becoming so ordinary, what’s a turbo pioneer like Volvo do to keep a competitive edge? Add a supercharger of course.

I recently had the opportunity to sample the new Volvo V60 (expect a first drive review shortly) but the star of the show wasn’t the car itself, it’s what’s under the hood. New engine designs are truly a rarity in the automotive world with engines being tweaked over time to keep them fresh. Volvo’s own modular engine found under the hood of most Swedish cars (and the occasional Focus RS) turned 24 years old this year, but it’s a spring chicken compared to the Rolls Royce L series 6.75L engine that dates back to 1952. Being the engine nerd I am, I spent a new hours with Volvo’s powertrain engineer discussing their new “Drive E” engine family.

Volvo’s new engine family is primarily a clean sheet design, although many design components are descendants of the old “modular” engine family. The line consists of four different variants dubbed T3, T4, T5 and T6. As before, T indicates turbocharged but now the number represents power output rather than the number of cylinders involved. Yes, this is the death knell for Volvo’s funky 5-cylinder because this is a strict four-cylinder lineup. Volvo has said the 149 horsepower T3 and the 188 horsepower T4 won’t be headed to America at the moment, so don’t expect to see a direct competitor for BMW’s downsized 320i from Sweden this year. Instead we get the 241 horsepower T5 and the 302 horsepower T6 under the hood of everything except the XC90.

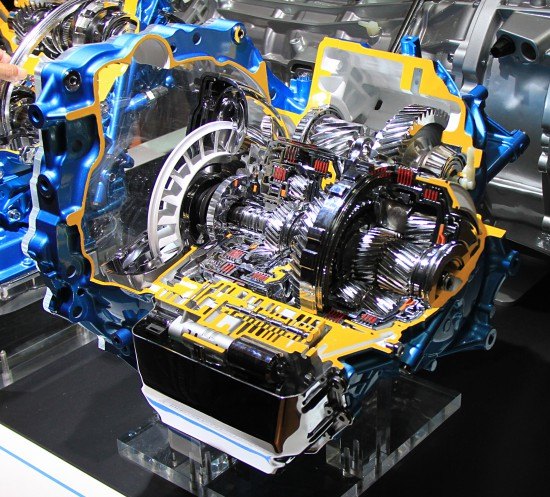

All engines share a common block design, but what changes is the boost. T3, T4 and T5 engines use a single turbo while T6 adds a Roots-type supercharger in addition to the turbocharger. VW and others have dabbled with twincharging in the past, with VW’s 1.4L twincharged engine finding a home under the hoods of Euro models and putting down 140-180 horsepower. Volvo is taking things to the next step by calling their 2.0L engine the replacement for not just the 3.0L twin-scroll turbo but also the recently departed 4.4L V8.

While supercharging and turbocharging sounds excessive, there is a logic to the madness. While peak torque on the turbo-only T5 just 15 lb-ft lower than the T6 (when in overboost), the supercharger allows the T6 to deliver approximately 140 lb-ft more torque just off idle. The torque curves converge around 1,500-1,600 RPM when the T6 switches over to the turbocharger. From approximately 2,000 RPM to 3,500 RPM torque remains flat on both engines but the larger turbo on the T6 allows it to maintain peak torque all the way past 4,500 RPM. When torque does start to wane it does so more gradually than turbo-only engines.

Why not stick with a supercharger alone like Jaguar and other auto makers? The reason is two-fold. Turbochargers operate off of “waste energy” from the exhaust. Exhaust gases spin the turbine which in turn spins the compressor forcing more air into the engine. In truth “waste energy” is a misnomer because there is a horsepower toll for having the turbo interfering with the exhaust stream, but in general this toll is smaller than the power required to operate a supercharger. The downside to a turbo is well known: turbo lag. Turbo lag is the time it takes the turbo to start “boosting.” Although the turbo is spinning at idle, it’s creating little positive pressure. Step on the gas and it takes a while for things to start humming along and boost to be created. That’s why the T5 has a lower torque rating off idle.

Superchargers are typically driven off the accessory belt. Because of the “direct” connection to the engine, they are always creating boost. Because this boost happens in sync with engine RPMs, the response is immediate. On the down side superchargers can consume up to 20% of an engine’s total power output according to Honeywell. This is considered a good trade since they can boot power up to 50%. Because of design trade offs, factory supercharged engines tend to “run out of breath” at higher RPMs which explains why Jaguar’s 5.0L supercharged engine lags the 4.4L and 4.7L twin-turbo German engines by a wide margin in peak torque.

Volvo’s answer to both problems was to use a supercharger for immediate response at the low end. From idle air flows into the supercharger then through the turbo into the engine. This not only improves low end response but it also helps get the turbo up to speed faster. At some point determined by the car’s computer (around 3,500 RPM) the engine opens a butterfly valve to bypass the supercharger and then de-clutches the supercharger to eliminate the inherent loss. This process allows a supercharger tuned for low end response and a turbo tuned for higher RPM running to be joined to the same engine. The result is a horsepower and torque curve superior to Volvo or BMW’s 3.0L twin-scroll turbos in every way, from torque at idle, length of the torque plateau, to high-RPM torque. To further increase efficiency Volvo relies on a variable speed electric water pump for cooling, direct-injection for combustion efficiency and low friction bearings and rings. Volvo’s marketing literature hails this as the answer to the V8.

But is it really? Yes and no. The pint-sized engine allows the XC60 to deliver 29 MPG on the highway in 304 horsepower T6 trim which is a 50% increase over Volvo’s 2009 XC90 V8. Score one for Drive-E. Out on the road, the 2.0L engine delivers more low end torque than any other 2.0L four-banger sold in America giving the XC60 more punch off idle than I expected. The T6’s torque curve may be flatter than Volvo’s sort lived 4.4L V8, but it’s not quite as robust at the top end or at idle. The broad torque band and the Aisin 8-speed auto allowed the XC60 T6 to tie an XC90 V8 to 60 MPH. Aurally, Volvo’s “burbly” V8 is the clear winner. The Drive-E engine has a distinct (but muted) supercharger whine under 3,500, a definite four-cylinder exhaust note and an eerie silence at idle. Volvo was cagey about any Polestar tunes for their new engine, but I suspect considerable work will need to be done to best Volvo’s own Polestar I6.

My inner engineer is excited by the possibilities of modern forced induction technologies and small displacement engines. I suspect that the vast majority of American shoppers would be hard pressed to notice the difference between Volvo’s twin-charged 2.0L engine and a V8 in the 4L range in terms of power delivery and drive-ability. The constant march towards fuel economy also fills me with sadness. No matter how you slice it, a naturally aspirated V8 has a sound that we’ve grown up associating with performance and luxury. This association is so strong that BMW pipes V8 sounds into the cabins of their turbo V8s because the turbos interfere with the exhaust notes. As our pocketbooks rejoice, join me as I shed a tear for the naturally aspirated inline-6 and V8.

More by Alex L. Dykes

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Lou_BC Well, I'd be impressed if this was in a ZR2. LOL

- Lou_BC This is my shocked face 😲 Hope formatting doesn't fook this up LOL

- Lou_BC Junior? Would that be a Beta Romeo?

- Lou_BC Gotta fix that formatting problem. What a pile of bullsh!t. Are longer posts costing TTAC money? FOOK

- Lou_BC 1.Honda: 6,334,825 vehicles potentially affected2.Ford: 6,152,6143.Kia America: 3,110,4474.Chrysler: 2,732,3985.General Motors: 2,021,0336.Nissan North America: 1,804,4437.Mercedes-Benz USA: 478,1738.Volkswagen Group of America: 453,7639.BMW of North America: 340,24910.Daimler Trucks North America: 261,959

Comments

Join the conversation

The whole idea of twin charging seems silly to me when twin scroll turbochargers have virtually eliminated turbo lag. Anyone who has driven a modern turbocharged car with a twin scroll turbo set up knows just how quickly they build boost. So why even bother with twin charging at all?

small displacement 4 banger super and twin turbo charged to within in inch of its life? Still better than a hybrid. I'm in.