Racing in the Rain: The Undoing of LoPatin's Raceway Dreams

After a weekend of rain for this year’s running of the Chevrolet Detroit Belle Isle Grand Prix, critics questioned IndyCar and the CDBIGP honcho Roger Penske’s decision to schedule the race event in late May, making it the first race in the schedule after the series’ marquee event, the Indy 500. While in most recent years the racing at Belle Isle has experienced picture postcard worthy sunny skies, holding a race on an island during late spring in the Great Lakes region will always carry some risk of rain. Penske should know that. It was bad weather experienced by another racing promoter that resulted in Penske acquiring what would become one of the more successful business enterprises of his exceptionally successful career.

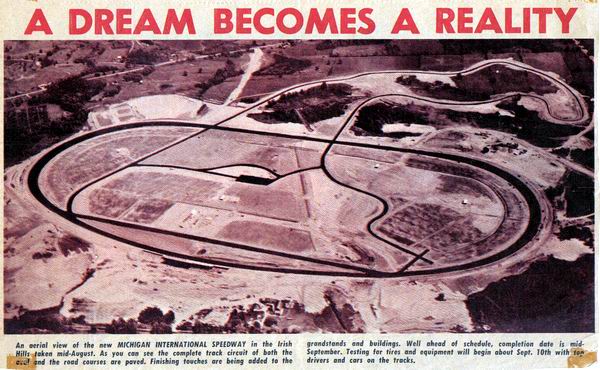

About 90 miles west of Belle Isle, in what travel guides usually call “the picturesque” Irish Hills, is Michigan International Speedway. MIS, or Michigan International Raceway as it has sometimes been called, was the brainchild of a Detroit-area lawyer and developer named Larry LoPatin. LoPatin had a good idea, a national network of modern, fan-friendly racetracks, but ran into a string of just about the worst weather a promoter of outdoor events could experience.

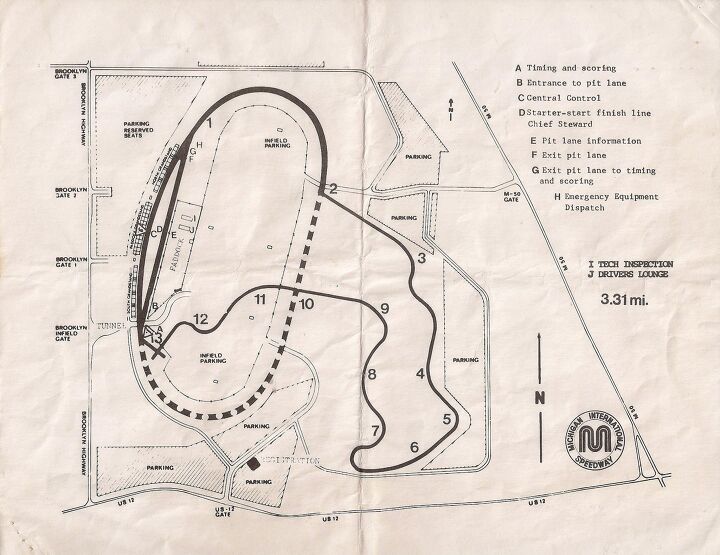

Groundbreaking for the 1,400 acre site began in the fall of 1967. Reports estimate that LoPatin and his backers put between $4 and $6 million into initial construction of the facility. LoPatin hired Charles Moneypenny, also responsible for the high banked Daytona International Speedway, to lay out the D-shaped 2 mile oval with its 18° banking in the turns, 12° banks on the arcing front straight and 5° on the backstretch. A road course, designed with the input of Stirling Moss, was also constructed with a couple of configurations that included the oval’s infield and a section of the course that ran outside the perimeter of the oval.

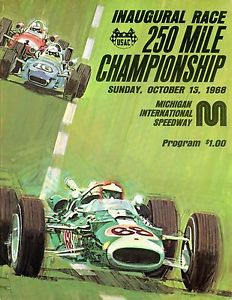

LoPatin originally tried to locate the track closer to Detroit so he could lease the facility to car companies for testing in addition to holding races, but had difficulty finding a welcoming municipality and settled on the more rural location. LoPatin then hoped putting it 90 miles closer to Chicago would draw some racing fans from Illinois to offset those Detroiters not willing to make the drive. Indianapolis, Cleveland and Toronto were also potential markets. He made deals with NASCAR for stock car racing, hoping to introduce the north to what had been a regional sport in the southeast, as well as for open wheel racers with USAC, which ran the Indy 500. The inaugural USAC race in October of 1968 had a purse that was second only to the Indianapolis race. MIS’ first NASCAR race in June of the following year featured a door-banging, wall-scraping battle between LeeRoy Yarbrough and eventual winner Cale Yarborough, driving for the Wood Brothers.

Having hosted successful events with America’s top two racing series, MIS was making money and LoPatin went forward with what some considered a grandiose plan: a nationwide network of racetracks. Time (and Humpy Wheeler, the France family, and Mr. Penske) has proven that concept to have been worthy. He established a company called American Raceways Incorporated and built a copy of MIS called the Texas World Speedway. ARI bought a 47 percent interest in the road course at Riverside, California, a 19 percent stake in the Atlanta Motor Speedway with an option to take a controlling interest, and an all-new track was planned for New Jersey, where ARI bought 600 acres of land, to serve the New York City market.

Things were figuratively looking sunny for Larry LoPatin and American Raceways Incorporated but there were some literal storm clouds threatening.

The bad weather started with the opening race of 1969, MIS’ second race. The Wolverine Trans-Am was the opening race for the 1969 Trans-Am series that featured American pony cars like the Boss 302 Mustang. It didn’t just rain. It was cold enough for snow and sleet. Some cars that went off the road course got stuck in mud. One car hit spectators, injuring several and killing one.

Later that year, bad weather at Atlanta and Riverside caused postponements and washouts of races at those tracks. A planned 600 mile race at MIS was run half under caution due to rain, then red flagged and called due to darkness at just 330 miles. At NASCAR’s season ending Texas 500 in December, less than 23,000 fans showed up.

Weather wasn’t the only problem that LoPatin faced in 1969. A dispute with USAC kept the popular Indy cars off the MIS track that year.

1970 wasn’t any better. The spring race at the Atlanta track was washed out and rescheduled for the following Sunday, which coincidentally was Easter, resulting in ticket refunds and even fewer attendees than the December race in Texas. It’s not clear if weather was a factor, but the two races that year at Riverside drew small crowds. ARI cancelled a race in June at the Texas track, citing a labor strike at Goodyear’s facility that made racing tires, but it was more likely due to poor advance sales.

If weather and poor ticket sales weren’t bad enough, LoPatin reportedly got into an argument with Bill France Sr over the size of the purse for the December NASCAR race in Texas. That dispute was likely less about the size of the purse than the fact that France, who then controlled just two tracks, Daytona and his new venture at Talladega, saw LoPatin as a competitive threat.

With bad weather and poor gates, revenue dropped. ARI missed a loan payment on the Texas track and failed to post the prize money for the August race at Atlanta. Worried about his management of the company and rapid overexpansion, the stockholders stepped in and fired LoPatin. In 1971, ARI tried to reorganize under bankruptcy provisions, allowing racing events and testing sessions to continue that year, but the company went into receivership the following year.

At a 1973 auction, Roger Penske bid $2 million for Michigan International Raceway. He’d been running American Motor’s racing teams and had a commitment from AMC for leasing the facility for testing. With that revenue guaranteed, Penske began a program of expanding and improving MIS. Over the next 25 years, it became one of the finest (and fastest) racing venues in North America. The last road race at the facility was held in 1984, but the outfield road course continued to be used for testing. In recent years, the infield track has been resurfaced, upgraded and put back into use for testing, though there are no current plans to host road races.

Penske’s business team at MIS was headed by Walt Czarnecki, who had worked for Hurst Performance and later was in charge of AMC’s performance cars, including the wild SC/Rambler and “The Machine” Rebel. Czarnecki left AMC to be Penske’s partner at Roger’s first car dealership and he’s still the #2 man at Penske Corp. Roger Penske may be a billionaire today, but Czarnecki recalls how he and Penske sold tickets out of aprons at the gates for their first event at MIS. Over the years, capacity has increased fivefold from LoPatin’s 25,000 seat grandstand and garages. Luxury suites have been added along with administration and maintenance buildings.

In 1997, Roger Penske formed Penske Motorsports, a publicly traded company that controlled his racetracks and some of his racing businesses (but not the racing teams). In a bit of deja vu, the company that controlled the Michigan track then built California Speedway (a near copy of MIS), bought 45 percent of the Homestead-Miami track in Florida and the following year bought North Carolina Speedway.

Larry LoPatin’s original plan of a national group of racetracks came to fruition when Penske Motorsports was acquired in 1999 by International Speedway Corp., controlled by the France family. LoPatin himself never returned to the racing business. He continued to work in land development, dying in 1993 at the age of 63, while working on a resort development in northern Michgian. Like the racetrack he built in the Irish Hills, the real estate development company that he founded still exists.

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, a realistic perspective on cars & car culture and the original 3D car site. If you found this post worthwhile, you can get a parallax view at Cars In Depth. If the 3D thing freaks you out, don’t worry, all the photo and video players in use at the site have mono options. Thanks for reading – RJS

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, the original 3D car site.

More by Ronnie Schreiber

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- W Conrad I'm not afraid of them, but they aren't needed for everyone or everywhere. Long haul and highway driving sure, but in the city, nope.

- Jalop1991 In a manner similar to PHEV being the correct answer, I declare RPVs to be the correct answer here.We're doing it with certain aircraft; why not with cars on the ground, using hardware and tools like Telsa's "FSD" or GM's "SuperCruise" as the base?Take the local Uber driver out of the car, and put him in a professional centralized environment from where he drives me around. The system and the individual car can have awareness as well as gates, but he's responsible for the driving.Put the tech into my car, and let me buy it as needed. I need someone else to drive me home; hit the button and voila, I've hired a driver for the moment. I don't want to drive 11 hours to my vacation spot; hire the remote pilot for that. When I get there, I have my car and he's still at his normal location, piloting cars for other people.The system would allow for driver rest period, like what's required for truckers, so I might end up with multiple people driving me to the coast. I don't care. And they don't have to be physically with me, therefore they can be way cheaper.Charge taxi-type per-mile rates. For long drives, offer per-trip rates. Offer subscriptions, including miles/hours. Whatever.(And for grins, dress the remote pilots all as Johnnie.)Start this out with big rigs. Take the trucker away from the long haul driving, and let him be there for emergencies and the short haul parts of the trip.And in a manner similar to PHEVs being discredited, I fully expect to be razzed for this brilliant idea (not unlike how Alan Kay wasn't recognized until many many years later for his Dynabook vision).

- B-BodyBuick84 Not afraid of AV's as I highly doubt they will ever be %100 viable for our roads. Stop-and-go downtown city or rush hour highway traffic? I can see that, but otherwise there's simply too many variables. Bad weather conditions, faded road lines or markings, reflective surfaces with glare, etc. There's also the issue of cultural norms. About a decade ago there was actually an online test called 'The Morality Machine' one could do online where you were in control of an AV and choose what action to take when a crash was inevitable. I think something like 2.5 million people across the world participated? For example, do you hit and most likely kill the elderly couple strolling across the crosswalk or crash the vehicle into a cement barrier and almost certainly cause the death of the vehicle occupants? What if it's a parent and child? In N. America 98% of people choose to hit the elderly couple and save themselves while in Asia, the exact opposite happened where 98% choose to hit the parent and child. Why? Cultural differences. Asia puts a lot of emphasis on respecting their elderly while N. America has a culture of 'save/ protect the children'. Are these AV's going to respect that culture? Is a VW Jetta or Buick Envision AV going to have different programming depending on whether it's sold in Canada or Taiwan? how's that going to effect legislation and legal battles when a crash inevitibly does happen? These are the true barriers to mass AV adoption, and in the 10 years since that test came out, there has been zero answers or progress on this matter. So no, I'm not afraid of AV's simply because with the exception of a few specific situations, most avenues are going to prove to be a dead-end for automakers.

- Mike Bradley Autonomous cars were developed in Silicon Valley. For new products there, the standard business plan is to put a barely-functioning product on the market right away and wait for the early-adopter customers to find the flaws. That's exactly what's happened. Detroit's plan is pretty much the opposite, but Detroit isn't developing this product. That's why dealers, for instance, haven't been trained in the cars.

- Dartman https://apnews.com/article/artificial-intelligence-fighter-jets-air-force-6a1100c96a73ca9b7f41cbd6a2753fdaAutonomous/Ai is here now. The question is implementation and acceptance.

Comments

Join the conversation

While I think the current Detroit course is too tight (all "street circuits" have this problem) this weekend's races were awesome to watch on TV. Just like F1 anytime your have mixed conditions or rain the results get all jumbled up which makes things entertaining. There are lots of great tracks IRL could run. For example what happened to running Watkins Glen or Sebring? The logistics just make sense to use purpose built race tracks, they have the parking, the paddock area and all the infrastructure to support race events. Temporary street circuits no matter how good are just too much of a compromise for fast but twitchy Indy cars. St. Pete and Cleveland airports sort of work out because they are wide. However we have seen several problems with bumps and uneven surfaces resulting in accidents and injuries. I remember Brazil and Baltimore as prime examples. Now for other series that use smaller, slower road cars such tracks do make some sense.

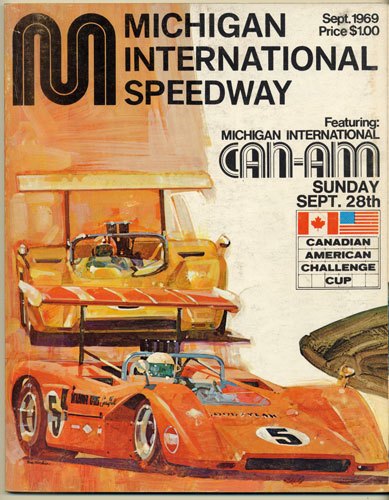

We had beautiful weather for the '69 Can-Am race. Sat outside of turn 5. Cars ran for an hour or so in the morning for practice; lots of noise. Then the pre-race parade was on track. GM cars trying to get thru the right hand turn, tires squealing, almost rolling over at what was a crawl compared to the race cars. THAT'S when we realized how damn fast the race cars were. It was the Bruce and Denny show with Dan Gurney driving one of their backup cars for third; they had to slow up on the last lap so he could catch up and have a 1-2-3 group photo at the finish. I was 17, but the college guys were building a pyramid of beer cans leaning against the fence. They had it about 7 can high and 6 feet wide by the end of the race.