It's 10:00 PM And Your Van Needs a New Gas Pedal: FrankenPedal!

The ’66 A100 Hell Project van came to me in shockingly good shape for a 44-year-old vehicle that sat dead for over a decade, but it still needed endless a few repairs before being really roadworthy.

The Hell Project A100 came to me with a hole-in-the-block-coming-soon rod-knocky 318, so the first order of business was to drop in a replacement 318 (the 273 was the only A100 V8 option in ’66, so the bad engine wasn’t the numbers-matching original unit— sorry, date-code-worshiping Mopar purists!). Then the top priority was the strange soup of former hydrocarbons in the fuel tank, with associated rust/varnish/radioactive electroplating solution clogging the rest of the fuel system (more on that later). After that? The goddamn duct tape hinge on the floor-pivoting gas pedal, which required exact foot positioning and careful movements to avoid binding up the throttle linkage while driving. Unacceptable!

The A100 has a throttle-linkage mechanism that appears to have been designed, on cocktail napkins, over shots of happy-hour well bourbon at some Keego Harbor dive. I’m picturing a trio of junior Dodge Truck Division engineers, all decked out in cheap 1962 suits and chaining unfiltered Pall Malls, looking down the barrel of a tomorrow deadline. “If I don’t have a throttle linkage design to bring to the meeting tomorrow morning,” thundered their boss, a bullneck who ground out his cigars in an ashtray made from the skull of a Japanese Navy cook he offed with his teeth on Tarawa, “You’ll be lucky to find jobs scraping the calcium deposits off the urinals at the Greyhound station!”

So, after the 11th shot of Schenley’s, our heroes came up with a design that placed the moving parts of the linkage just inside the van’s grille, where mud, debris, and the occasional walnut-sized rock pummeled it during every drive. This promotes corrosion and associated character-building frequent repairs. The end of the throttle cable (which runs back and up to the engine) faces forward, ensuring that schmutz will build up inside and lead to frequent snapped cables. Then, to top things off, there’s a finicky, knuckle-shredding arrangement of jam nuts (repeated at the carburetor end) to enhance the collection of 3/8″ wrenches in the splash pan. The upshot of all this— other than a lesson in Chrysler Corporation’s history of cheapo corner-cutting techniques dating back to what some allege were its glory days— is that any irregularity in the arc of the gas pedal’s actuation will lead to… problems.

Right. Fortunately, Chrysler’s hallowed tradition of low-bidder cheapness means that they used variations on the same bottom-hinged gas pedal theme on many of their trucks for decades, and I managed to find a similar pedal in this late-70s camper van at a well-stocked self-service Denver junkyard near my house.

I said similar, because while the overall shape and all-important metal-backed rubber hinge at the pedal’s bottom was identical to the A100’s pedal, the newer van used a Stone Age lever-sliding-on-plastic-backing-plate connection to the throttle linkage, while the A100 used a ball-and-socket/down-through-the-floor connector that must have cost 11 cents more per unit. The whole mess, in both cases, involves a Soviet-grade crude-yet-sturdy rubber-molded-around-steel construction method, no doubt stamped on a press in Indiana that stood five stories tall, shook the earth, and polluted the groundwater for generations to come.

Once I tore the duct tape off the old hinge, I identified the problem: the metal had rusted and the rubber had torn. The screw holes that mounted the pedal to the floor— using unreachable nuts on the back side, of course— had also become hopelessly enlarged. At this point, a new factor came into play: I had promised my wife that, when the first snow fell, she’d be able to park her nice Outback in the garage. Now I’d disassembled the entire throttle mechanism… and the weather report called for snow the next morning. I could just work the carburetor by hand (one of the the benefits of forward-control vans) and park the van outside that way, but I decided— at 10:00 PM, in my freezing-ass garage— to fix this now! Later, I’d find a correct pedal and replace my “temporary” installation (the usual door-hinge-on-scrap-metal method was out, because I’m doing my best to avoid cutting new holes in my relatively unmolested van’s steel).

I thought about hacking off the ball-and-socket portion of the old pedal and somehow attaching it (JB Weld? Small brackets?) to the new pedal, but that would have broken immediately. The problem is that the inherent wonkiness of the throttle linkage requires a certain amount of side-to-side flexibility, which requires a ball-and-socket linkage, so I couldn’t just rig up a new arm that permitted motion in two dimensions. Since I was doing this project tonight, with no access to junkyards or hardware stores, I couldn’t fabricate anything too complicated, anyway.

The all-important bottom hinge and screw holes in the new pedal were in excellent condition. What I needed to do was swap that part onto the old pedal’s top portion. That way I could use the original mounting holes and avoid ruining the sacred originality of the van too irrevocably. Of course, long-term I’ll be painting it in some ghastly two-tone metalflake getup and bolting 1974-vintage Sparkomatic organ-pipe speakers all over the interior, but who says logic should be used when making such decisions?

Anyway, I’ll be installing one of these soon enough, so the appearance of the gas pedal will be less important than its function.

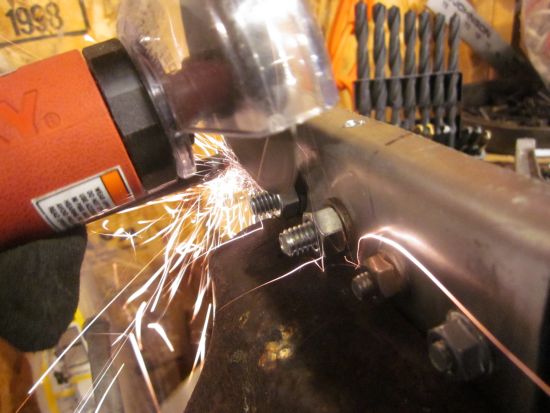

The plan: cut both pedals in half and rig up some kind of bracket to hold the halves together. Mmmm, there’s nothing like the smell of burning rubber and steel when you get to sawin’ with the cutoff tool. No, it’s not easy shooting photographs while you do this sort of thing, but I emerged from the process with all my fingers still attached.

Remember, lawsuit-minded readers, Murilee Martin says: “Always use eye protection when you cut gas pedals in half!”

Once I’ve filled the garage with vile-smelling smoke, its flavor no doubt enhanced by decades of foot-juice buildup on the pedals, the inner steel structure of the Dodge truck accelerator pedal becomes apparent.

Here’s a cross-section view. Very crude, very strong, from the era before Detroit learned how to cut every possible corner.

Next, I’ll need to fabricate some sort of bracket. My new pad’s garage isn’t wired for 220 volts yet, so there will be no welding. Cruder measures will be called for here; break out the sheet of street-sign aluminum I used for the Black Metal V8olvo’s instrument panel!

About seven seconds of crude Sharpie sketching later and I’m ready to hack away with the jigsaw. Hey, this thing needs to be done tonight! At this point I’m channeling the get-this-shit-done attitude of the drunken 1962 Dodge Truck Division engineers.

A few taps with the dead-blow hammer— a a LeMons Supreme Court bribe, courtesy of a Detroit team, by the way— and the bracket assumes its very precise configuration.

Bending the side tabs around the pedal’s bottom half to fix it in place, I drill some holes to attach bracket to pedal. Note that I’m going between the foot-juice-collecting ridges; I don’t want screw heads interfering with my ability to control tip-in with masterly acumen.

On the top half of the pedal, I use a spade bit to eat some screw-head-sized holes in the rubber, so that the screw heads will be quasi-flush with the rubber surface. Again, without a good sense of tip-in a man cannot drive his van at 11/10ths.

Meanwhile, garage tunes are provided by the Junkyard Boogaloo Turbo Boombox; since its car battery went bad, I’ve fueled it with some computer UPS gel-cells, and they require battery-charger help when the temperature drops below 40 degrees.

Two screws on each half, some more pounding of the bracket’s edge flanges to crimp them over the pedal, and the resulting assembly is quite sturdy.

Hmmm… those screws are going to hit the floor when I mash the gas… and I don’t have shorter ones in my junkyard fastener collection. What to do?

Time to go all Red Green on the offending screws! I’m sure glad I have a garage now; in the old days, I’d have done this sort of thing in the driveway. At midnight.

And there we have it: fully functioning gas pedal (though the “fully functioning” part didn’t really happen until I’d finished 45 minutes of futzing with linkage adjustments and lubrication). It looks a little odd, but just wait until the Foot Gas Pedal (with matching dimmer-switch foot) arrives!

Murilee Martin is the pen name of Phil Greden, a writer who has lived in Minnesota, California, Georgia and (now) Colorado. He has toiled at copywriting, technical writing, junkmail writing, fiction writing and now automotive writing. He has owned many terrible vehicles and some good ones. He spends a great deal of time in self-service junkyards. These days, he writes for publications including Autoweek, Autoblog, Hagerty, The Truth About Cars and Capital One.

More by Murilee Martin

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Sayahh I do not know how my car will respond to the trolley problem, but I will be held liable whatever it chooses to do or not do. When technology has reached Star Trek's Data's level of intelligence, I will trust it, so long as it has a moral/ethic/empathy chip/subroutine; I would not trust his brother Lore driving/controlling my car. Until then, I will drive it myself until I no longer can, at which time I will call a friend, a cab or a ride-share service.

- Daniel J Cx-5 lol. It's why we have one. I love hybrids but the engine in the RAV4 is just loud and obnoxious when it fires up.

- Oberkanone CX-5 diesel.

- Oberkanone Autonomous cars are afraid of us.

- Theflyersfan I always thought this gen XC90 could be compared to Mercedes' first-gen M-class. Everyone in every suburban family in every moderate-upper-class neighborhood got one and they were both a dumpster fire of quality. It's looking like Volvo finally worked out the quality issues, but that was a bad launch. And now I shall sound like every car site commenter over the last 25 years and say that Volvo all but killed their excellent line of wagons and replaced them with unreliable, overweight wagons on stilts just so some "I'll be famous on TikTok someday" mom won't be seen in a wagon or minivan dropping the rug rats off at school.

Comments

Join the conversation

HA

A '66 Dodge A-100 cargo van was my first "sin bin" back in the day. It had the 273/A727 combo.