Do You Use Any of These 'Freeways Without Futures?'

Urban transportation is a slippery fish. No two cities are the same, and most need to harmonize foot, rail, bike, bus, and automobile transportation to ensure everyone can get where they’re going in a timely manner. Unfortunately, as the constantly changing recipe varies significantly between towns, some projects can hamper a city’s wellbeing.

Take New York as an example. The city’s subway system is well on its way to becoming an unmitigated disaster as more and more disgruntled residents lean on ride-hailing services as an alternative. This has increased on-road congestion, without making the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s underground option cheaper, less crowded, or more reliable. The city has since decided to enact congestion charges for Lower Manhattan.

Other towns face similar issues, with the presiding logic frequently being little more than “let’s just cram a highway through there.” Unlike in past decades, cities are increasingly hesitant to enact such plans. An ill-placed freeway can spell disaster for local communities, just as a well-placed one can help bedroom communities thrive. Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) recently released a list of 10 highways it would like to see demolished in order to create more walkable, connected neighborhoods under the banner of promoting “great urbanism.”

While we found CNU’s “F reeways Without Futures” report fascinating — and willingly agree that highways can absolutely divide established neighborhood, sometimes sapping their growth potential — the organization’s biases are glaringly obvious.

Congress for the New Urbanism’s primary goals include promoting urban equity and inclusion, environmentalism, maintaining areas with varied local businesses, and tearing down highways. But city planning remains exceptionally difficult; it’s always worth hearing all possible solutions to a problem before you begin discounting them.

In conjunction with local governments or advocacy groups, CNU has identified 10 freeways it argues should be dismantled:

Claiborne Expressway (I-10), New Orleans, Louisiana

While the report goes into detail about the pitfalls of each road, most suffer similar problems. They are old, need quite a bit of costly maintenance, and are believed to have had a generally negative impact on local communities. Congress for the New Urbanism claims that their removal will be a step toward restoring the “wholeness and opportunity to the neighborhoods and business districts these routes disrupted.”

Several of the plans involve demolishing specific sections of highways, leaving the rest intact. In the case of New York’s I-81, the CNU report only recommended replacing an 1.4-mile stretch of elevated road in Syracuse (that effectively splits the city in half) with a ground-level boulevard.

From Congress for the New Urbanism:

Cities must strive to create walkable places out of former highway corridors, designed on a scale suitable for pedestrians. If the street or boulevard that replaces the highway still caters to a high volume of vehicle traffic moving at a fast pace, then many of the benefits of highway removal will fail to manifest. The boulevard will still be an effective barrier for pedestrians, businesses that are supposed to rely on foot traffic will flounder, and property values will remain stagnant. Eight uninterrupted lanes of at-grade traffic mimics the effects of a highway, including its dire public health consequences for nearby residents.

A street design that includes cars but does not make them the highest priority is key: the test of time has shown that a road of four to six lanes is adequate for auto traffic but can still be designed for people and bicycles, with well-proportioned sidewalks, frequent and well-signed crossings, street trees, and one or more medians that create a desirable and walkable avenue.

However, the report also mentions “graduated campaigns,” and your humble author noticed Detroit’s I-375 on the list. A comically short run of ugly Detroit pavement that isolated a portion of the city, it’s also a convenient stretch of road I regularly used while living in Michigan. Encouraged by Congress for the New Urbanism and local advocacy groups, The Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) has formally committed itself to I-375’s removal. And it leaves me wondering about the people utilizing the rest of the claimed “Freeways Without Futures” for their daily commute. Do you drive on or live near any of these roads?

If so, what would your life be like if it suddenly went missing?

Don’t feel bad if you have to guess; CNU is doing the same thing by assuming the removal of these highways will automatically revitalize local communities. There is no guarantee any of this will turn things around. However, the report does showcase exactly how a poorly placed road can practically obliterate neighborhoods, while highlighting that something probably needs to be done in specific instances.

If you’re interested in delving deeper into the issue, the full CNU report can be found here.

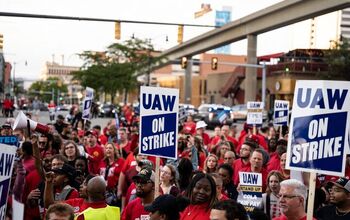

[Image: Joseph Sohm/Shutterstock]

A staunch consumer advocate tracking industry trends and regulation. Before joining TTAC, Matt spent a decade working for marketing and research firms based in NYC. Clients included several of the world’s largest automakers, global tire brands, and aftermarket part suppliers. Dissatisfied with the corporate world and resentful of having to wear suits everyday, he pivoted to writing about cars. Since then, that man has become an ardent supporter of the right-to-repair movement, been interviewed on the auto industry by national radio broadcasts, driven more rental cars than anyone ever should, participated in amateur rallying events, and received the requisite minimum training as sanctioned by the SCCA. Handy with a wrench, Matt grew up surrounded by Detroit auto workers and managed to get a pizza delivery job before he was legally eligible. He later found himself driving box trucks through Manhattan, guaranteeing future sympathy for actual truckers. He continues to conduct research pertaining to the automotive sector as an independent contractor and has since moved back to his native Michigan, closer to where the cars are born. A contrarian, Matt claims to prefer understeer — stating that front and all-wheel drive vehicles cater best to his driving style.

More by Matt Posky

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Todd In Canada Mazda has a 3 year bumper to bumper & 5 year unlimited mileage drivetrain warranty. Mazdas are a DIY dream of high school auto mechanics 101 easy to work on reliable simplicity. IMO the Mazda is way better looking.

- Tane94 Blue Mini, love Minis because it's total custom ordering and the S has the BMW turbo engine.

- AZFelix What could possibly go wrong with putting your life in the robotic hands of precision crafted and expertly programmed machinery?

- Orange260z I'm facing the "tire aging out" issue as well - the Conti ECS on my 911 have 2017 date codes but have lots (likely >70%) tread remaining. The tires have spent quite little time in the sun, as the car has become a garage queen and has likely had ~10K kms put on in the last 5 years. I did notice that they were getting harder last year, as the car pushes more in corners and the back end breaks loose under heavy acceleration. I'll have to do a careful inspection for cracks when I get the car out for the summer in the coming weeks.

- VoGhost Interesting comments. Back in reality, AV is already here, and the experience to date has been that AV is far safer than most drivers. But I guess your "news" didn't tell you that, for some reason.

Comments

Join the conversation

An article relating to this very topic was published in the April 11th 2019 edition of the National Post. I have posted a link, which may or may not 'disappear'. https://driving.ca/features/feature-story/why-more-roads-never-was-still-isnt-and-never-will-be-a-solution-to-gridlock

Having lived in the Bay area for 7-odd years, I concede I-980 is superfluous. But I-5 through Portland? The main north-south artery for the entire west coast? Are you kidding me?