Uber's Legal Woes Are Nothing Compared to Taxicabs' Early Days

The Uber transportation network has had its share of legal woes. When there’s a Wikipedia entry specifically on protests and legal action, including hundreds of lawsuits, against Uber, you know the company is doing its part in keeping attorneys employed.

Uber’s legal matters include claims of employment discrimination, harassment and retaliation, invasion of privacy, labor law violations, an intellectual property dispute with Alphabet/Google’s Waymo division over autonomous vehicles, the use of “grayballing” software to avoid detection by police enforcing local taxi laws, the possible criminal use of an application named Hell that tracked its competitors at Lyft, plus continuing drama involving Uber’s previous CEO Travis Kalanick.

That may seem like a unsavory stew of legal problems, but it’s small potatoes compared to the early days of the taxicab business, when bribery, stock manipulation, trademark infringement, jury tampering, bombings, and even murder was how business was done.

About 100 years ago, a Russian Jewish immigrant named Abe Lomberg started a company in Joliet, Illinois to build bodies for the many automobile manufacturing firms that had sprung up in Illinois, Indiana, and western Michigan. Lomberg’s primary customer ended up being the Commonwealth Motors Corp., a company with a complicated corporate and geographic history putting the firm in Joliet at the end of the nineteen-teens. With its reinforced and gusseted frame, Commonwealth had carved out a niche among the many car companies that were more assemblers than actual manufacturers.

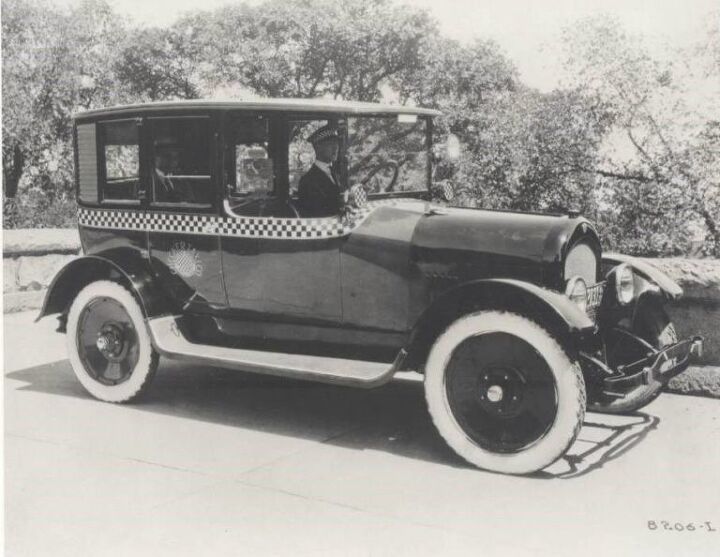

Those heavy duty frames earned Commonwealth a good reputation with Chicago taxi companies and in 1919 the company introduced the Mogul Taxi, combining its frames with a purpose-built taxicab body supplied by Lomberg Auto Body Mfg Co.

To finance the building of those bodies, Abe Lomberg borrowed funds from another Jewish immigrant from Russia, Morris Markin. Markin had the makings of a great Horatio Alger story. Born into poverty in Smolensk, he started working in a clothing factory and before he was out of his teens was in charge of the department making men’s trousers. Though Markin was personally doing well, in general Russia in the late 19th century was not a very hospitable place for Jews. For a century or so Russia experienced a cycle wherein cosmopolitan, Western-leaning reformist czars were succeeded by increasingly reactionary monarchs. When reactionaries were on the throne, Jew-haters proliferated. It was when the word “pogrom” entering the lexicon.

An uncle in Chicago invited him to emigrate to the United States and Markin landed at Ellis Island in 1913. Finding work in the clothing business, he became a skilled tailor, managing a business after his employer’s death and ultimately purchasing the firm from the his former boss’ widow. He did well enough to pay for his immediate family to come to America and started a business making off-the-rack men’s suits with one of his brothers, just before the start of World War I. That put Markin in a position to get a very profitable contract to supply the U.S. Army with uniforms.

That’s how he got the $15,000 he loaned to Abe Lomberg. When sales of the Mogul Taxi failed to meet projections, Lomberg couldn’t service his debt and Markin took over ownership of Lomborg Auto Body. There was a national economic recession in 1920-21 and Commonwealth’s production dipped to fewer than 10 taxis a week. Creditors demanded payment and the company was faced with insolvency just when the Checker Taxi Company of Chicago ordered enough vehicles to keep the company afloat, at least for a little while. However, by the end of 1921, Commonwealth Motors was bankrupt.

Markin likely foresaw the bankruptcy, as he’d already reorganized Lomberg Body in the Markin Body Corporation, somehow managing to get a concern that he’d earlier kept in business with a $15,000 loan now appraised at over $180,000 in value, probably multiples of the firm’s true value.

He offered to exchange some of his shares in Markin Body, at their inflated value, for all of the assets of Commonwealth. As there was a recession going on, the chance that Commonwealth’s receivers received better offers, or any other offers at all, is not likely, but still Markin pulled off a deal that stretched the definition of shrewd. In the spring of 1922, he merged the body and car companies into the newly organized Checker Cab Manufacturing Company. His choice of that brand name was interesting. At the time, there were Checker Cab companies operating taxis in Chicago and other big cities, but Markin’s firm had no connection to any of them, at least in its early days.

To raise operating capital, Markin floated a stock offering for 25,000 shares, but he and his company’s treasurer were convicted in 1924 of violating Illinois’ “Blue Sky” investment law by overestimating the value of assets and failing to list all debts. They were fined $2,000 and sentenced to 30 days in jail, but they appealed and the ruling was reversed.

Markin was convinced that concentrating on purpose-built taxis, and not competing for passenger car business, was the future of Checker, so he phased out the consumer automobiles in the catalog, beefed up the clutch and suspension for the remaining models and exclusively focused on taxis. The first Checker-branded taxi was the 1922 Model C. At a time before automotive styling really existed, to make his taxis stand out, Markin started painting a checkerboard beltline on them and placed checkerboard lenses on the parking lamps.

The Joliet facility had limited capacity. Looking to expand his production, Markin settled on Kalamazoo, Michigan, where there were two underutilized car factories and a surplus of skilled autoworkers looking for work after a number of local automakers went out of business during the recession. Dort Auto Body of Flint had recently reorganized and didn’t need its Kalamazoo plant, and the modern Handley-Knight Company’s factory was not running anywhere near its capacity.

Then, as now, cities and states competed to attract manufacturing companies. Meeting with city leaders in Kalamazoo, Markin made a deal where he’d buy the Dort factory and assume control of the Handley-Knight plant, while still allowing James Handley to use the facility to assemble his own products. Unfortunately for Handley, but fortuitously for Markin, Handley died within a year, leaving control of the entire factory, just three years old, in Markin’s hands.

Another local company, the Barley Motor Car Co., had developed the well-regarded Pennant taxicab, and Markin hired the two engineers responsible for that development, Leland Goodspeed and James Stout, giving Checker a solid technical foundation.

While Markin was busy building taxicabs, there was a labor dispute going on at the Checker Taxi association in Chicago, with the Teamsters, Chauffeurs and Helpers Union trying to organize drivers. In June of 1923, union organizer Frank Sexton was shot and killed, presumably at the behest of those opposed to unionization. The following day, Markin, his wife and their kids were thrown from their beds when their home was bombed.

Markin believed he was targeted because he wouldn’t “play ball” with the union and their criminal associates. The bombing and further violence associated with the taxi war confirmed Markin’s decision to move manufacturing out of the Chicago area. The first Checker cab to be made in Kalamazoo rolled off of the former Handley-Knight assembly line on July 15, 1923. Cabs would continue to be made in Kalamazoo for six decades.

That year, Markin also established a Manhattan sales office that he named the Mogul Checker Sales Co., and an improved version of the Model H was introduced. Checker started booking substantial orders from cab companies in Detroit, Chicago, and New York City.

At the time, the taxi business, particularly in Chicago, was dominated by John D. Hertz, who owned Yellow Cab and many other transportation related businesses, including the car rental firm that still carries his name. Hertz and Markin would spar in court for years but they also competed with methods less concerned with legal niceties. In 1923, Markin was arrested and charged with bribing taxicab drivers who were testifying in a lawsuit brought against him by Hertz over the use of the checkerboard graphic motif.

Also that year in Chicago, four men riding in one of Markin’s Checker taxis tried to shoot J.S. Ringer, the superintendent of the Yellow Taxi Company. Newpapers called it a taxi war.

Despite warring taxi companies and his legal difficulties, Markin continued to grow his company. In just two years, production increased from 10 cabs a week to more than 75, and employment at the two Kalamazoo factories reached 700 workers.

Hertz started to divest his transportation holdings in the mid 1920s, selling off the Yellow Cab Manufacturing Co. to General Motors, though he still maintained his interest in the Yellow Cab. The Parmelee company, Chicago’s oldest livery firm, also held shares in Yellow Cab, as did some smaller investors.

By then, Morris Markin and a business associate, Ernest Miller, had taken control of the formerly independent Checker Taxicab Company of Chicago. Also by that time, John Hertz was losing interest in having to deal with Chicago gangsters. He approached Miller about selling Yellow Cab to Markin’s group. A plan was worked out for a sequence of business deals that ended up with Markin owning both cab companies, Hertz and his associates profiting, while minority shareholders were kept out of the loop. Markin ended up owning both major taxi companies in Chicago.

Morris Markin ran Checker Motors until his death at age 76 in 1970. He introduced the twin headlight Checker A9 taxi in 1959. If you wonder how a small company could come up with something as iconic as the A9 (the retail passenger version of the A9 was branded the Marathon), Markin had hired Herbert Snow as Checker’s head designer. He formerly worked for E.L. Cord at Auburn Cord Duesenberg.

By the time of his death, Markin was a pillar of the Kalamazoo community and the unsavory history of his company was long forgotten. Markin’s son David took over operation of the company after his father’s passing and production of the Checker taxi continued until Checker Motors stopped taxi production in 1982.

Checker diversified in the 1970s so the end of taxi production, which had been fraught with labor problems, wasn’t the end of the Checker company. Checker continued to produced stamped metal parts for the domestic auto industry, primarily General Motors. A decade ago, faced with its own eventual bankruptcy, General Motors made cuts that caused Checker itself to become insolvent and in 2009 Checker went out of business, with its assets sold off.

I have a feeling, though, wheeler-dealer that Morris Markin was, if he had been still around in 2009, he would have figured out some way to keep the company going.

[Images: Wikimedia, Checker Motors, the author]

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, the original 3D car site.

More by Ronnie Schreiber

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- CEastwood I have a friend who drives an early aughts Forrester who refuses to get rid of it no matter all it's problems . I believe it's the head gasket eater edition . He takes great pains regularly putting in some additive that is supposed prevent head gasket problems only to be told by his mechanic on the latest timing belt change that the heads are staring to seep . Mechanics must love making money off those cars and their flawed engine design . Below is another satisfied customer of what has to be one of the least reliable Japanese cars .https://www.theautopian.com/i-regret-buying-a-new-subaru/

- Wjtinfwb 157k is not insignificant, even for a Honda. A lot would depend on the maintenance records and the environment the car was operated in. Up to date maintenance and updated wear items like brakes, shocks, belts, etc. done recently? Where did those 157k miles accumulate? West Texas on open, smooth roads that are relatively easy on the chassis or Michigan, with bomb crater potholes, snow and salt that take their toll on the underpinnings. That Honda 4 will run forever with decent maintenance but the underneath bits deteriorate on a Honda just like they do on a Chevy.

- Namesakeone Yes, for two reasons: The idea of a robot making decisions based on algorithms does not seem to be in anyone's best interest, and the thought of trucking companies salivating over using a computer to replace the salary of a human driver means a lot more people in the unemployment lines.

- Bd2 Powertrain reliability of Boxer engines is always questionable. I'll never understand why Subaru held onto them for so long. Smartstream is a solid engine platform as is the Veracruz 3.8L V6.

- SPPPP I suppose I am afraid of autonomous cars in a certain sense. I prefer to drive myself when I go places. If I ride as a passenger in another driver's car, I can see if that person looks alert and fit for purpose. If that person seems likely to crash, I can intervene, and attempt to bring them back to attention. If there is no human driver, there will probably be no warning signs of an impending crash.But this is less significant than the over-arching fear of humans using autonomous driving as a tool to disempower and devalue other humans. As each generation "can't be trusted" with more and more things, we seem to be turning more passive and infantile. I fear that it will weaken our society and make it more prone to exploitation from within, and/or conquest from the outside.

Comments

Join the conversation

That is a very interesting read, and a great article too! Makes me want to read on some more. It's a rather interesting comparison too! Taxicabs here in my state no longer have age limits (since 29th July 2016) after the Taxi Industry Report (done by the Taxi Services Commission) came out and recommended the scrapping of them. The former limits being: Standard taxis/Hire Cars: Melbourne, surrounding areas and Large Regional Cities: 6.5 years (with max entry age being 2.5 years) Rural and Regional Towns: 7.5 years (with no entry age restrictions) Wheelchair Taxis: Statewide: 10.5 years (with no entry age restrictions). Since the rescinding of the age restrictions, I have noticed a trend of older private cars being liveried and used as taxis. Most I've seen tend to be from 2007-10, but I saw a 2000-02 (AU) as a spare taxi (basically one to replace a broken-down taxi etc.)!

Continuation comment: Due to the lack of age limits, the taxi variety here is amazing! I've seen (to date, and also as far to my knowledge): Audi A4 (B7) Audi Q7 (4M) Chrysler 300 (LD) Citroen C5 Ford Fairlane Ghia (BF) Ford Falcon (BF (II/III), FG and FG X) Ford Territory (SY II, SZ and SZ II) Ford Mondeo (Mk. IV) Holden Caprice/Statesman (WM, WM II) Holden Commodore (VE and VF) Holden Cruze (JH) Hyundai Elantra (MD and AD) Hyundai i40 Hyundai iMax Hyundai Sonata (NF) Kia Grand Carnival (Sedona) Kia Sportage (SL) Lexus ES (XV60) Lexus GS (L10) Lexus IS (XE30) Mercedes-Benz C-Class (W204, 205) Mercedes-Benz E-Class (W212) Mercedes-Benz Sprinter (W906) Mercedes-Benz Vito (W639) Mitsubishi ASX Nissan Qashqai Nissan X-Trail Skoda Octavia Skoda Superb Toyota Aurion/Camry (XV40, 50 and 70) Toyota Corolla (E170) Toyota Kluger (Highlander) (XU40 and 50) Toyota Prius (XW20, 30 and 50) Toyota Prius c Toyota Prius v Toyota RAV4 (XA40) Volkswagen Passat (B7 and B8)