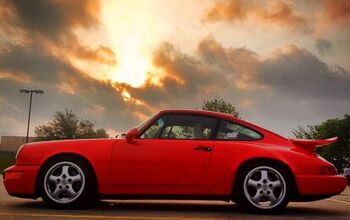

Capsule Review: (My) 1995 Porsche 911 Carrera

The magic and deadly mystery of the Porsche 911 is simply this: take a wooden baseball bat, preferably one of those thirty-five-ounce Louisville Sluggers like McGwire might have swung, hold your palm out, place the thin end of the bat there, and balance it vertically by moving your hand back and forth. See how you have to move your hand quite a bit, at unpredictable and rapid intervals, to keep the heavy end from falling? The heavy end of the bat is the 911’s engine. The thin end, where you are working, is the steering. Got it? Now run.

The Porsche “993″ was sold in Europe from 1994 to 1998. Stateside, it made the scene from 1995 to 1998. It was the last real Porsche. What’s a “real” Porsche? It’s a Carrera built without an expiration date. Air-cooled Nine Elevens are built to be operated forever. They aren’t cheap to run, and they aren’t easy to fix. But every part in the Porsche was specified with performance—not profitability—as the goal. The 993 was built using a modified form of the Toyota Production System. So it was cheaper than the truly cost-no-object 964 that preceded it. But it was still meant to last. The cars which followed are fast, delightful, wonderful. But they lack the deliberate, stubborn, bulletproof quality of a true 911.

[There is such a thing as the Hierarchy of the Porsche Nod/Wave. I am obliged to wave first to earlier 911s and 356s, with the exception of 964s, which must wave at the same time. Modern Turbo and GT3 owners must wave first, and I will perhaps wave back. 996 and 997 owners must wave first, and I will deign to nod in a superior fashion. Boxster owners receive nothing, even though I am also a Boxster owner. 944 owners receive a wave, because I am a 944 owner as well and I know how they— we—suffer. Cayenne owners can suck it.]

By modern standards, the 993 does not accelerate quickly. Though I’ve added an outrageous B&B Triflo exhaust and a hand-cut airbox, mine is barely any quicker than my Boxster S, and noticeably slower than my Audi S5. It will reach an indicated one-hundred-and-seventy miles per hour. And, yes, I demonstrated this top end to my own satisfaction right here in America, on a not-entirely-empty freeway, very possibly in the presence of women, infants, terrified puppies and combinations thereof.

At speed, the 993’s nose bobs and searches. You’re balancing the bat, understand? Porsche fitted the car with 205-section front and 255-section rear tires to make sure owners exited the road nose-first. I changed the fronts to 225-width to bring the car back to neutral balance. The cockpit is airy, thin-pillared, upright. A man could wear a hat, as Ferry Porsche did, or a helmet, as Hurley Haywood did. There is room for two adults, four in a pinch for short distances. The cliff-face, five-dial dashboard is easy to understand; only a vestigial center console really differentiates it from what was found in the 1963 original. There are three oil gauges: pressure, temperature, level. Watch them. Rebuilding the motor is a five-figure affair.

My 993 left the factory with a rather un-Porsche-like dearth of options. Seventeen-inch Cup wheels, painted in body color and since repainted under my care. Power seats. Last, not least, a mechanical limited-slip differential. On dry roads, it’s possible to exit a turn in second gear, floor the throttle, and drift the exit for hundreds of feet sideways, bouncing off the limiter. When you’re ready to straighten out, take your hands off the wheel, let it self-center, modulate the throttle, find the rear grip, shift to third, take the wheel again. Great fun. I’ve done it dozens of times.

The last time I did it, it was raining, the road had too much standing water, there wasn’t enough road friction to center the steering wheel, and when I relaxed the throttle I abruptly exited the road surface to stage right, bouncing up a curb and past a telephone pole at sixty-three miles per hour. A quick pull of the handbrake looped the car and brought me back onto the road. My passenger, facing his mortality in unexpected fashion, shuddered. I laughed. Two days later I drove down to my shop, put the 911 on the lift, took a look. No mechanical damage whatsoever. See? The last real Porsche.

More by Jack Baruth

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- ToolGuy If these guys opened a hotel outside Cincinnati I would go there to sleep, and to dream.

- ToolGuy Michelin's price increases mean that my relationship with them as a customer is not sustainable. 🙁

- Kwik_Shift_Pro4X I wonder if Fiat would pull off old world Italian charm full of well intentioned stereotypes.

- Chelsea I actually used to work for this guy

- SaulTigh Saw my first Cybertruck last weekend. Looked like a kit car...not an even panel to be seen.

Comments

Join the conversation

h82w8: Thank you for the information and advice! I will definitely look into scheduling a local test drive for a 993 or 964.

"Last, not least, a mechanical limited-slip differential. On dry roads, it’s possible to exit a turn in second gear, floor the throttle, and drift the exit for hundreds of feet sideways, bouncing off the limiter." I wonder why my 993 isn't able to do this. It has so much traction on the rear tires that I can't achieve power oversteer even on wet surfaces. I think I have no limited-slip differential. Could that be the reason?