Rare Rides Icons: Lamborghini's Front-Engine Grand Touring Coupes (Part XI)

It was a long, uphill battle to get the Espada into production. Seemingly no designer would deliver on Ferruccio Lamborghini’s desire for a four-seat grand touring coupe. While style was fine, outlandish design was unacceptable. Yet designers disappointed him on the Islero (which was supposed to be a real four-seater) and fought him on what became the Espada.

Marcelo Gandini at Bertone was forced to redesign the Espada more than once to comply with Lamborghini’s wishes, even though its Jaguar Pirana looks stayed intact. Gullwing doors were a favorite feature of Gandini’s, but Ferruccio declared they were ridiculous and impractical for such a car. And while the styling was being settled, there was quite a bit of new engineering taking place for the Espada, too.

Aside from the big-time edits to the Miura’s TP400 platform that included lengthening and reengineering to move the engine to the front, the Espada’s chassis and mechanicals underneath needed to be more practical. Remember, the original ask for the TP400 chassis spec was for a race car. Lamborghini’s three engineers worked tirelessly on the platform, only to be told Lamborghini would not, in fact, ever go racing. Remember that for later.

The length added to the chassis required the implementation of a stiffer prop shaft tunnel made of two layers. The Dallara-designed frame also required additional tubing as mounting points for the engine and suspension components. Espada had a semi-monocoque structure that was composed of pressed and folded steel, along with the company’s square section tube frame.

Espada’s suspension was fully independent with double wishbones and coil springs, as well as shock absorbers provided by Koni. There were hefty anti-roll bars at the front and rear. Wishbones were uneven in length (shorter on top) and designed to reduce camber change under hard cornering.

Enhanced chassis engineering made the platform strong enough to pass European and U.S. crash testing and meant the Espada wouldn’t feel like a V12-powered Jello on the road. Speaking of cylinders, Lamborghini’s only V12 was implemented in the Espada in the same tune as the Islero that debuted alongside it. That meant 325 horsepower at 6,500 RPM via six Weber twin carbs.

Though the power figures were quite impressive in any production car of the time, so were the large quantities of coolant and oil the engine required. The V12 needed 14 liters of coolant, and similarly, the engine held 14.3 liters of oil. Some extra luxury strain on the engine arrived via Espada’s standard air conditioning system.

Lamborghini expanded into the manufacture of air conditioning and heating systems in 1960 after Ferruccio made a visit to the United States and experienced its greatly varied climate. In conjunction with its cold Lamborghini-built AC, the Espada had a fresh air system designed specifically for its use. The system ensured fresh air reached front and rear passengers at all times.

The fresh air was accomplished via the two large ducts in the hood. They bypassed the engine entirely and were used only for occupant fresh air purposes. Another nod to rear passengers were the rear side windows, which popped outward like on any good hatchback design.

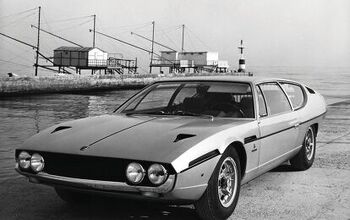

All the leather, air conditioning, and comfort for four people was capable of a top speed of over 150 miles per hour, which made it the fastest four-seat car ever made. And though its other claims to fame have since been eclipsed, the Espada is still the lowest four-seat vehicle ever produced with its overall height of just 46.7 inches.

The Espada’s wheelbase was 104.3 inches, a span of about six inches more than on the related Miura. Though it was very large (for a Lamborghini), Espada’s overall length was 186.2 inches, and it had a width of 73.2 inches. In production guise, it weighed in at 3,594 pounds, which was quite a bit heavier than the two-seat Miura’s 2,848 pounds.

Part of that weight was down to the fuel capacity required to give the GT coupe a decent range. Twin fuel tanks held a total of 25 gallons of gasoline. Both were filled via fuel doors hidden behind the grilles in the C-pillar.

Lamborghini first unveiled the Espada at the Geneva Motor Show in 1968, which was technically a prototype example but nearly production ready. Painted in metallic gold, the Espada was a stand-out of that year’s show. Between show debut and production, only a couple of the Espada’s details were altered: Some different switches were added (taken from the Miura) and a standard three-spoke steering wheel took the place of the one in the prototype.

Production began at the Sant’Agata factory almost immediately, with bodies constructed in-house by Lamborghini employees. The Series I cars were identifiable via a few key details not present on later Espadas. Most notable of these were the pointed rear lamps, which came straight from the earliest Fiat 124 coupe.

Another short-lived detail was the grille inside the lower rear window. It was a cue distilled from the hexagon rear window decoration of the Marzal show car, and not too far from the rear window slats used on the Jaguar Pirana. All of the aforementioned details were dropped at the end of Series I, so if an Espada has them it is most assuredly a very early example.

During Series I there were also mechanical improvements made on the fly. In short order Lamborghini realized the brake cooling was not sufficient, so ventilation was added to all four discs. The interior was also reworked, as the seats of the Series I were initially mounted too high.

The initial seat placement made it difficult for anyone taller than about 5’5” to fit in the front of the Espada comfortably. The answer was to lower the floor pan by 20 millimeters (.78”). The edits to trim, brakes, and headroom arrived in short order, and the Series I cars ended production in December of 1969.

At that point, Lamborghini had already sold 186 examples of the Espada, which was quickly showing to be much more popular than the more sedate Islero 2+2. Officially called the Espada 400, when it was launched in the United States it asked $21,000 ($182,392 adj.). Viewed in terms of homes, the Espada was a bit of a bargain: The average home price in 1968 was $24,700 ($214,528 adj.). Espada was also much cheaper than its closest 2+2 rival, the Ferrari Daytona (365 GTB/4) which cost $23,950 ($208,014 adj.).

Speaking of Ferrari, there was frustration within Lamborghini that Ferruccio refused to take its wares racing like its biggest competitor. And in the time between Series I and Series II, Lamborghini would lose one of its most important people. We’ll pick it up there next time.

[Images: Lamborghini, seller]

Become a TTAC insider. Get the latest news, features, TTAC takes, and everything else that gets to The Truth About Cars first by subscribing to our newsletter.

Interested in lots of cars and their various historical contexts. Started writing articles for TTAC in late 2016, when my first posts were QOTDs. From there I started a few new series like Rare Rides, Buy/Drive/Burn, Abandoned History, and most recently Rare Rides Icons. Operating from a home base in Cincinnati, Ohio, a relative auto journalist dead zone. Many of my articles are prompted by something I'll see on social media that sparks my interest and causes me to research. Finding articles and information from the early days of the internet and beyond that covers the little details lost to time: trim packages, color and wheel choices, interior fabrics. Beyond those, I'm fascinated by automotive industry experiments, both failures and successes. Lately I've taken an interest in AI, and generating "what if" type images for car models long dead. Reincarnating a modern Toyota Paseo, Lincoln Mark IX, or Isuzu Trooper through a text prompt is fun. Fun to post them on Twitter too, and watch people overreact. To that end, the social media I use most is Twitter, @CoreyLewis86. I also contribute pieces for Forbes Wheels and Forbes Home.

More by Corey Lewis

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Doug brockman There will be many many people living in apartments without dedicated charging facilities in future who will need personal vehicles to get to work and school and for whom mass transit will be an annoying inconvenience

- Jeff Self driving cars are not ready for prime time.

- Lichtronamo Watch as the non-us based automakers shift more production to Mexico in the future.

- 28-Cars-Later " Electrek recently dug around in Tesla’s online parts catalog and found that the windshield costs a whopping $1,900 to replace.To be fair, that’s around what a Mercedes S-Class or Rivian windshield costs, but the Tesla’s glass is unique because of its shape. It’s also worth noting that most insurance plans have glass replacement options that can make the repair a low- or zero-cost issue. "Now I understand why my insurance is so high despite no claims for years and about 7,500 annual miles between three cars.

- AMcA My theory is that that when the Big 3 gave away the store to the UAW in the last contract, there was a side deal in which the UAW promised to go after the non-organized transplant plants. Even the UAW understands that if the wage differential gets too high it's gonna kill the golden goose.

Comments

Join the conversation

That's a car I could marry - platonically, of course.

Can't see that the Espada chassis had much to do with the Miura. The Miura had a rear-mounted transverse V12 with the transmission and final drive all part of the engine block. So it's a bit of a stretch saying the north-south V12 and regular transmission Espada chassis was related to the Miura. It looks to be no more than an update of the 400 GT.

And short and long-arm independendent suspension was hardly unique -- a '53 Chev had that in front, it was standard for years on most cars that didn't have Mac struts. The Brits call SLA suspension double wishbone, so Honda thought that sounded more mysterious than SLA and used that terminology in ads, but it's the same thing. Only a few mid '30s cars had same length upper and lower A-arms like a '36 Chev, before the obvious advantage of a short upper arm for camber control was introduced. Of course Ford used a dead beam front axle until 1949, so it was last to climb out of the stone age.

Do you have a link to a reference that says the Miura and Espada chassis were related?