An Illustrated History Of Automotive Aerodynamics – Part 3: Finale

[Note: A significantly expanded and updated version of this article is here]

For most of the fifties, sixties and into the early seventies, automotive aerodynamicists were mostly non-existent, or hiding in their wind tunnels. The original promise and enthusiasm of aerodynamics was discarded as just another style fad, and gave way to less functional styling gimmicks tacked unto ever larger bricks. But the energy crisis of 1974 suddenly put the lost science in the spotlight again. And although historic low oil prices temporarily put them on the back burner, as boxy SUVs crashed through the air, it appears safe to say that the slippery science has finally found its place in the forefront of automotive design.

During the ornate and boxy fifties and sixties, with the exception of Citroen, Saab and a few other minor adherents, aerodynamic progress was relegated mostly to the racing world. The value of reducing forward aerodynamic drag on race cars was understood from the earliest LSR days. But what was not at all so well understood was the role of vertical aerodynamic forces, the tendency of most streamlined shapes to start acting like a wing, and want to take flight with increasing speed. This not only makes high-speed racers unstable, but also contributes to reduced cornering ability.

In 1957, British researcher G.E. Lind-Walker published the results of studies that opened the door to understanding the importance of generating downforce, particularly in racing cars. His work began a revolution in racing car design as down force played such a critical role in improving acceleration, cornering and braking, the three essential components of racing.

By the early sixties, front air dams and rear spoilers were appearing on racing cars, and no one exploited the possibilities more than Jim Hall with his highly successful Chaparral racers. The 2B above shows the first fully functional use of front and rear spoilers and fender vents, all specifically to generate down force. They made the Chaparral essentially unbeatable in 1964 and 1965.

Two years later, Hall introduced the startling Chaparral 2E, which was the paradigm-shaping race car in terms of aerodynamics. In the the 2B, the aero aids were tacked on to a relatively typical sports racer of the time; the 2E was organically designed to maximize down force, including the adjustable rear wing. The 2E profoundly influenced the whole racing world, including NASCAR. The Plymouth Superbird (and Charger Daytona) shows the extreme lengths taken by Chrysler to incorporate these on a production car for their aerodynamic benefits, although the actual racers did better when they had a much larger lip spoiler added like this one.

We’re not going to pursue the evolution of racing aerodynamics further in this limited survey, but the Chaparrals’ influence would also quickly spill over into passenger cars. GM hired an aerodynamicist back in 1953 to assist with wind tunnel tests on its turbine concept cars, although he was grossly underutilized for years. But GM’s technical assistance to the Chaparral team was a well-known fact. How much of that was aerodynamics is not clear, but the first mass production car to sport a chin spoiler like the 2B above was the 1966 Corvair. It was added in the second year of the Corvair’s 1965 re-style to reduce drag and improve down force and cross-wind stability.

In Europe, Porsche also put its racing experience to good use, and its 1972 911 Carrera RS sported a full complement of spoilers to dramatically increase high speed stability and handling.

In Europe, Citroen was mostly the keeper of the aero flame for production cars. But one outstanding example in Germany was the rotary engine-powered NSU Ro 80 from 1967.

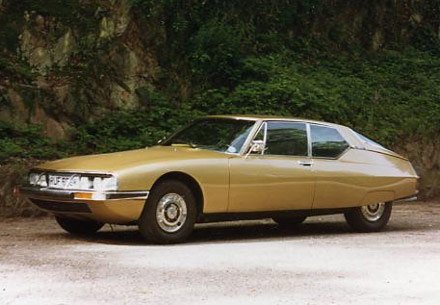

It’s Cd of .355 set a low-air mark for sedans that would stand for some years. Other than its rotary engine, the NSU was a remarkably influential car, defining the modern idiom almost perfectly. Citroen’s SM Coupe of 1970 (below) lowered the bar for coupes, with its .26 Cd, thanks in part to its adjustable suspension height setting.

After NSU was bought by VW, Audi took up the work that had begun with the Ro 80. This resulted in an aerodynamic breakthrough and one of the most influential design of the modern era, the Audi 100/5000 of 1982. With flush mounted windows and a modified wedge shape that paid tribute to the NSU, the Audi became the first mass-production sedan to achieve a Cd of .30.

In the USA, the energy crisis of 1974 suddenly thrust aerodynamics into the mainstream, and the long-neglected aerodynamicists were now finally embraced and integrated into the design process. GM’s downsized sedans of 1977 were the first to benefit from their knowledge, although its quite obvious that these cars like the Caprice below were relatively slow learners of the art. Although well behind Europe’s state of the art, even fine detailing for aerodynamic efficiency made an effective difference.

While GM was dipping their toes, Ford suddenly plunged wholly into the aerodynamic ether. Determined to jettison their boxy image after their near-death experience in 1979, Ford’s new management made a bold commitment to a complete embrace, and was determined to be the leader in the field. The 1983 Thunderbird was the first volley, but the really bold gamble was the 1986 Taurus, and its Sable sibling.

The Taurus and Sable were among the first US cars to use composite headlights, allowing for a smoother front end. The Sable was slightly more aerodynamically optimized, and beat the Audi with a .29 Cd. The race was on, and within a few years, GM would also be fielding dramatically more aerodynamic cars.

Mercedes had been utilizing aerodynamics to fine tune their cars for decades but the W126 began a more aggressive push to stay on the leading edge. The highly influential W124 (above) achieved a Cd of .28 in its most slippery variant. From this point forward, there were continual improvements from the major global manufacturers, although total aero drag often rose because cars were generally getting wider and taller too.

Needless to say, the SUV phase set aerodynamic influence in that segment back to the horse and buggy era. The ultimate wind-offender was the Hummer H2, which not only sported a .57 Cd, but its total aero drag of 26.5 sq. ft. is the highest on record for any modern vehicle listed. Wikipedia has nice charts of both Cd and total drag here.

To give GM credit, the 1989 Opel Calibra coupe set a new record for its class, with a superb Cd of .26. Fine detailing, now including the vehicle under-belly, paid off without having to resort to extreme or stylistically unpalatable measures. It led the way into the mainstreaming of super-low Cd vehicles. Incidentally, that .026 is the same value that the 2011 Chevy Volt finally attained after its extensive date with the wind tunnel.

GM’s experience with the Calibra and long hours in the wind tunnel paid off dramatically with the EV1. Electric vehicles’ limited energy storage density necessitates optimized aerodynamics if the vehicle is to run at highway speeds. Thanks to its phenomenal Cd of .195, the EV1 had a semi-respectable range of 60-100 miles, despite its old-tech lead acid batteries.

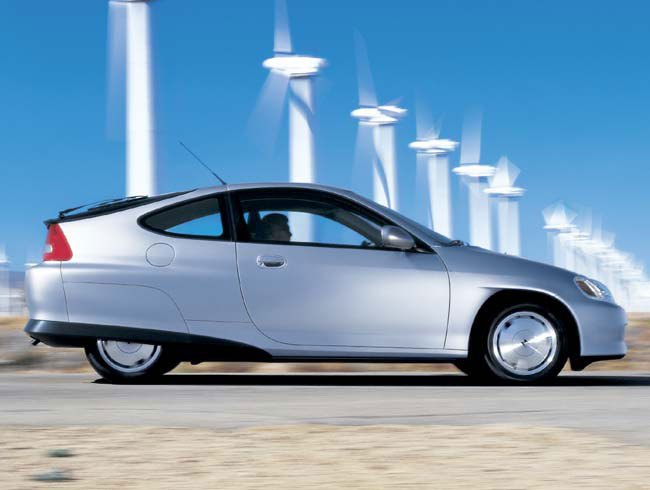

The Cd .25 barrier for mass production cars was broken by the 1999 gen 1 Honda Insight, a remarkable accomplishment considering what small car it is. Given that the Coefficient of Drag (Cd) is relative, its generally easier to attain a high number in a larger vehicle without having to resort to more drastic measures. The Insight shows plenty of those, including its rear wheel spats.

A more practical solution that also achieved a .25 Cd (in the specially optimized 3L version)was the advanced Audi A2 from 2001 (above). A lightweight four seater with aluminum construction, the TDI three-cylinder diesel powered A2 was the first four/five door car sold in Europe to be rated at less than 3 liters per 100 kilometers (78.4 US mpg). Surprisingly fun to drive too, it was not a sales success, likely due to its rather odd styling. It may well have suffered from Airflow syndrome, being just a tad too far ahead of mainstream styling acceptance.

With a Cd of .25, the 2010 Toyota Prius brings our survey of production cars to an end. It represents the current state-of-the-art for a production sedan without any compromises or additional tweaks. Undoubtedly, we’ve arrived in the full flowering of the aerodynamic age, even without the teardrop pointed tails and dorsal fins. That the aerodynamic frontier will continue to be cleft with ever less resistant vehicles is now an absolute given. We’re well beyond the point of no return, although the same sentiments were also widely held in the late thirties.

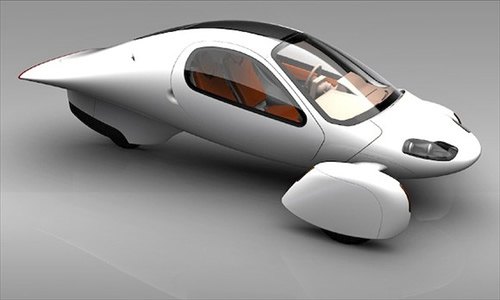

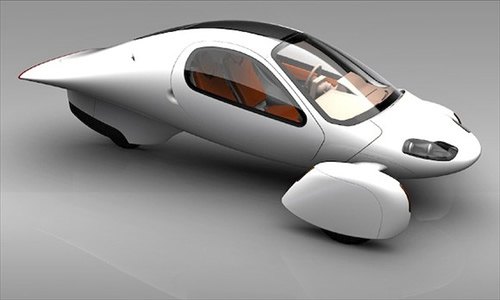

While continued refinement of the traditional automotive package will undoubtedly yield further reductions in the aerodynamic coefficient, to make a more dramatic jump requires extreme measures, like the Aptera. Its Cd of .15 is stellar, but substantial compromises are involved. It’s highly unlikely that this represents the shape of mass-production cars in the foreseeable future. But if the available energy resources for a rapidly expanding base of of global energy consumers and auto buyers happens to runs into a collision course, cars like the Aptera may well represent a possible solution to maintain personal mobility.

More by Paul Niedermeyer

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Thomas Same here....but keep in mind that EVs are already much more efficient than ICE vehicles. They need to catch up in all the other areas you mentioned.

- Analoggrotto It's great to see TTAC kicking up the best for their #1 corporate sponsor. Keep up the good work guys.

- John66ny Title about self driving cars, linked podcast about headlight restoration. Some relationship?

- Jeff JMII--If I did not get my Maverick my next choice was a Santa Cruz. They are different but then they are both compact pickups the only real compact pickups on the market. I am glad to hear that the Santa Cruz will have knobs and buttons on it for 2025 it would be good if they offered a hybrid as well. When I looked at both trucks it was less about brand loyalty and more about price, size, and features. I have owned 2 gm made trucks in the past and liked both but gm does not make a true compact truck and neither does Ram, Toyota, or Nissan. The Maverick was the only Ford product that I wanted. If I wanted a larger truck I would have kept either my 99 S-10 extended cab with a 2.2 I-4 5 speed or my 08 Isuzu I-370 4 x 4 with the 3.7 I-5, tow package, heated leather seats, and other niceties and it road like a luxury vehicle. I believe the demand is there for other manufacturers to make compact pickups. The proposed hybrid Toyota Stout would be a great truck. Subaru has experience making small trucks and they could make a very competitive compact truck and Subaru has a great all wheel drive system. Chevy has a great compact pickup offered in South America called the Montana which gm could make in North America and offered in the US and Canada. Ram has a great little compact truck offered in South America as well. Compact trucks are a great vehicle for those who want an open bed for hauling but what a smaller more affordable efficient practical vehicle.

- Groza George I don’t care about GM’s anything. They have not had anything of interest or of reasonable quality in a generation and now solely stay on business to provide UAW retirement while they slowly move production to Mexico.

Comments

Join the conversation

"Citroen’s SM Coupe of 1970 (below) lowered the bar for coupes, with its .26 Cd, thanks in part to its adjustable suspension height setting." Amazing that the Cd would be that low. The SM's aerodynamic defects range from the rain gutters, deeply recessed rear side windows, sharp edges on the roof edges and pillars. The slot between the front edge of the hood (bonnet) and the headlight glasses doesn't help, either. The USA-butchered headlight buckets, disposing of the glasses over the headlights, had to make it worse on USA models. The suspension isn't really adjustable for highway travel. There is a higher setting that raises the car about 1" above normal. The car is not drivable in the low setting, and the high setting is usable only for low speed negotiation of abrupt humps like in some driveways. The low and high positions are for tire changing. The real advantage of the Citroen suspension is that it keeps the car at the same height above the road surface despite loading and high speed lift. A fully loaded trunk (boot) and two people in the back seat do not make the rear of the car squat. The SM has a small interior for the size of the exterior. The spare tire takes up most of the otherwise decent trunk. There is no front spoiler or air dam as the shape of the rather flat bottom, lowest between the front wheels and gradually rising toward the rear, forms a venturi that creates downforce at speed. The rear edge of the rear hatch has a central spoiler to counter the lift of the sloping rear glass. The rear is a real Kammback complete with recessed rear panel to make a clean break of the airflow, minimizing drag.

Having owned a 65 Corvair without a spoiler in front, I decided to add one because I thoughtit look nice. To my surprise, it made a huge difference at highway speeds. The front didn't seem as light. More stability.