Who Will Design the Cars of the Future?

To paraphrase former editor of GOOD, Cord Jefferson, we Millennials are cold-blooded killers. Whether it’s due to lack of income or interest, few industries have been unaffected by our non-traditional spending habits. The auto industry has been especially vulnerable; I have attended academic conferences and read countless thinkpieces theorizing ways to motivate Millennials to fall in love with automobiles like their parents did. Finding buyers for all of these future cars will be tricky, but there’s a greater problem: If nobody in my generation cares for cars, who will do the work to design them?

Even more bleak are the prospects for students who are actually passionate about automobiles. One current transportation design student told me it is easier to get picked for NFL draft than it is to get a job designing cars for a major automaker. In the past, two schools dominated auto design education in America: Detroit’s College for Creative Studies and Pasadena’s ArtCenter College of Design. Today, graduates from these prestigious (and expensive) schools have to compete against a global talent pool, all vying for a limited number of internships.

With such overwhelming odds stacked against them, who would even encourage a prospective student to apply?

The Optimist

Stewart Reed is that person. Dean of ArtCenter’s Transportation Design program, Reed has crafted scissor door dune buggies with Bruce Meyers and re-skinned Peter Mullin’s 1934 Type 64 Bugatti. I encountered Reed at the college’s Pasadena campus during their annual Car Classic concours d’elegance last month. In between showing off a pair of Faraday Future concept cars designed by one of his former students (ArtCenter alumni Richard Kim), showing off his own entry, a 1972 Citroën SM to Ferrari collector David Lee (above), and announcing the winners of the concours (Bruce Meyer’s 1960 Cunningham Corvette, below, took home honors in the American division), Reed was enjoying a well-deserved Sierra Nevada. He was running on three hours sleep, but was generous with his time, discussing a range of topics from classic coachbuilding to modern production methods.

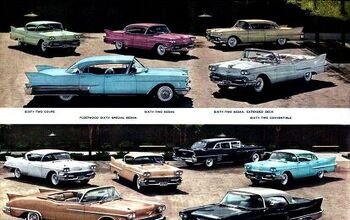

“You remember that Cunningham I made with Bob Lutz?” Reed asks, “My partner in Detroit, who did all my CAD work for that car, told me about a 3D printer that can print at 1 meter x 1 meter x 2 meters in – name your material: aluminum, stainless steel, titanium…” Reed trailed off, shaking his head, his implication obvious. If his students will no longer be limited by traditional tool-and-dye stamping, they could produce panels in any conceivable shape. The modern designs we consider extreme – the layered headlights of Aston-Martin’s One-77, the front grille of the new Lexus RX series – will be rendered ”classic” in the same way as the once-radical tail fins of a 1948 Cadillac.

The promise of truly revolutionary car design, not based on brand heritage or mechanical constraints like driveshaft tunnels or combustion engines, was too close for Reed to ignore. And the effortless reproducibility of printed parts implied something even more intriguing: A rebirth of coachbuilding. Designers of all stripes adore the pre-WWII coach-built era for elevating personalization to the level of art, with craftsmanship that (supposedly) can’t be equaled today. But the benefit of 3D printing is that limited production runs of, say, 10 cars can be executed with perfect accuracy while still offering opportunities for individual customization. Reed can see a future where automotive design can be truly localized, tailored to a single environment with local materials in the same way as clothing or food are now. No wonder Reed is so optimistic.

The Enthusiast

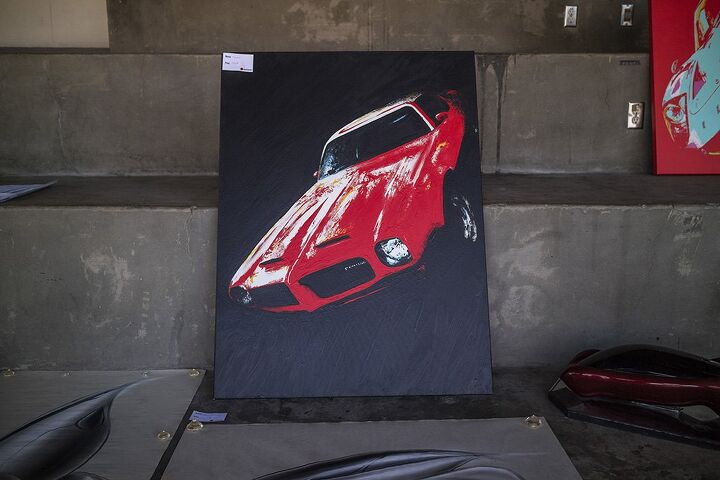

I found Matt Reginer underneath the Sinclair Pavilion outside the crowds of the CarClassic, standing behind a table with some of his vellum drawings for sale. Reginer’s entrepreneurship was admirable, but what initially attracted me to his booth was a printed sign that read: “Your contributions fund my tuition and a new pair of tires.” If that wasn’t enough to prove his enthusiast credentials, a stylized version of a Pontiac Firebird accompanied Reginer’s streamlined originals.

I asked what car he was driving: “A Pontiac G6 GTC – the coupe,” he replied. Clearly, Reginer was a Pontiac fan. After I double-checked that he wasn’t talking about owning the rabbit-toothed GXP model, I asked Reginer about his prospects — he was the design student who told me about the odds of getting a job in the industry. Reginer said that he had applications out for internships at Tesla and Ford, as well as a few others. Part of what students are buying with an ArtCenter degree is access to these companies. And though internal competition has to be extreme, winning an internship at a prestigious automaker like Porsche would increase a young designer’s chances of scoring a real job after graduation.

That’s what happened to Derek Jenkins, most recently V.P. of Design at Lucid Motors, who landed a job at Audi after graduating from ArtCenter, then jumped to Mazda. Jenkins was serving as Director at Japanese brand’s Irvine studio when the fourth generation “ND” MX-5 was designed. A similar thing happened to Franz von Holzhausen, designer of the Tesla Model S, who worked on the New Beetle after graduation (under the direction of another ArtCenter alumni, J. Mays). My favorite von Holzhausen design has to be the Saturn Sky, made alongside the Pontiac Solstice when he was serving as Design Director at General Motors. Both the Solstice and Sky are co-designs — collaborations with Holzhausen’s wife, Vicki Vlachakis (another ArtCenter alumni).

You get the picture. A pricey design school might represent a narrow path to the hallowed ground of an OEM design studio, but if it’s the only path, there really isn’t a choice. One online tuition calculator estimated the yearly tuition for attending ArtCenter would total $64,618, leaving four-year graduates with an average debt of $188,336 after the loans are paid with interest. As talented as he is, Reginer may have a bit more on his mind than new tires if he doesn’t land the right internship.

The Novice

When I first noticed Layla de Blok, I assumed she must have loved cars. Sitting on the lawn in front of a classic Facellia F-2, de Blok was intently sketching the French cabriolet. I asked her whether she was “product” or “transpo” (majoring in product or transportation design), a query I’d overheard another student ask.

“Ahhh, I’m only product,” de Blok admitted. Sketching cars was merely that week’s assignment in her product design class. Days prior, her class took a trip to the Petersen Museum, where she was captivated by a blue concept car from the 1960s — the Dodge Storm Z-250, one of my favorites from the collection. De Blok confessed that she didn’t notice cars before this exercise, and had certainly never drawn one before.

But for such an automotive novice, de Blok had already developed a type – slab-sided sports cars from the mid-to-late 1950s, with sparse detailing and subtle tailfins. For her, the curvaceous classics so loved by collectors could get too curvy and chromed-out; the purposeful designs of the post-WWII era were best, that brief period of minimalism before the tailfins peaked and automotive styling devolved into chrome and “surface entertainment.”

In any artistic movement, there is always a back-and-forth between minimalism and maximalism. Perhaps when the industry is ready to shift back to spartan designs, product specialists like de Blok will become highly valued. Certainly, when we ruminate over the supposedly imminent assault of autonomous cars, we are expecting them to arrive with an entirely new design language. De Blok suggests that, in this new world, the focus will be on what can be done inside the car instead of driving — environmental, product and even entertainment designers will have a hand in crafting this new interior world. Those designers who are not beholden to the past will have an advantage at creating the forms of the future.

And what does that future look like? The auto industry appears ready for its mid-cycle facelift without a locked design for the next model generation. Will autonomous cars inspire future collectors enough that they will be shown at concours d’elegance? Or will the amorphous shapes of autonomous vehicles make a business case for OEMs to hire enthusiasts like Matt Reginer to create special “heritage” models, designed to be driven by humans? Will humans still be allowed to drive in the future?

These questions troubled me as I walked back into ArtCenter’s main building, a dramatic bridge-like structure overlooking Pasadena. The whole of the concours stretched across the Hillside campus lawn, with a selection of American cars in white, French cars in blue, and the Italians, naturally, in red. It was such a well-curated, diverse display that the participants seemed hesitant to drive away, not wanting to spoil the view.

Every time I attend a concours, my worries about the future of the auto industry disappear. Who will design cars in the future? Who cares: Look at all the beautiful cars that already exist. One thing was certain: Reed was right, today’s design students have access to tools that would be as inconceivable to the builders of the past as their techniques and craftsmanship are to us. The more we celebrate and display the artifacts of automobile history, the more likely we are to capture the attention of those young people. And who knows, if we inspire enough of them, we might have cool cars to look at in the future.

[Images ©2017 Forest Casey/The Truth About Cars]

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- ToolGuy I am slashing my food budget by 1%.

- ToolGuy TG grows skeptical about his government protecting him from bad decisions.

- Calrson Fan Jeff - Agree with what you said. I think currently an EV pick-up could work in a commercial/fleet application. As someone on this site stated, w/current tech. battery vehicles just do not scale well. EBFlex - No one wanted to hate the Cyber Truck more than me but I can't ignore all the new technology and innovative thinking that went into it. There is a lot I like about it. GM, Ford & Ram should incorporate some it's design cues into their ICE trucks.

- Michael S6 Very confusing if the move is permanent or temporary.

- Jrhurren Worked in Detroit 18 years, live 20 minutes away. Ren Cen is a gem, but a very terrible design inside. I’m surprised GM stuck it out as long as they did there.

Comments

Join the conversation

I don't think the design schools are producing actual car designers anymore, have you looked at the crap on the roads today? I get zero sense that mass-market cars are designed by anyone with a pulse. let alone a white-hot desire to design a car that kicks the crap out of its competition from the car company across town. In fact, they all seems so bland as to have been designed during the "breakout" sessions at a car designers conference.

3 decades ago I interviewed with both Art Center & College for Creative Studies. I was fortunate to meet, 3 then current designers, two were working for the big 2, I spent the day shooting pool and drawing cars, with a retired Ford designer who taught at CCCS. I learned a lot when several of his past students stopped in with dreams of car designers, only to be designing Nike shoes, and Lear Sigler seats. They all were greatful for their experience, but still wanted that auto dream. I chose several different automotive paths that keep me happy.