No Fixed Abode: Steady Going Nowhere

This is Part Two; Part One is found here —JB

The Best & Brightest didn’t contest my point too strongly earlier this week when I suggested that the American family vehicle of choice has long possessed familiar dimensions despite sporting a diverse variety of exterior styles, from “tri-five” to high-hip CUV. Some of you thought it was a point too trite to make — what’s next, some assertion on my point that family cars always have four wheels? — but I think most Americans believe there’s a genuine difference between a Ford Fairmont wagon and a Ford Edge CUV.

If, on the other hand, there is not a genuine difference, it raises the question: What external force constrains it thus? What’s so special about those “A-body” dimensions? What makes us return again and again to the scene of crime, across generations, both human and mechanical?

Or at least that is the question I thought I should be asking, prior to truly thinking about it.

Today’s Accord and Camry are Descolada cars. They arrived from foreign shores, mated with the local population. The resulting modern cars are effectively ’78 Malibus with the engines turned sideways, made in American factories to fit American drivers and American traffic conditions. The Pilot and Highlander are simply the Vista Cruiser variants.

Just as obviously, it wasn’t the existing cars on the market that changed the Accord and Camry; it was the mindset of the buyers that mated with the new arrivals to the market. That same mindset is what made Ford’s product planners change the Bronco II into the four-door Explorer XLT and it’s how the funky and offbeat RAV4 of the Nineties lost character even as the wheelbase stretched and the family-to-powersports-products ratios in the brochures swung from zero:infinity to omnipresent:insubstantial.

No matter what the marketers and the factories put in front of the American buyer, it eventually becomes that car. The longer a new nameplate is on the market, even if it shouldn’t have anything to do with the core American vehicle, the closer it converges to that core. Look at the idiotic Nissan “Gripz” concept for an example of this. In today’s market, there is an absolute overload of SUVs and CUVs and sports cars are as rare as fresh water in Southern California. So why does one of the last options out there for an enthusiast have to become a CUV?

It’s simple: it will sell better. That’s always been the case. The less “Thunderbird-like” the original Thunderbird became, the better it sold. The more average a specialty car gets, the more of an audience it has. If you don’t believe me, look at how well the Mustang II did in its day.

So the product conforms to the desire, and the desire has always been there. So far so good. But why has the desire always been the same? Hasn’t life in America changed again and again since 1948 or thereabouts? It certainly has. So why hasn’t the desire for that core vehicle changed?

Maybe the key is in that B-body to A-body sales shift that happened in the early ’80s. Could it be that the American consumer really wants a B-body (think Expedition/Tahoe) but has to settle for the A-body? Is it that the A represents a sort of minimum to which the customer will adhere, but the B represents the preferred proportions?

Today’s families are half the size that they were in 1955. Why are the cars the same size? It’s at this point that I’d like to tell you the actual reason, the one that I found in a secret letter at the bottom of a desk drawer in the old Packard plant, but the truth is that I don’t really know why today’s Santa Fe is about the same size as a 1955 Chevrolet.

The best idea I can offer is this: The expectations of the average American grew throughout the past half-century even as the family sizes shrank and the divorces increased. The young American mother doesn’t feel any less entitled to a first-rate family vehicle just because she’s having half as many children; the young American father still wants to have the nicest car in the neighborhood even if he isn’t terribly interested in anything besides video games and his career any more.

Couple that with a relatively static motoring environment over the post-war period in terms of road width and toolbooth height and whatnot, and perhaps that’s enough to explain it. Parking spots are a certain size and garages aren’t going to get bigger in pre-existing houses. And that, coupled with a decrease in childbearing and an increase in television watching, is enough to keep the American car puffed up to a certain minimum size.

Or I could be completely wrong. It could all be a coincidence, could be due to something else entirely. I don’t know. What I want to think is that it’s more important, and more sinister, than that. That there is a machine under a mountain somewhere, broadcasting a single frequency. A frequency to which we must all tune. To do the same things, buy the same things, say the same things, believe the same things. To wake up at the same time and be cordial and be effective and be productive and be consumptive.

That the worth of our individual souls is in due proportion to how broken our antennas are; the less of the signal we get, the better we are. And though the mountain may be telling all of us to buy the same cars, design the same cars, build the same cars; some of us can’t quite hear it. Those people with the broken antennas are truly diverse in the sense that they don’t hold the same mental model as everyone else.

They buy weird little economy jobs and ridiculous sports cars and unnecessary off-roaders and they just don’t seem to feel the need to have the Universal American Car. God bless them; they are the reason the Corvette and every other four-wheeler you’ve ever loved exists. Everybody else is listening to the same frequency, the idea that morphs everything into some undifferentiated whole, a void without form, in endless pursuit of what they already have.

Or, it could just be that the Pontiac Bonneville Model G was that good.

More by Jack Baruth

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- SCE to AUX "we had an unprecedented number of visits to the online configurator"Nobody paid attention when the name was "Milano", because it was expected. Mission accomplished!

- Parkave231 Should have changed it to the Polonia!

- Analoggrotto Junior Soprano lol

- GrumpyOldMan The "Junior" name was good enough for the German DKW in 1959-1963:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DKW_Junior

- Philip I love seeing these stories regarding concepts that I have vague memories of from collector magazines, books, etc (usually by the esteemed Richard Langworth who I credit for most of my car history knowledge!!!). On a tangent here, I remember reading Lee Iacocca's autobiography in the late 1980s, and being impressed, though on a second reading, my older and self realized why Henry Ford II must have found him irritating. He took credit for and boasted about everything successful being his alone, and sidestepped anything that was unsuccessful. Although a very interesting about some of the history of the US car industry from the 1950s through the 1980s, one needs to remind oneself of the subjective recounting in this book. Iacocca mentioned Henry II's motto "Never complain; never explain" which is basically the M.O. of the Royal Family, so few heard his side of the story. I first began to question Iacocca's rationale when he calls himself "The Father of the Mustang". He even said how so many people have taken credit for the Mustang that he would hate to be seen in public with the mother. To me, much of the Mustang's success needs to be credited to the DESIGNER Joe Oros. If the car did not have that iconic appearance, it wouldn't have become an icon. Of course accounting (making it affordable), marketing (identifying and understanding the car's market) and engineering (building a car from a Falcon base to meet the cost and marketing goals) were also instrumental, as well as Iacocca's leadership....but truth be told, I don't give him much credit at all. If he did it all, it would have looked as dowdy as a 1980s K-car. He simply did not grasp car style and design like a Bill Mitchell or John Delorean at GM. Hell, in the same book he claims credit for the Brougham era four-door Thunderbird with landau bars (ugh) and putting a "Rolls-Royce grille" on the Continental Mark III. Interesting ideas, but made the cars look chintzy, old-fashioned and pretentious. Dean Martin found them cool as "Matt Helm" in the late 1960s, but he was already well into middle age by then. It's hard not to laugh at these cartoon vehicles.

Comments

Join the conversation

We may have less kids but we now have to place them in baby seats, then car seats, and then booster seats. As others have pointed out , we also have gotten heavier/larger. I suspect that it all boils down to the fact that virtually everything has a "sweet spot". Unisex one size fits all also applies to cars.

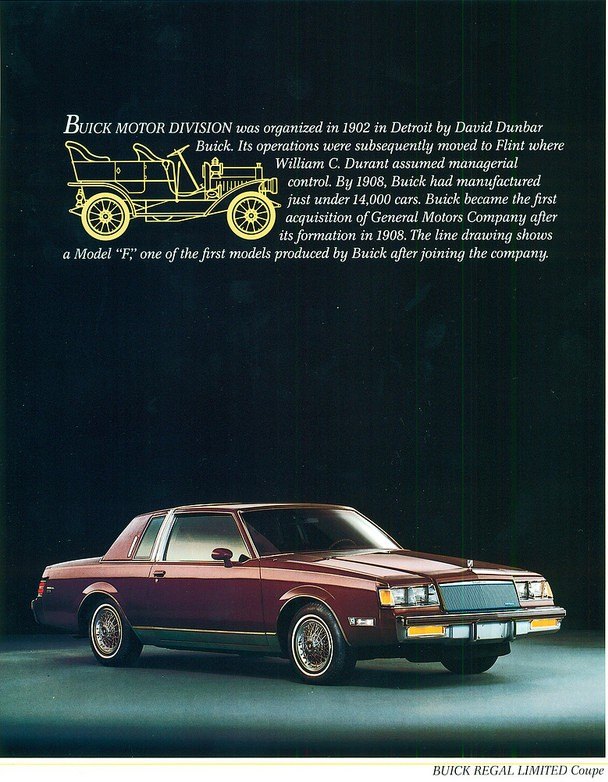

Underlying all the other issues around the size of cars we buy is the basic concept of "human factors" design: Most of us are in a certain range of physical size and reach, and that the interior of a car need only meet the sweet spot of that range for 90% of the driving experience - holding the wheel, reaching the pedals, manipulating the secondary controls. As such, the A-bodied cars met the ideal physical interior environment for most of us. When GM "down-sized" the A-body, they wrapped around this ideal interior an efficient cage and gave us the 1978 Malibus, Cutlasses, etc. We don't live on human factors alone, however. We want other kinds of cars for other reasons: Status goals, emotional reactions, where we live, expected commutes, and the other parts of our personality / life. So, we buy vehicles that vary from the A-body model and buy bigger / smaller / two-wheel / sport / truck, etc. I'll wager that interiors of American cars of the 1950's were not much different in dimension that the A-bodies of the '80s'. But, those big Buick LeSabres and Pontiac Chieftians were surrounded by huge, over-wrought cages to satisfy a temporary, post-World War II national ego-trip. When the oil embargo came along in 1973, we woke up and found those cars were 'inefficient' in their size and use of materials. Ultimately, the late 1970's A-bodies were the first to optimize the interior with the exterior. We now recognize them as pure design from an efficiency stand-point, and the all subsequent "mid-size" sedans (Accords, Camrys, etc.) are successors to those A-bodies.