Clessie Cummins Made Diesels the King of the Road … and Almost at Indy Too. Part One.

(Note to readers: This was the piece on Clessie Cummins that should have appeared first. Unfortunately, Part 2 of the series ran first and will be rerun later this afternoon — Aaron.)

Diesel engines have been in the news lately, and not for good things. The admission by Volkswagen that it has been using a software device to cheat on government emissions testing of at least some of its diesels may taint compression ignition, oil-fired engines in the passenger car market. The trucking industry, however, will continue to use diesels. That’s mostly because of a guy named Clessie Lyle Cummins.

If you’re an automobile or truck enthusiast you likely know his last name, but just as likely know nothing about him.

His accomplishments date to building a working steam engine for his family’s Indiana farm as an 11 year old in 1899, casting the engine parts from molten iron poured into hand-carved molds. As a teenager, he started to take odd jobs including fixing machinery, which led to a job at the maker of Marmon automobiles — Nordyke and Marmon. He was also member of the pit crew of Ray Harroun’s Marmon Wasp that was the winner of the very first Indianapolis 500 race in 1911, and offered suggestions that made the car faster. Cummin’s loved the Indy 500 and his engines would eventually run there, with some measure of success.

Even in the early days of motorsports, sponsors were a fact of life. Indiana banker William Irwin was one of a Harroun’s backers and so impressed by Cummins’ skills and integrity that Irwin hired him as a chauffeur and mechanic. In time the men became close friends with considerable mutual respect. Cummins admired Irwin’s business acumen and Irwin admired Cummins as a self-taught mechanical genius. That relationship would be an important factor in overcoming setbacks, leading to the eventual success of Cummins Engines.

In 1915, using Irwin’s well-equipped garage (back then you might have to make your own parts to repair an automobile), Cummins designed and built a working gasoline engine, but within two or three years his interest was drawn to a different fuel: kerosene. His first experience using the low-octane, hard-to-volatilize fuel was on a boat trip down the Mississippi River in 1912. Gasoline was still not available everywhere, while kerosene was still used for lighting in many rural areas. Clessie figured that by wrapping the outboard engine’s fuel line around the exhaust pipe before the fuel reached the carburetor, the preheated kerosene would fire and the engine ran well enough to get him home.

(Note: There is conflicting information as to the early history of the Cummins Engine company. Even the usually reliable Allpar.com is all over the place with dates and facts. The following is what seems to me to be the most likely and reliable sequence of events. If you believe any of the dates or accounts are in error, please let me know.)

It’s not known exactly when, but the first diesel engine that Clessie Cummins saw was probably in 1917 or 1918, and likely made under license from the R.M. Hvid (pronounced Veed) Company. In the early 20th century, a Dutch man named Jan Brons invented a four-cycle, compression-ignition engine and was granted a European patent in 1907. The Brons engine did not use pressurized injection, which would prove to be a technical barrier for practical diesels. Using that engine as a basis, an American named Rasmus Martin Hvid in 1915 patented an “oil injection device” and a “hydrocarbon engine governor.” The first engines built under those patents were made by the Hercules Engine Company of Evansville, Indiana and marketed by Sears-Roebuck for stationary use under the Thermoil brand.

Hvid licensed others, including Cummins, to handle any production needs that couldn’t be handled by Hercules. By then William Irwin was an official with the U.S. Department of Commerce, which may have helped in securing the license. Intellectual property in hand, with $10,000 from Irwin, Clessie Cummins incorporated the Cummins Engine Company in Columbus, Indiana in 1919.

Cummins produced its first licensed diesel engine, an 8-horsepower stationary unit, the following year. They didn’t sell many, but it brought in enough revenue to stay in business. Cummins worked on improving the performance of the Hvid engine, simultaneously working on his own original diesel designs.

It was a roller-coaster startup, with Sears initially ordering thousands of engines, only to return many of them and cancelling the remaining order. Cummins company lore puts the blame on cheap farmers, who bought the engines, used them for a season, then returned them for refunds. A more likely reason is that the Hvid Thermoil engines just didn’t work very well. That’s evidenced by other historical data and by the fact that Clessie Cummins diligently worked to improve them.

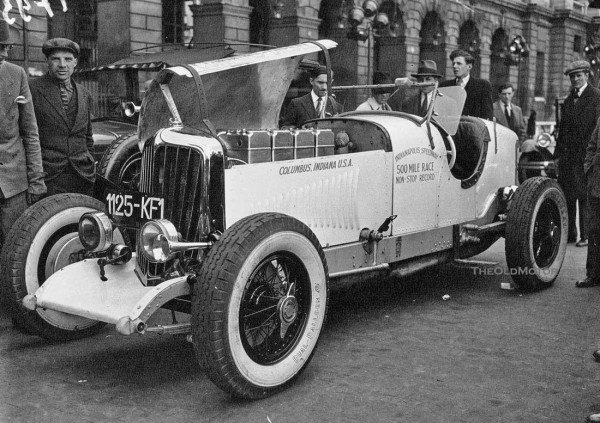

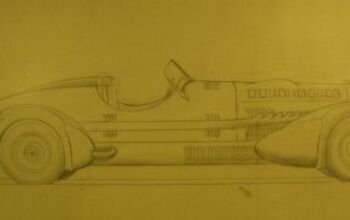

Cummins-Packard experimental record setting car.

Regardless of the actual details, the business setback didn’t thrill Irwin. Some sources say that the failed enterprise with Sears cost him $200,000, but that figure isn’t likely reliable as other sources put Irwin’s total investment in Cummins some years later at half that amount.

Clessie’s first two patents (eventually holding 33) were granted in 1921, for improved fuel delivery and manifold designs, and the first Cummins designed diesel, the Model F, was introduced in 1924.

The Cummins Model F sold, but not as well as Irwin and Cummins had hoped. Still, his backer kept faith and Cummins kept working on overcoming fuel delivery problems. For a diesel to work, a precise amount of fuel must be injected into the cylinder at a precise time. If the charge is too rich or timed poorly, it can cause a blown engine.

Cummins went through an estimated 3,000 prototypes over five years to come up with a practical mechanically controlled direct-injection system. Cummins replaced conventional needle valves with a fixed-displacement injector for each cylinder. A plunger, controlled by a geared full pump and distributor, atomized the kerosene at up to 5,000 pounds per square inch, resulting in precise fuel delivery, and even and complete burning. Cummins added high turbulence combustion chambers to better mix the injected fuel with the compressed air, resulting in better power and fuel efficiency.

As the inventor of the first practical direct-injection system — something now found on many gasoline car engines — even if you’re not a trucking enthusiast, you should tip your hat to Clessie Cummins.

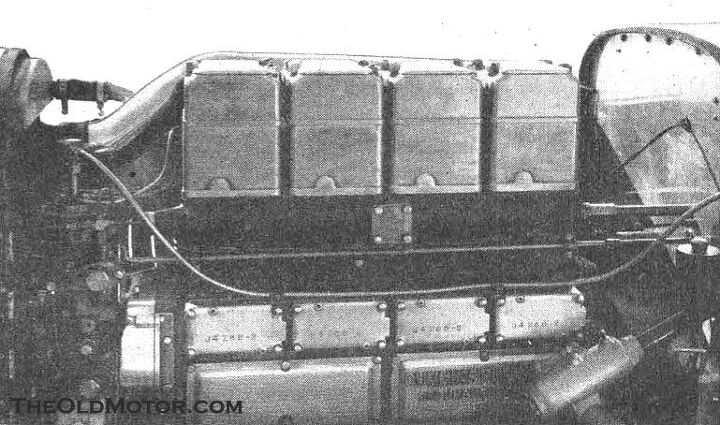

The engine that was the fruit of all that research was the revolutionary 1928 Model U. Today we’d call it a modular engine in that it was available in configurations from one to six cylinders, with an output of 10 horsepower per cylinder. It had full pressure lubrication (when many automotive engines were still using splash and drip lubrication) and it was the first production diesel in the world with fully enclosed reciprocating parts.

Cummins Model U engine

Now that he had a reliable engine, Cummins had to figure out how to sell it. Not only was he a clever engineer, he understood publicity. He convinced Irwin to buy a used 1925 Packard touring car and in the summer of 1929 installed what some sources say was a four cylinder Model U with inches to spare. Perhaps from his Indy days he knew of the need for a riding mechanic, so he chose one of his employees at the Columbus shop and headed off for the 1930 New York Auto Show, 600 miles away. The engine performed flawlessly, burning just 30 gallons of kerosene. When he arrived at the show, he found that organizers would not let him display as he had not registered in advance. As Walter Chrysler did when presented with the same situation, Clessie leased space right across the street, where the car, receipts and signed statements indicating that it had used but $1.38 worth of fuel for the trip were put on display.

Then he drove the Cummins-Packard to Daytona Beach. Kaye Don, a then-famous British racer had announced an attempt to set land speed records on the sand and Cummins knew there’d be international press there. While in Daytona, he set a world record for the flying mile in a diesel-powered vehicle at slightly over 80 mph, but the reporters were interested in how inexpensive its fuel costs were. No trailer queen, the Packard was then driven back to Indiana, consuming less than $4 worth of fuel for the entire 2,550 mile tour.

The auto show, record attempt and outstanding fuel economy garnered the publicity he wanted but Cummins Engine Company had no facilities for producing engines in large quantities. Rather than taking deposits and promising delivery dates, Cummins focused on setting up a production line.

Of course, in the intervening time between coming out with the Model U and the 1930 publicity events, there was this thing called the stock market crash of October 29, 1929, which would lead to the Great Depression. Cummins Engine was facing bankruptcy and Irwin met with Cummins to determine the company’s future. It was only their close relationship and Irwin’s confidence in Cummins that kept the company out of receivership.

The publicity earned them interest from coast-to-coast heavy truck operators, impressed by the reliability and low cost of operation, but production and sales were still just enough to keep the lights on. Clessie tried another publicity trip in the Packard, this time spending just $11.22 on fuel for the coast-to-coast trip.

While that trip generated local publicity at their stops, Cummins wanted something splashier and decided to go back to his racing roots at Indy. Indiana then was perhaps second only to Michigan when it came to building cars. In Auburn, Indiana, E.L. Cord had taken over the Auburn car company and acquired the Duesenberg brothers’ famous firm. Cummins wanted to take advantage of some loosened rules for the 500-mile race and approached Duesenberg about building him a chassis. Duesenberg was about the most successful racing chassis builder in the era and a diesel-powered “Duesey” would be sure to create publicity.

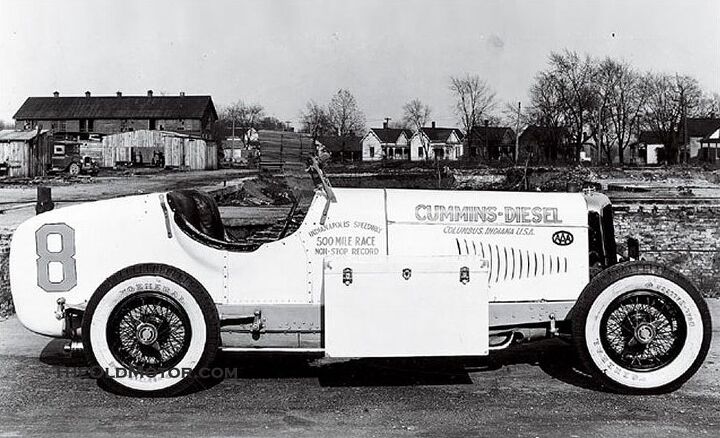

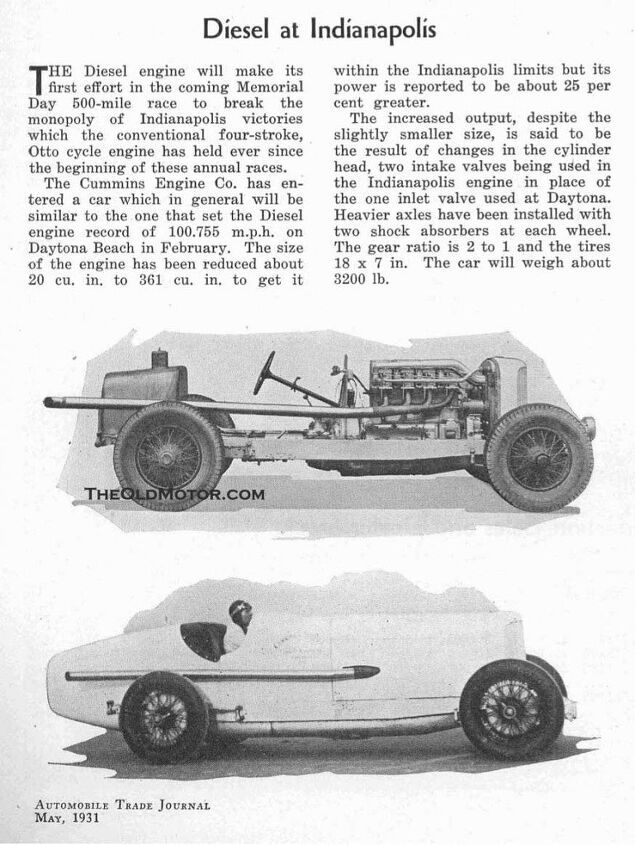

At the time, Indianapolis Motor Speedway was owned by World War I ace and businessman Eddie Rickenbacker. With the Depression, attendance was flagging and for the 1931 race the promoter thought that allowing diesels into the race might generate more interest and ticket sales. The new rules allowed Cummins to build a 366 cubic-inch version of the Model U with a 3-valve head. It was heavy, but anvil reliable and put out 85 horsepower.

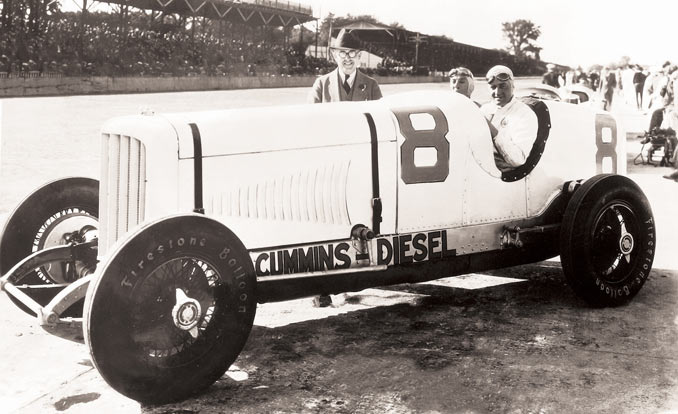

To shakedown the Cummins-Duesenberg, Clessie Cummins took another trip to Daytona, with the round trip bracketing a new diesel land speed record of over 100 mph.

Upon returning to Indiana, the streamlined sheet metal was replaced with shorter bodywork to comply with Indy’s rules. Rickenbacker allowed the car into the race under the condition that it would be disqualified if it could not keep up at 70 mph average laps. Since he knew about the land speed record attempt, that condition was moot. Testing began at the Speedway on the rebodied car, which was driven 40 miles each way from Columbus to the track for testing and even on race day.

Try to imagine an IndyCar team commuting to the race with their No. 1 car.

Dave Evans qualified the Cummins-Duesenberg at 96.871 mph, a record for diesels at Indy, but then since it was the first diesel that raced there, just about every turn of the wheels set some kind of record. At 3,386 pounds, the car was too slow to be competitive, considering the pole sitter, Billy Arnold, had run at 116 mph. Evans finished fairly well, in 13th with a decent average speed of 86.170 mph. It was the first and only time that a car has finished the Indy 500 without a stop. They knew it could complete the distance on fuel, but there were some concerns that the tires might not bear the weight of the car well. They were worn, but lasted the entire race.

Hoping to generate sales in the untapped market of Europe, Irwin and Cummins took the racer to the continent in 1932, demonstrating it in France, Italy, Switzerland and the UK. Orders were forthcoming, but again Irwin was disappointed in the results.

Still, the race and continental tour did generate interest and trucking firms started sending purchasing agents to Columbus. Despite the Depression, sales continued to rise. Clessie continued to improve his engines, applying for and receiving more patents.

Clessie must have loved the open road. As the trucking industry embraced diesels, he saw bus operators and makers as a potential market, so he put a diesel in a passenger bus and drove it cross country.

In Part Two, we’ll see Clessie Cummins persuade the trucking industry of the worthiness of the diesel and embarrass Ferrari at Indy.

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, a realistic perspective on cars & car culture and the original 3D car site. If you found this post worthwhile, you can get a parallax view at Cars In Depth. If the 3D thing freaks you out, don’t worry, all the photo and video players in use at the site have mono options. Thanks for reading – RJS

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, the original 3D car site.

More by Ronnie Schreiber

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- MaintenanceCosts The crossover is now just "the car," part 261.

- SCE to AUX I'm shocked, but the numbers tell the story.

- SCE to AUX "If those numbers don’t bother you"Not to mention the depreciation. But it's a sweet ride.

- Shipwright Great news for those down south. But will it remove internal heat to the outside / reduce solar heat during cold winter months making it harder to keep the interior warm.

- Analoggrotto Hyundai is the greatest automotive innovator of the modern era, you can take my word for it.

Comments

Join the conversation

Thank you Ronnie, I enjoyed this piece.

Outstanding, Ronnie! I cannot begin to find enough superlatives to describe what a great piece of autojournalism this is. Thank you. Looking forward to reading the second part next.