A Model Collection of Automotive History

Polymath sports marketer Fred Sharf is known in the art world for finding underappreciated genres, collecting them, researching and writing about them at an academic level, curating exhibits about them, and then donating much of what he collects to museums so others can share his eclectic interests. Among those many interests, Sharf has almost singlehandedly gotten the fine art world to start appreciating the art involved with making automobiles. Drawings and paintings long considered disposable styling studio work product by car companies are now considered collectible and worthy of art museum exhibitions.

Of course, two dimensional artwork isn’t the only thing generated by an automotive design studio. Clay and plaster models in 1:10, 1:8, 1:4, 1:2 and full scales have been part of the design process since the origins of car styling and Sharf has curated museum displays featuring those models. Harley Earl is attributed with crafting the first clay styling models, while he was still making custom cars in Los Angeles, before he was hired by General Motors. Gordon Buehrig’s invention of the “styling bridge” while he was working for E.L. Cord made it possible to take precise measurements off of those models for symmetry, scaling up designs, and creating blueprints.

Today, even though all design work is done initially in the digital domain, final judgments and business decisions are made based on physical, three dimensional models. Furthermore, even though they can now digitally CNC carve a full-scale clay model directly from the digital design files, things don’t quite look the same in real life, so designers still need the skill and art of clay modelers to fine tune their designs.

If Fred Sharf has educated the art and automotive worlds about the aesthetic value of what had formerly been thrown away (or snuck out of the studio by designers proud of their work), Sam Sandifer Jr. is specifically responsible for the increased appreciation for styling models. It’s interesting to note that as we progress into the digital age, our era will produce few physical styling studio drawings and paintings like Sharf collects, but the auto industry will always have to rely on actual physical models like Sandifer collects.

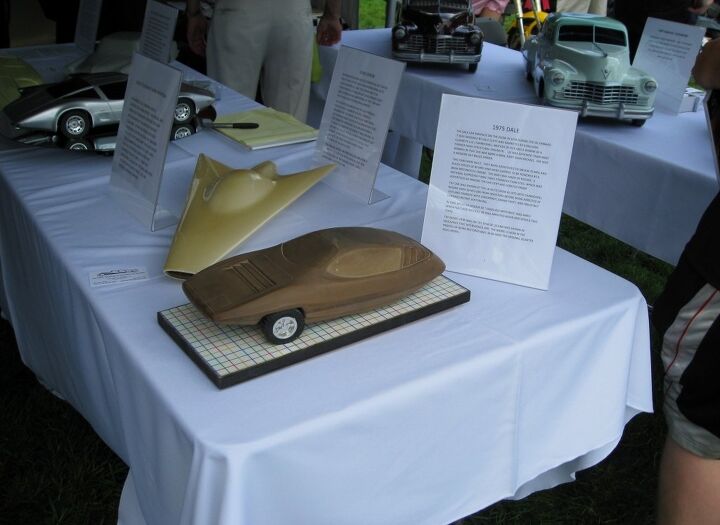

The North Carolina collector has managed to track down, save from destruction, collect and now reproduce those important artifacts of automotive history. Sandifer’s dream is to open a National Museum of Automotive Design featuring the most important pieces in his collection, but for the time being he shares them at car and toy shows.

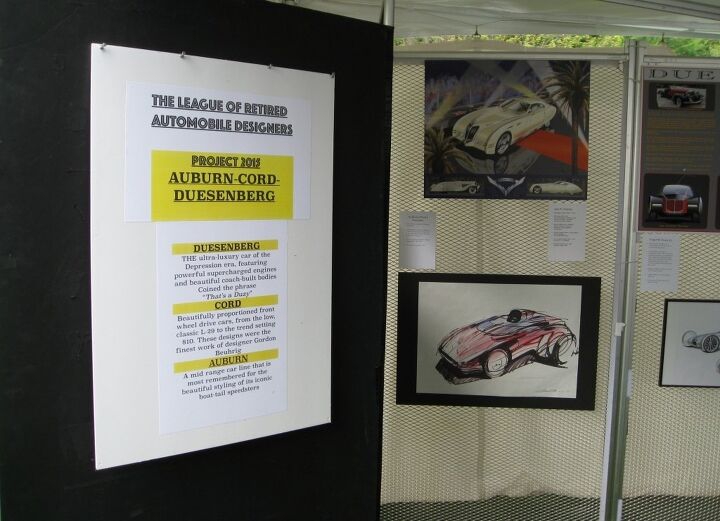

The annual Eyes on Design show held at the Edsel & Eleanor Ford estate is put on by the automotive design community in Detroit, which understands the significance and value of Sandifer’s collection and work. This year’s show had a large tent devoted to some of his more important pieces. Sandifer shared that display space with the Society of Retired Automobile Designers, one of my favorite organizations.

The three wheeler in the foreground is the model of the stillborn Dale that sat on Liz Carmichael’s desk.

Not all of Sandifer’s models were specifically styling studies. Some were also used as display pieces for executives’ desks — like the 1:10 scale 1939 Lincoln Continental that Sandifer had on display at Eyes on Design. As an artifact of automotive history, that model must surely rank very high. In the early 1940s, it sat on Edsel Ford’s desk until the scion of the Ford empire passed away from stomach cancer in 1943. It was returned to the Detroit area soon after. The Eyes on Design show at Edsel’s estate gave the model’s display special significance.

The location of a car show held by car designers at Edsel’s home is not merely coincidental. Edsel Ford had some training as a graphic artist and a collector’s eye for beautiful things. Though he probably never drew a car professionally, he can rightly be credited as one of the originators of automotive styling. It was Edsel who hired Eugene T. “Bob” Gregorie as Ford Motor Company’s first head of styling. Like Harley Earl, who couldn’t draw particularly well but could artistically wave his hand in a way that a trained stylist could understand and translate into a clay shape, Edsel had a great ability to communicate his vision to Gregorie.

The ’39 Continental started out as another one of the custom cars Edsel had Gregorie design, like his 1934 Ford Speedster.

The way the popular narrative goes, Edsel had returned from a trip to Europe and asked Gregorie to come up with a custom car for him that evoked the spirit of European sports cars, hence the name Continental. Just how continental the Continental really was, though, is not clear. Gregorie’s oral history given to the University of Michigan at Dearborn in 1985 doesn’t mention any European influence. To begin with, the Continental’s design was mocked up from an existing Lincoln Zephyr model. More to the point, automotive historian Aaron Severson’s Ate Up With Motor’s history of the Continental lays out evidence that the close-coupled, two-door hardtop or convertible coupe with long-hood/short-deck proportions, a top with blind rear quarters, and a rear-mounted external spare was a predominantly American styling idiom that went back at least to the early 1920s. Stutz even sold a model then called the Continental. It should be pointed out that two classics of postwar American automotive design, the 1956 Continental Mark II and the 1964 1/2 Ford Mustang (and subsequent Mustangs), feature long hoods and short trunk lids and many other elements with the ’39 Lincoln. Continental styling is apparently as American as apple strudel pie.

Gregorie described the genesis of the car in the 1985 oral history. Rather than summarize it, I’m just going to excerpt the original source. I can’t tell you the story better than Bob Gregorie can.

A: By the time — let’s see, it was in October/November of ’39, about four years later, that the thought came to me. We began discussing a special-built car again, and, of course, Mr. Ford’s initial thought on this special-built car was to be a Ford to glorify the Ford line. Whenever the suggestion of building that car at a Ford branch plant or interrupting Ford production in any way which it would have done, the Rouge plant fought us on it. It was just a nuisance value — anything that would interrupt production.

Q: You had a quite a bit of problem with people like…

A: Oh, [C.E.] Sorensen and Pete Martin — the production people.Q: Especially since you were working for Edsel Ford.

A: Yes. They considered it a fruitless gesture on Mr. Ford’s part. I refer to as being frivolous. I think they did too. Yeah, that’s the term they use today — frivolous. Gives the “boy” something to play with, see?

So, with Edsel Ford we might talk the thing over every few days, or every week or so, and he finally got up to the Mercury — would it be feasible to do it with the Mercury? Well, there again, we’re up against the same problem with the production plants. There’s no place in a production plant for that, without creating dissension and problems, see. No one could see a profit in it. So, at this point, an idea struck me. The old K Model Lincoln was being phased out — had been phased out, and we had one whole bay along Livernois Avenue — the Lincoln plant — where a certain amount of custom work had been done on the custom bodies that had come in the past. We had a nucleus of custom body workers at the Lincoln plant — maybe a couple hundred of them that did custom trim work, custom paint work on the custom bodies after they arrived and mounted on the old K Model chassis. So, the idea struck me. I said, “Gee, here we’ve got the Zephyr over there. We’ve got our engine components. It’s all under one roof, and we have one whole bay of this plant that’s not being used, and, at that point, without going into that phase of it with Mr. Ford — maybe I discussed it briefly, but I sketched up — I took a tenth size blueprint — a catalog sheet — what they refer to as a salesman’s handbook print, reduced down, showing the overall dimensions — head room and all that, you know. I took just a yellow pencil, a yellow crayon pencil, and I sketched in a lower hood.

Q: You’d taken a Zephyr?A: Just to sample it — Zephyr sedan, see and moved the windshield back, lowered the steering column. Like you do if you were trying to draw a fancy version of a sporty car — what you do to change it. Well, the things that came to mind at that point were that the chassis didn’t need lowering. You see, the Zephyr was designed with the concept of a chair high seat.

Q: Which at one point they had.

A: They had a chair-high seat — about an 18 inch seat in the thing, and the floor pan was very low — very shallow — the car didn’t have much of a side rail because of unit construction. It had a very shallow, maybe 3 inch side rail, something like that. It was silly, you know. I thought, well, we’ve already got a car that’s down fairly low — the foundation of it, the floor pan, see? So, I drew this thing up and sketched in the roof line, and the trunk on the back and whatnot. That afternoon Edsel Ford came by on his usual visit, and I said, “How do you like this?” He said, “Oh boy, that looks great, looks good.” So, I said, “How about making a little model? We’ll make a little tenth-size model, 17/18 inches long.” So, I had Gene Adams, a trade school boy there, I said, “Let’s make a profile template of this for modeling,” see? So, I had him glue it on a piece of masonite, you know, pressed wood, 1/8″ masonite- glued it on there with some rubber cement, and then he punched the profile and put it in a jigsaw and sawed it out, see? That was the only drawing that was ever made of the car. As people think … when I tell them it was designed or sketched in 35 minutes or so, why — well, that’s God’s honest truth. The profile [was] pleasing. That’s what sold it. He said, “That’s it,” That was all that was ever made. It was a crude, little sketch. Edsel Ford loved those simple sketches.

Q: Was this ’38?

A: This was in ’39.

Q: Early ’39?

A: No, this was in probably November of ’39. Along in November, I’d say. [Mr. Gregorie amended this to 1938.]

Q: So, he liked it immediately.

A: Yes, we had this little 10th size scaling bridge, the model wheelbase was only 10 inches, and we modeled it right in my office on a table, and Gene Adams and I modeled it right up with our hands. It wasn’t a whole car design. We had the front end and fenders.

Q: From the Zephyr?

A: Of the Zephyr. That was the new ’38 front end, which was real slick. It had a slick front end, and the fenders were reasonably decent, so we just pieced the front fenders out. I think we used the standard rear fender and did the little tire on the back, you know, and made this pretty little clay model.

Q: Tell us more about the tire on the back because that has become the hallmark of the Continental.

A: Yes, well that was part of the package, I mean, it was a necessity.

Q: But, was this your idea or did Mr. Ford like the idea from a Continental he had seen earlier?

A: I can’t say. I just can’t pinpoint that. Well, anyway, it appeared on there. I don’t know whether it was his idea or mine — I just can’t say at this point. Well, anyway, it was immediately acceptable to him, and, in fact, the trunk was too small for a spare, so it was the only place available we felt that it would be acceptable. As we all know, rear mounted spares went “back to the year one.” It surely was not for a styling “twist,” though it apparently had that effect.

Q: It was a collaboration.

A: That’s right, okay. Let’s make it that way. That was part of the package. So, we did this little model up and painted it his favorite gray with white sidewalls and nice little chrome bumpers and all, you know. This all took maybe a week. He said, “Well, how long will it take you to get one ready? I’d like to see if we can have one ready for my vacation when I go to Hobe Sound, Fla.”

Q: That’s incredible.

A: That’s right. Took the offsets off with tenth size scaling bridge, turned the figures over to Martin Rigitko, and he made a paper draft — just a rough paper draft of it — full size and sent it over to the Lincoln plant and went ahead and built one just as quick as we could.

Q: This is about December?

A: By that time it would have been December. Well, anyway, by March or late February we had the car finished ready to ship down there by truck. [1939]

Q: You shipped it down by truck.

A: Yes. Have you seen pictures of the car and all?

Q: Yes. Gorgeous.

A: It was a pretty thing, but, man, it was all full of solder to smooth it up, and heavy, you know. It was beautiful to look at, but, I mean, it was strictly a hand-made mockup sort of thing. Well, Edsel Ford had the car down there for a couple weeks, and he called me on the phone one day, and he said, “Gosh, I’ve driven this car around Palm Beach ,” and he said, “I could sell a thousand of them down here right away, quick.” He said, “They couldn’t get enough of them.” So, he said, “You’d better get over to the Lincoln Plant and talk with Robbie over there [he was the Lincoln plant superintendent over there] and see what you can do to set up an arrangement for limited production.” You know, some arch presses and whatnot, so we could build a few hundred of these to start off with. So, he said, “In the meantime, you’d better start a second one going right away,” a second hand-built one to work out mechanical details like the steering column shift which was coming in for production at that time. I went over, and Robbie and I set down. We got going right away quick. I said, “The boss man said we should build a second one of these.” He said, “Oh God, not that again!” I said, “I think it’s going to jell this time. I think we have something here.” At that point I told Mr. Ford about the advantages of building it as a Lincoln. I said, “In the first place, we can get more money for this car.” This is after he decided for just a one off. This is prior to his calling me back to build more. I sent him away with that germ in his mind. I said, “Gee, we’ve got the chassis, frame, we’ve got the suspension system, we’ve got the engine, we’ve got the steering gear and all mechanical parts. We’re not interfering with any Ford production. We’ve got all components in house, right there at the Lincoln plant, and we have the people to do the nice trim work and so on.” So, it was a natural. It just fell together that way. So, of course, the rest is history.

While the model that was on Edsel Ford’s desk was made by Gene Adams, it was likely not the same one that Gregorie described in his oral history. Still, according to Sam Sandifer, it probably was used in the styling process, perhaps for the development of the convertible roof, bumpers and other trim.

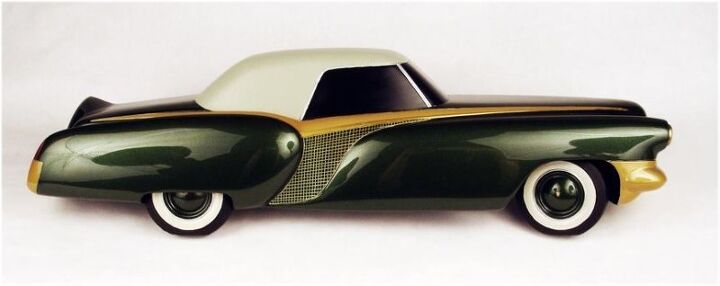

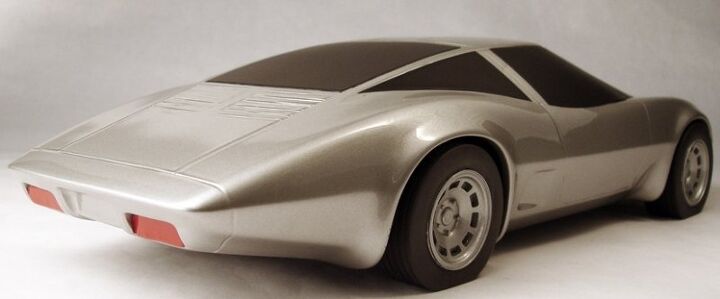

When Edsel Ford died in 1943, his office was cleaned out with most of the items put into storage, including his 1:10 scale Continental. It was discovered years later by Larry Wilson, a clay modeler who was coincidentally hired as a modeling apprentice by none other than Edsel’s father, Henry Ford. It’s still in original condition, painted the gun-metal gray that was Edsel’s favorite color for cars, though at some point it’s lost the “continental” spare tire mounted in back. Metallic grays and silvers are, to this day, considered by automotive designers to be the ideal colors to show off the shapes they design.

If Edsel Ford’s scale model of his Continental is an important piece of automotive history, Sandifer also has what could be described as a footnote to automotive history. Included in his collection is the model of the notorious Dale three wheeler that sat on the desk of fraudster Liz Carmichael, who promoted that never to be produced vehicle back in the 1970s.

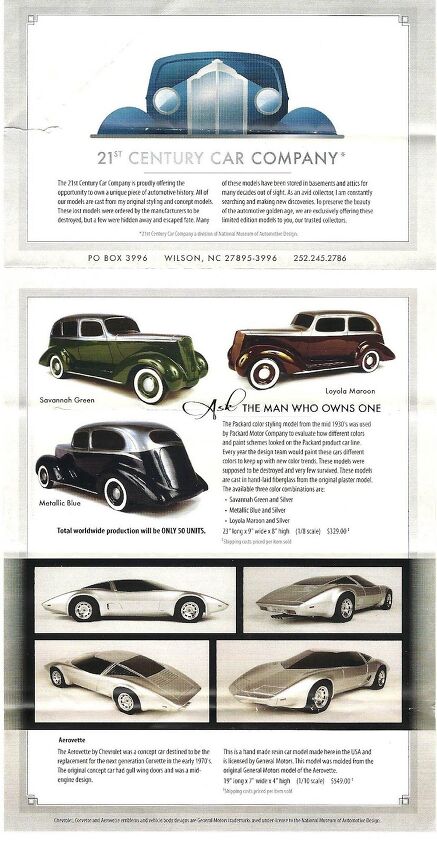

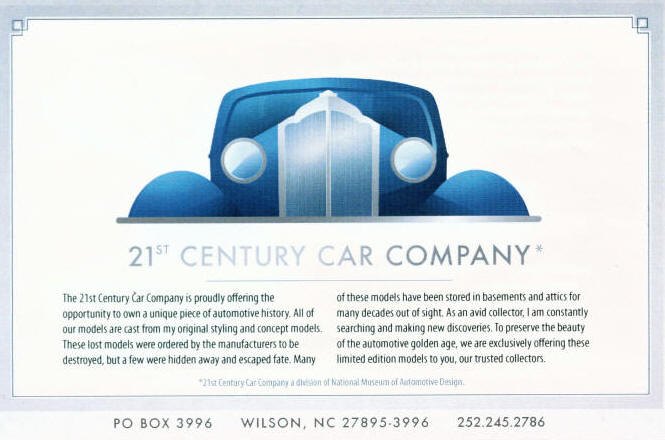

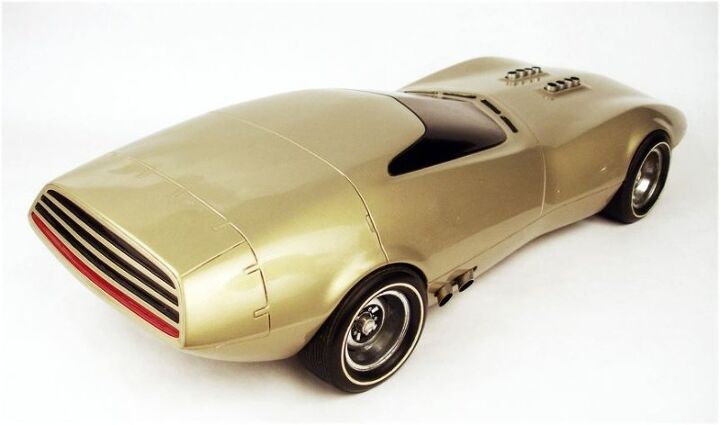

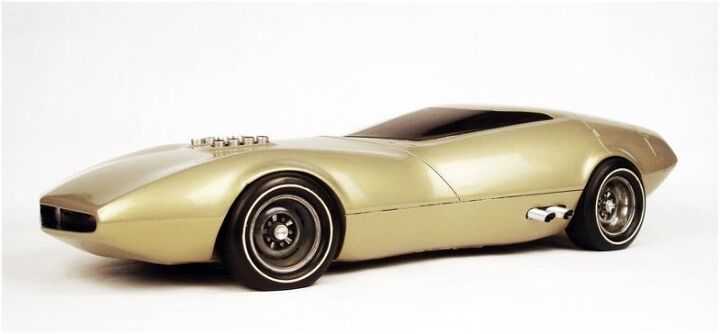

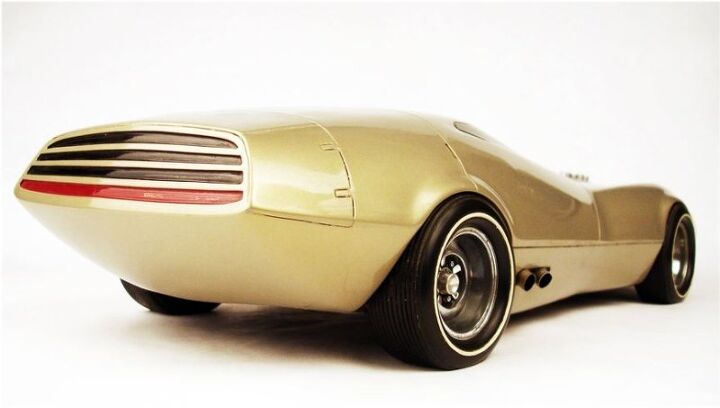

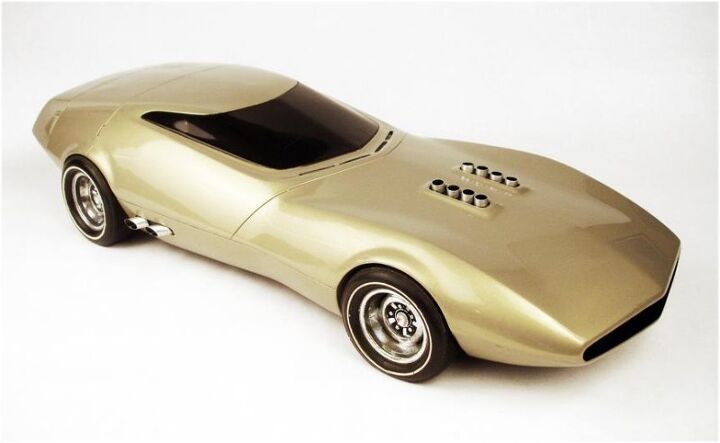

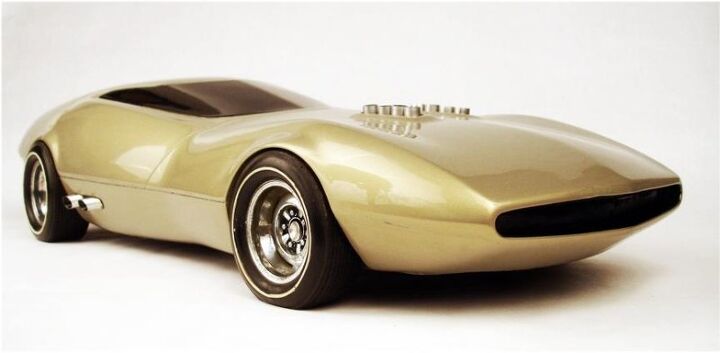

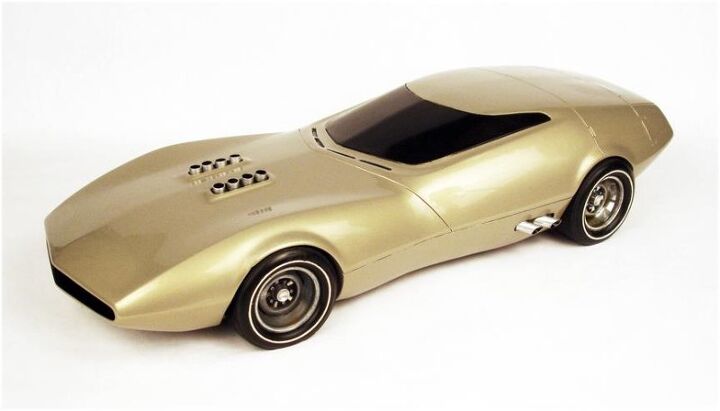

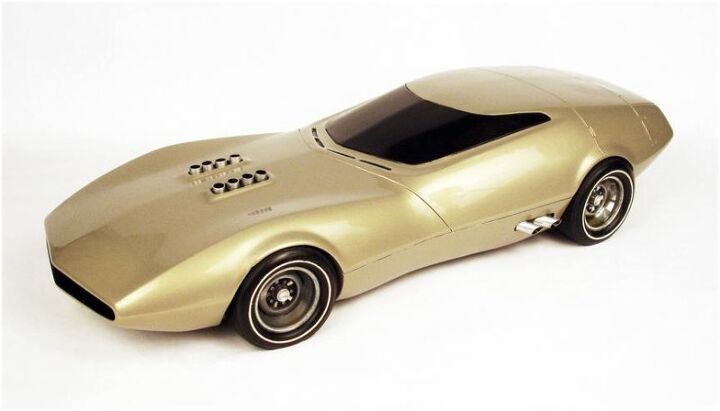

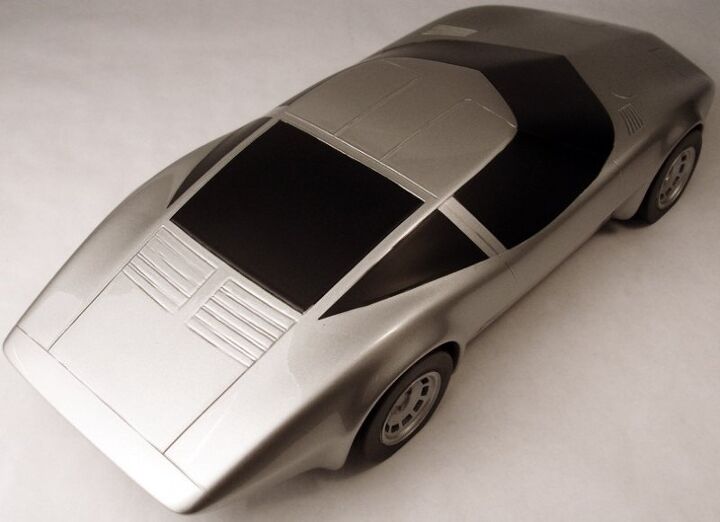

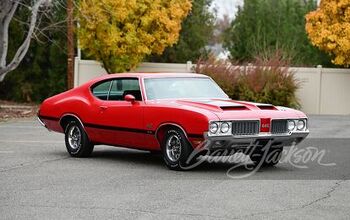

While the original styling models that Sandifer has collected are very rare, he’s made it possible for you to share his passion by making fully licensed fiberglass reproductions and selling them through the 21st Century Car Company, represented by JM Model Autos. A variety of eras are represented, including the ’39 Contintental, the 1949 Ford, the Aerovette Corvette concept and the Dodge Charger III concept. Molds have been pulled from the original clay, plaster and wood models, imperfections found in the originals have been fixed, and hand laid up fiberglass replicas are being made. Sandifer is using both old world and high-tech methods. Bumpers and other trim are made from brass, using the lost wax casting method. For some of the models, period correct wheels and tires have been modeled and replicas made with 3D printers.

They’re limited editions, so even if they are repos, they’re still collectible. At typical prices of $300 to $400 each, they’re probably more of a labor of love for Sandifer than a highly profitable business venture. You can see examples of the reproductions in the gallery below.

Photos at Eyes on Design by the author.

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, a realistic perspective on cars & car culture and the original 3D car site. If you found this post worthwhile, you can get a parallax view at Cars In Depth. If the 3D thing freaks you out, don’t worry, all the photo and video players in use at the site have mono options.

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, the original 3D car site.

More by Ronnie Schreiber

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Mebgardner I test drove a 2023 2.5 Rav4 last year. I passed on it because it was a very noisy interior, and handled poorly on uneven pavement (filled potholes), which Tucson has many. Very little acoustic padding mean you talk loudly above 55 mph. The forums were also talking about how the roof leaks from not properly sealed roof rack holes, and door windows leaking into the lower door interior. I did not stick around to find out if all that was true. No talk about engine troubles though, this is new info to me.

- Dave Holzman '08 Civic (stick) that I bought used 1/31/12 with 35k on the clock. Now at 159k.It runs as nicely as it did when I bought it. I love the feel of the car. The most expensive replacement was the AC compressor, I think, but something to do with the AC that went at 80k and cost $1300 to replace. It's had more stuff replaced than I expected, but not enough to make me want to ditch a car that I truly enjoy driving.

- ToolGuy Let's review: I am a poor unsuccessful loser. Any car company which introduced an EV which I could afford would earn my contempt. Of course I would buy it, but I wouldn't respect them. 😉

- ToolGuy Correct answer is the one that isn't a Honda.

- 1995 SC Man it isn't even the weekend yet

Comments

Join the conversation

A model of inspiration! Ronnie is a great writer to model yourself after. Sorry Ronnie. I'll show myself out. Couldn't help it. Always a great read.

The '40 Ford is one of my favorites, and the '39 and '40 Continental are very similar. Alas, the art has gone out of most contemporary automotive styling.