Honda's Not the First Car Company to Make an Airplane: The Ford TriMotor

Since this isn’t The Truth About Airplanes or even Planelopnik, we don’t generally cover aviation here at TTAC, either general or commercial (sorry about that pun). However, Honda announced that last week the first production HondaJet took its maiden test flight, near Honda Aircraft’s Greensboro, NC headquarters, and Honda does, after all, make and sell a few cars too. They aren’t the first car company, though, to get into the airplane business. As a matter of fact an earlier automaker had a seminal role in the development of commercial passenger aviation and even took a flier (sorry again, couldn’t resist) at general aviation, though that experiment was less successful. I don’t know if Soichiro Honda’s ever envisioned his motor company making jet airplanes, but since one of Soichiro’s role models, Henry Ford, helped get passenger aviation off the ground (okay, the last time, I promise) it’s not out of the realm of possibility that the thought may have crossed Mr. Honda’s mind.

You may have heard, or even seen Howard Hughes’ famous and enormous World War Two era wooden airplane nicknamed The Spruce Goose. That nickname was taken from “The Tin Goose”, the popular name for the Ford Trimotor airplane (also known as the Tri-Motor), produced by Henry Ford’s company from 1925 to 1933. It wasn’t made of tin, by the way, but rather was one of the first uses of aluminum in airplane construction. Intended for the civil aviation market, most of the 199 Trimotors that were produced carried passengers or cargo, but the plane was used all over the world for a variety of purposes, including by some countries’ militaries. One Trimotor, the one in these photographs, in the collection of the Henry Ford Museum and on display there, was used by Admiral Byrd in his expedition to fly over the South Pole.

The Ford Trimotor most likely came about because of Edsel Ford’s interest in aviation. When Edsel was just 15 years old, a year after the Model T went into production in 1908 he persuaded his father to loan him three Ford workers to help him and a friend build an experimental monoplane powered by a Model T engine. Henry had encouraged Edsel’s mechanical interests, even building him a full machine shop above the carriage house at the family’s mansion in Detroit’s Boston-Edison district. It should be noted the the Fords built that 10,000 square foot house before the Model T was ever made. The success of the Model N and Model S Fords had already made Henry Ford a wealthy man before the T became a phenomenon that changed the world. Henry alternately doted on his only son and, worried that he would grow to be the soft, effete son of a rich man, humiliated him in front of others to ‘toughen him up’. He gave Edsel great power at the family company, but limited autonomy. The senior Ford, whom I believe was not a particularly good business manager and who was an even worse manager of people, relied heavily in terms of operational management of Ford Motor Company on James Couzens and his son Edsel. Both men chafed at their overbearing employer. Couzens, though, had a choice in the matter.

James Couzens was one of Henry Ford’s earliest employees. He also invested $10,000 in the new Ford Motor Company. Few of Henry’s business associates stayed with him for their entire careers and it was after Couzens and his wife had returned to Detroit from a trip to New York City that Ford’s longtime business manager finally had enough of Henry’s ways. Couzens and his wife had spent a night out on the town in Manhattan, taking in a play and eventually getting a room at a swanky hotel. However, when Couzens got back to Dearborn he was called onto the carpet by Ford, accused of stepping out on his wife. Henry, who had a long and quite possible fecund relationshp with a young Ford employee named Evangeline Dahlinger, had another standard for his employees, and it seems that one of Harry Bennett’s spies didn’t recognize Mrs. Couzens. Irate, and by then a very wealthy man in his own right from dividends on the Ford stock he owned, Couzens quit. Later, after stockholder lawsuits over unpaid dividends and a threat by Henry to start a new car company to compete with Ford Motor Co., Ford paid Couzens something like $29 million dollars in 1919 for that initial investment of $10,000.

Edsel Ford ended up far wealthier than James Couzens but he paid a high price for that wealth and unlike Couzens there was no way that he could leave the family company. Despite their sometimes strained relationship, based upon his behavior one would have to say that Edsel loved his father. Loving a difficult parent can create stress, not to mention the stress from running a large company. The younger Ford developed stomach ulcers. His immediate family is said to have blamed Henry for Edsel’s poor health. In 1942, when undergoing surgery to repair an ulcer, doctors discovered that Edsel had rapidly metastasizing stomach cancer. He also apparently contracted undulant fever from drinking unpasteurized milk produced at the Ford Farms in Greenfield Village. Edsel Ford died in 1943 at age 49.

Two decades earlier, Edsel was one of the early investors in the Stout Metal Airplane Company. In the early 1920s, most airplanes were still relatively small aircraft built with coated fabric laid over wooden or metal frameworks. William Bushnell Stout was an aeronautical engineer who had embraced many of the principles of Hugo Junkers, the German aircraft pioneer. He had had some limited success building airplanes for the American military starting during World War One. He was an early advocate of building aircraft using duraluminum, a copper and magnesium alloy of aluminum that was age-hardenable. Stout was also a pretty savvy salesman. He sent out mimeographed letters to 100 leading business men, asking them each to invest $1,000 in his new venture. In his letter, he breezily said, “For your one thousand dollars you will get one definite promise: You will never get your money back.” It must have worked because Edsel invested and convinced his father to go in on the Stout company as well. It’s not clear how much money Stout raised. One source says $20,000, while another say it was a bit more substantial, $128,000.

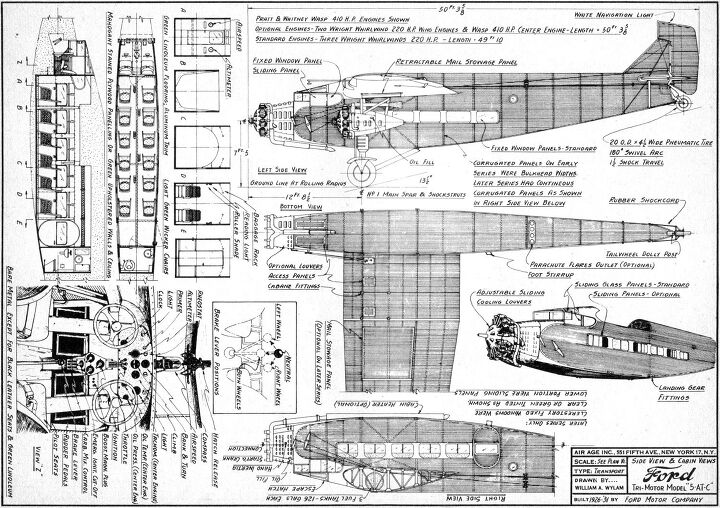

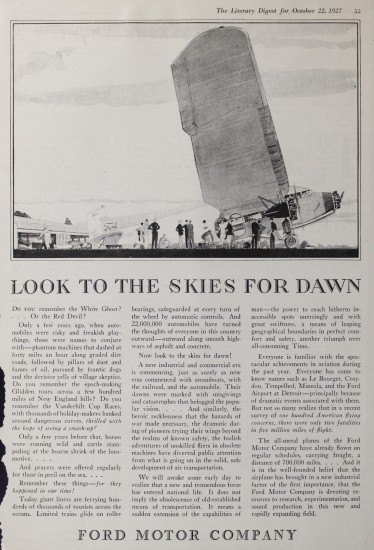

However much the initial investment was, by 1924, the Ford Airport, one of the world’s first modern airports, was operating in Dearborn, in part to serve the growing business aviation needs of FoMoCo in addition to Ford’s interest in manufacturing airplanes. Once the Trimotor was in production, Ford would take out advertisements in national magazines encouraging local municipalities to build airports as a sign of their modernity and forward thinking. In 1925 the Stout company was made a subsidiary of Ford Motor Company. Stout’s original single engine design with the wing mounted above the fuselage and made with a stressed skin of corrugated aluminum over an aluminum frame was modified to take three Curtiss-Wright radial air-cooled engines and named the Stout 3-AT. It’s possible that Stout was a better salesman than an airplane designer because while the prototype flew, it didn’t fly well. A well-timed and fortuitous fire apparently then destroyed the prototype. By then Stout had a team of engineers to work with and subsequently the far more successful 4-AT and 5-AT production models were developed. The production 4-AT Trimotor was 50 feet long with a 76 foot wingspan. It weighed just 6,500 lbs empty and had a top speed of 114 mph.

While the Trimotor was not the first all-metal airplane, it was considered to be one of the most advanced aircraft of its day. Stout used a fuselage and wing design originated by Junkers. Some of those Junkers planes were exported from Germany to the U.S. and Stout was undoubtedly also influenced by their use of corrugated aluminum as a skin. The added stiffness caused by the corrugations was considered worth the increased aerodynamic drag. That Stout borrowed Junkers designs was attested to by the fact that Junkers successfully sued Ford when the American company tried to export the Trimotor to Europe. Ford tried to countersue but a Czech court ruled that the Ford designs indeed infringed on Junkers’ patents.

The 4-AT Ford Trimotor carried a crew of three, a pilot, co-pilot and a stewardess, along with as many as nine passengers. The seats were simple and could be removed for cargo runs. The entire body of the plane, including the control surfaces was made of the ruffled aluminum. Many other aircraft continued to use fabric covered rudders, elevators and ailerons into the World War Two era. The controls surfaces were activated by cables that ran to lever arms located outside the plane near the cockpit. Interestingly, the engine instrumentation was also outside the cockpit, mounted directly on the engines but so the pilot could see them through the cockpit windshield.

A total of 86 4-AT Trimotors were produced. Specifications and performance of the slightly larger and significantly faster 5-AT Trimotor were as follows:

Crew: three (one Flight attendant)

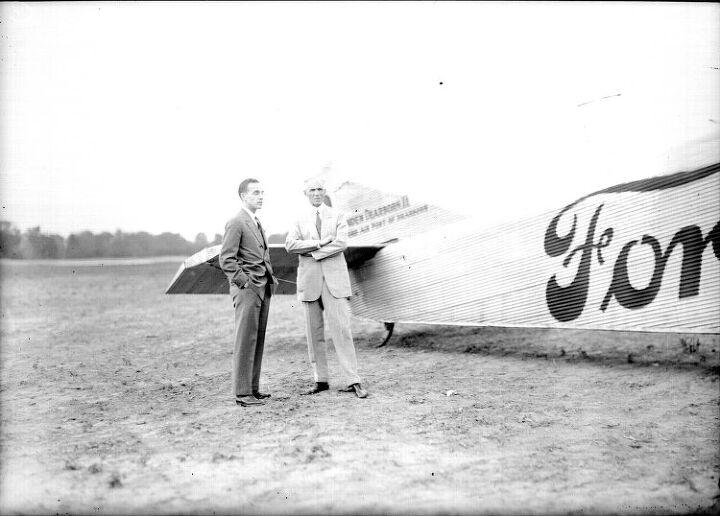

Henry and Edsel Ford and a Ford Trimotor, 1930. Photo likely taken at Ford Airport, Dearborn.

Though he likely had very little role in its design, the Ford Trimotor expressed many of Henry Ford’s core ideas that could be seen in the Model T and in the Fordson tractors. It was well-designed, reliable, and relatively inexpensive to build and to buy. In 1928, a Ford Trimotor cost $42,000, the equivalent of 84 Model A Tudors that year. The rigid metal structure and simple control systems gave the Trimotor a reputation for being able to take some abuse and like the Model T, it could be serviced and repaired almost anywhere that a pilot might land it. For bush and marine pilots, the Trimotor could have skis or pontoon floats fitted.

Though there were passenger planes before the Ford Trimotor, it made a significant impact on the then young commercial aviation industry. When introduced it was considered a major advance over other early passenger airliners. It was reliable so the planes arrived on schedule and it was comfortable enough so that when they arrived, passenger felt it was worth the fare. Well over 100 airlines around the world eventually used the Trimotor. Soon after the Trimotor’s introduction, an airline, Transcontinental Air Transport was founded specifically to used the Trimotor to provide coast-to-coast service, though passengers had to rely on rail connections for parts of the trip. A year later, Transcontinental would merge with another young airline, Western Air Service to create TWA. Pan American Airways, later PanAm, started flights from Key West to Havana, eventually adding service to Central and South America by the early 1930s. Many of the 80 small carriers that merged to form what was to become American Airlines also operated Ford Trimotors.

By the late 1920s, what by then was called the Ford Aircraft Division was considered to be the largest commercial airplane manufacturer in the world. Henry Ford even looked into producing a single seat “commuter” plane, a Model T of the air, if you will, called the Ford Flivver, a plane that would contribute to Ford withdrawing from the airplane business. I hope to cover the Flivver in a subsequent post, but for now I’ll just say that only two pilots flew the plane. Charles Lindbergh, a personal friend of Henry Ford, said it was the worst plane he ever flew. The other pilot was Henry Ford’s personal pilot, Harry Brooks, who was killed when his Flivver crashed into the ocean on a test flight, his body never recovered. Brooks death contributed to Henry Ford losing interest in aviation.

Ford published advertisements encouraging the development of modern airports.

By the early 1930s, much more modern airliners than the Trimotor were being designed and produced, starting with the Douglas DC-2. In another bit of automobile-airplane trivia, it was E.L.Cord who was one of the driving forces behind the development of the plane that took what the Ford Trimotor did for passenger aircraft and made it a far more practical way of travel, the DC-3. It’s not coincidental that in the Henry Ford Museum’s aviation section, the wings of the museum’s Ford Trimotor and Douglas DC-3 overlap each other. Those two planes pretty much created passenger air travel in the United States.

Another factor in Henry Ford leaving the aviation industry was that by 1933, the world was in the throes of the Great Depression and Ford Motor Company needed to focus on its core enterprise, building and selling cars. Speaking of which, in the early 1930s, Henry was sort of preoccupied with the development of the flathead Ford V8 engine, and meanwhile Edsel was getting on with his part of the invention of automotive styling, supervising what would become an all-time classic, the 1932 Ford. Trimotor production ended in 1933 after just fewer than 200 were built after eight years of production. It would be another eight years before Ford Motor Company would produce an airplane again, though by the time Ford Motor Company was finished with production of that particular plane, at a rate of one plane per hour, Ford could build 200 B-24 Liberators in less than two weeks at the Willow Run plant.

That’s a Douglas DC-3 in the background. Full gallery here.

As the Douglas planes supplanted the Trimotors for passenger service, the Trimotors were sold off to smaller airlines and cargo firms, some of them staying in service until the 1960s. During World War Two, Trimotors were converted for military use. Of the 199 Trimotors built, 18 of them still exist. A small number of Trimotors are even in service to this day, 80 year old airplanes that are still airworthy and providing excursion flights to vintage flight enthusiasts ( here, here and here). Stout and his team indeed built a reliable and durable aircraft.

As with many of Henry Ford’s associates, William Stout and the automaker eventually parted ways. At first Ford moved him aside from technical responsibilities, instead using the designer as a company spokesman and sending him on a publicity campaign. In 1930, Stout left the company he founded, operating the Stout Engineering Laboratory, producing a variety of aircraft as well as the Stout Scarab, an early, limited production, aerodynamic automobile powered by a rear-mounted flathead Ford V8 that is considered to have been very influential in automotive design history. Stout had many admirers in the Detroit automotive design community and while he and Henry Ford parted ways, he’s still honored. Right in the middle of Ford country in Dearborn, on Oakwood Blvd adjacent to the Ford test track and just down the street from Ford’s Product Development Center is William Stout Elementary School.

External levers controlled by the pilot actuated the plane’s control surfaces via cables. Full gallery here.

Though Ford Motor Company stopped making Trimotors in 1933 and though Henry Ford personally lost interest in aviation, commercial aviation was dramatically affected by Ford’s involvement in the Trimotor project. Many of Henry’s personal projects, like the electric car he tried to develop using his former boss and later close friend Thomas Edison’s nickel-iron batteries or Ford’s Village Industries project never made money. However, after Ford had bought out all of his partners and investors by 1919, to paraphrase Bob Dylan’s Lilly, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts, “he did whatever he wanted”. The same was true of the Ford Trimotor. Ford likely never turned a profit on the venture. However, he had a lasting impact on passenger air travel. To begin with, at the time he was America’s most celebrated industrialist. His reputation gave credibility to both the aircraft and airline businesses and through the Trimotor he helped create much of what we know today as commercial aviation: paved runways, passenger terminals, hangers, airmail and radio navigation. The Ford Trimotor also helped make “airmail” a reality.

The Ford Trimotor pictured here was the first airplane to fly over the South Pole. On November 28, 1929, Admiral Richard Byrd, along with pilot Bernt Balchen, radioman/co-pilot Harold June and photographer Ashley McKinley, flew in this Ford Trimotor from their base camp on Antartica to the South Pole and back. According to the Ford museum, Byrd’s Trimotor was “souped up”, with a 520 hp center engine flanked by two 220 hp units. The flight took them almost 19 hours and they almost didn’t make it. In order to be able to gain sufficient altitude so as not to crash into the Polar Plateau, they had to drop not only their empty auxiliary fuel tanks but also all of their emergency supplies. Had they had to emergency land the plane, they likely would have starved to death. The flight, though, was a success and Byrd’s expedition is now in the history books. In case you’re wondering why the plane has “Floyd Bennett” painted on the side, the admiral named the plane in memory of his pilot on earlier expeditions who died from pneumonia contracted while recovering from a crash.

As I said at the outset, TTAC is an automotive publication but if you’ve read this far you probably have an interest in airplanes as well. If so, the Henry Ford Museum is probably worth a visit for you (it should go without saying that the museum’s Driving America and Racing In America exhibits are a “must see” for any car enthusiast). The Ford Trimotor and Douglas DC-3 aren’t the only airplanes on display at the museum. There are two replicas of the 1903 Wright Flyer, one constructed to honor the 75th anniversary of the Kitty Hawk flight and the other built at the Wright Flyer’s centennial. In the adjacent Greenfield Village is the Wright brothers’ Dayton, Ohio bicycle shop where they honed their design using a 6 foot wind tunnel and then constructed the first Wright Flyer. Like many of the other historical buildings in the Village, the Wrights’ actual building was relocated there by Henry Ford. Other fixed-wing and rotor aircraft on permanent display in the museum include the 1909 Bleriot XI, 1931 Pitcairn Autogiro, 1939 Sikorsky VS300A Helicopter, 1920 Dayton Wright RB-1, 1927 Stinson Detroiter, 1927 Ryan “Spirit of St. Louis” Replica, 1929 Lockheed Vega, 1926 Ford Flivver, 1927 Boeing 40-B, 1915 Laird Biplane, 1917 Curtiss Biplane, and a 1926 Fokker Trimotor (used in Byrd and Bennett’s earlier attempt to fly over the North Pole).

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, a realistic perspective on cars & car culture and the original 3D car site. If you found this post worthwhile, you can get a parallax view at Cars In Depth. If the 3D thing freaks you out, don’t worry, all the photo and video players in use at the site have mono options. Thanks for reading – RJS

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, the original 3D car site.

More by Ronnie Schreiber

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Mike Bradley Driveways, parking lots, side streets, railroad beds, etc., etc., etc. And, yes, it's not just EVs. Wait until tractor-trailers, big trucks, farm equipment, go electric.

- Cprescott Remember the days when German automakers built reliable cars? Now you'd be lucky to get 40k miles out of them before the gremlins had babies.

- Cprescott Likely a cave for Witch Barra and her minions.

- Cprescott Affordable means under significantly under $30k. I doubt that will happen. And at the first uptick in sales, the dealers will tack on $5k in extra profit.

- Analoggrotto Tell us you're vying for more Hyundai corporate favoritism without telling us. That Ioniq N test drive must have really gotten your hearts.

Comments

Join the conversation

As most of the readers and commenters on TTAC, I love big things that move, and that includes aircraft and their history. The Ford Tri-Motor is on the list of my favorite aircraft. Had a nice model of one when I was young. One of these days, I'll make it to Detroit and the Henry Ford Museum. Thanks for a very well-written article, Ronnie!

I recall in my younger days building a reasonable facsimile of a Ford Trimotor out of Lego bricks, except mine was harlequin rather than gray. I did have a pilot, though, out of some Johnny Thunder set (Lego's Indiana Jones parody/ripoff in the 90's).