Car Guys & Gals You Should Know About – Roy Lunn's Resume: Ford GT40, Boss 429 Mustang, Jeep XJ Cherokee, AMC Eagle 4X4 and More!

Roy Lunn (on right) receiving an award from the Society of Automotive Engineers for the Eagle 4X4

You may not have heard the name Roy Lunn, but undoubtedly you’ve heard about the cars that he guided into being. You think that’s an exaggeration? Well, you’ve heard about the Ford GT40 haven’t you? How about the original XJ Jeep Cherokee? Lunn headed the team at Ford that developed the LeMans winning GT40. Later as head of engineering for Jeep (and ultimately VP of engineering for AMC) he was responsible for the almost unkillable Cherokee, Jeep’s first unibody vehicle, a car that remained in production for over two decades with few structural changes and could be said to be the first modern SUV. In addition to those two landmark vehicles, Lunn also was in charge of the engineering for two other influential cars, the original two-seat midengine Mustang I concept and the 4X4 AMC Eagle. If that’s not an impressive enough CV for a car guy, before Ford, he designed the Aston Martin DB2 and won an international rally. After he retired from AMC, he went to work for its subsidiary, AM General, putting the original military Humvee into production. Oh, he also had an important role in creating one of the most legendary muscle cars ever, the Boss 429 Mustang. So, yeah, you should know about Roy C. Lunn.

Aston Martin DB2. Full gallery here.

Roy C. Lunn was born in 1925 in England. I haven’t been able to find anything out about his childhood, but he must have been a bit of a prodigy. He earned mechanical and aeronautical engineering degrees and served for two years during World War II in the Royal Air Force, training as a pilot, all by the time he was a legal adult. In addition to his engineering degrees he also had training as a toolmaker and designer, and in 1946 he got his first job in the automotive industry, working for AC cars as a designer at the age of 21. His talent caught the notice of David Brown, who hired him a year later to be assistant chief designer at Aston Martin. Brown put him in charge of the DB2 program. By 1949, he was at Jowett, where he helped prepare the Jupiter sports car for production and had a hand in the development of one of the earliest fiberglass bodied cars. A competitive driver, he shared the saloon class victory co-driving a Jupiter Javelin for Marcel Becquart in the 1952 RAC International Rally of Great Britain. You can see Becquart racing that car in that rally starting at about 1:55 of this video:

After that somewhat peripatetic early career, as Lunn approached his 30s, he settled down and hired in at Ford in 1953 and was put in charge of starting up Ford of England’s new research and development center in Birmingham. His team there developed the original prototype of what would be the 105E Anglia, a critical car to the postwar success of Ford in the UK. Moving to Ford’s Dagenham works, he took on the job of product planning manager for Ford of England and ushered the Anglia into production.

105E Ford Anglia.

Emigrating to the United States in 1958, Lunn was made manager of Ford’s Advanced Vehicle Center in Dearborn. He supervised a number of projects including Ford’s first front wheel drive vehicle, the Cardinal, which was developed into the Ford of Germany’s Taunus . While the Anglia and Taunus were important cars for Ford in Europe, they’re both sedans. Lunn’s role in the development of the Mustang I concept is probably of more interest to the average car enthusiast.

P4 Ford Taunus 12M

In the early 1960s, an idea that had been percolating around Detroit since Chevy ad man Barney Clark first proposed that GM build a small, sporting four seater with classic long hood short deck proportions finally got the attention of some higher-ups at Ford. Lee Iacocca gave the go ahead to the development of a small sporty car designed to appeal to young adults. Because of Lunn’s experience in racing and as a chief designer, his team was tasked with designing a chassis and mechanical components to underpin a design based on sketches by a young Ford designer named Phil Clark (who quite likely also originated the Mustang name and galloping pony badge). Ford senior designer John Najjar, in an oral history given to the University of Michigan, Dearborn, described Lunn’s role in creating the first Mustang concept car:

Roy Lunn designed all the tubular structure, the suspension, the engines. He got all that equipment built and shipped out to [a fabricator on] the West Coast. It was all put together, we finished our clay model in something like eight weeks’ time, and, I guess, Roy had something like sixty days to build an operable vehicle. To see that thing go from an idea to finished product was an exciting time.

Ford Mustang I concept. Full galleries here and here.

You can read Lunn’s own account of the development of what is now known as the Mustang I. In January of 1963, he published a technical paper with the Society of Automotive Engineers titled, The Mustang – Ford’s Experimental Sports Car. While the four cylinder, two seat, midengine Mustang I didn’t really directly influence the production Mustang, it did end up influencing early production midengine cars like the Lotus Europa and Fiat X/19. Using the V4 engine and transaxle from the Taunus, the Mustang I concept was possibly the first midengine car to move a front wheel drive powertrain to behind the driver. Indirectly, positive consumer response to the Mustang I when it was on the show circuit convinced Ford executives to go forward with the production pony car.

By 1962 Lunn had became a U.S. citizen. Also, by then Henry Ford the second had been rebuffed in his effort to buy Ferrari. Despite the American car manufacturers’ public disavowal of racing in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Deuce wanted Ford to win, bankrolling efforts in NASCAR, and at Indianapolis with Lotus (a relationship that would also bear fruit in Formula One as the Cosworth Ford DFV engine). When Ferrari wouldn’t sell, HFII decided to beat him at his own game, at LeMans, a race important to Ferrari’s image and the racing world’s biggest stage.

The popular account of the history of Ford’s iconic 1960s racer is that to save time, Eric Broadley’s Lola Mk 6 was developed into the Ford GT40, which itself became the Mk II and Mk IV cars that won four years in a row at LeMans, 1966-69. According to the Ford engineers involved, though, while it was true that Ford used Broadley’s shop and design to jump start their endurance racing effort, the Ford GT40 was not a Lola. To manage Ford’s new GT racing effort, Lunn temporarily moved back to England, joining former Aston Martin factory racing team manager John Wyer at Broadley’s Lola, then little more than a garage. However, while Broadley’s skill at fabrication was respected, he soon was edged out and went on to develop his own very successful (and rather beautiful) competition car, the Lola T70.

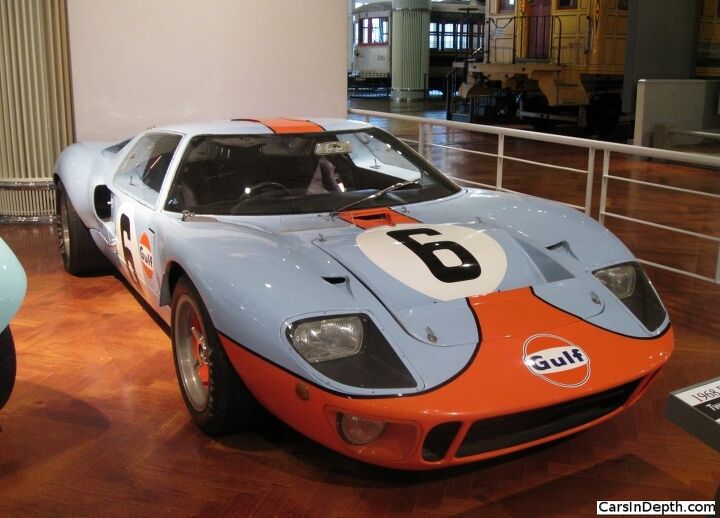

One of the original Gulf livery race cars, this GT40 Mk II won LeMans as a privateer in 1968 and 1969. Full gallery here.

In the Spring 1964 issue of Automobile Quarterly, an article based on another of Lunn’s SAE papers said, concerning Ford’s LeMans effort, “By July, 1963, a basic design and style had been established at Dearborn…”

Ford project engineer Bob Negstad, whose own resume includes designing the suspension of the Shelby Daytona Coupe, worked on the Ford GT project from the beginning and he was sent to the UK to join Lunn and Wyer at Broadley’s shop. Negstad, in an interview quoted at How Stuff Works, though, was adamant that the GT40’s design was Ford’s not Lola’s, though he acknowledged that Broadley did much of the prototype’s original build. A “brilliant fabricator”, is how Negstad described Broadley, who was trained as an architect, not an engineer.

“Broadley was technically naive,” Negstad said, “a trial-and-error man,” and the Lola shop was a “terribly old, obsolete building lit by a single 40-watt bulb.” He said that Ford was attracted to Broadley to save time. His ability to quickly build what they wanted, along with having a car of similar layout to Dearborn’s plans that could be used as test mule as they refined their own design was what put Ford and Lola together.

The Ford GT was introduced to the press and the public at the New York Auto Show in the spring of 1964. To say it had teething problems would be an understatement. Henry Ford II was increasingly embarrassed by the car’s lack of racing success, but he smartly turned the management of the factory team over to Carroll Shelby, who helped develop the GT40 into a dominant race car as well as putting together a professional racing team. Finally, in 1966, the GT40 finished 1-2-3 at LeMans. Again, Lunn published a technical paper with the SAE, in 1967, this time on the GT40’s development titled “Development of Ford GT Sports-Racing Car, Covering Engine, Body, Transaxle, Fuel System, Suspension, Steering, and Brakes.”

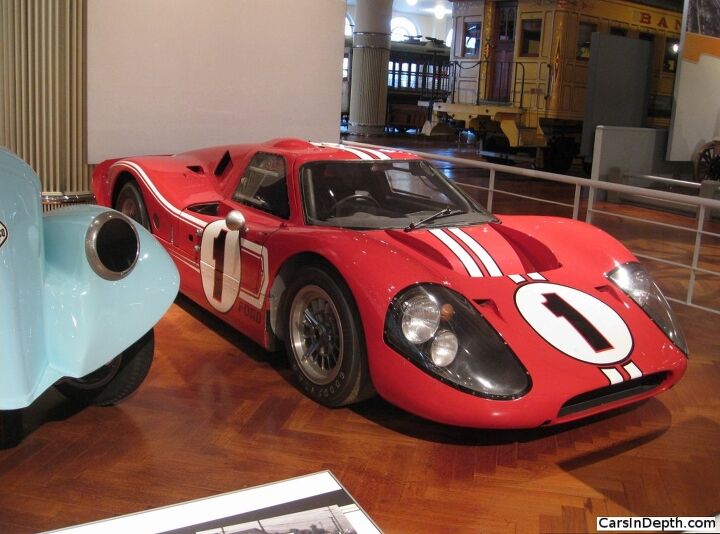

Because of the involvement of Broadley and the cars fabrication in the UK there may be some debate if the 1966 GT40 was the first “American” car with an overall win at LeMans. The next car that Ford took to LeMans, the GT40 Mark IV, was all American, designed by a team headed by Lunn in Dearborn, built at Kar Kraft in Brighton (Michigan, not England), and driven to victory by Dan Gurney and A.J. Foyt.

The 1-2-3 finish at LeMans in 1966, with that famous staged photograph showing all three cars approaching the finish line, was cause for celebration but Lunn was already focused on a new, lighter car. Two candidates were evaluated, a prototype with a tub made of aluminum sheet, designed and fabricated by McLaren Racing Ltd, and an in-house project known as the J-Car (for meeting the standards in Appendix J in the rule book), with a tub made of lightweight 1/2 thick aluminum honeycomb sandwiched between two aluminum panels, with everything bonded together. Lunn, a forward thinking engineer, liked the more modern and very stiff honeycomb material and he convinced his superiors at Ford to go in that direction.

The J-Car and GT40 Mk IV were fabricated using lightweight sandwiched aluminum honeycomb.

The first prototype, J-1, had a chassis weight of only 86 lbs, with a total vehicle weight of 2,660 lbs, coming close to meeting Lunn’s goal of a 300 lb weight reduction from the GT40 Mk II. A second prototype, J-2, was built, with Kar Kraft of Brighton, Michigan continuing with the fabrication as Ford had sold off Ford Advanced Vehicles. Unfortunately, the very talented driver, Ken Miles, was killed in a testing accident caused by mechanical failure in the J-2 car. Lunn, working with Ford chassis engineer Chuck Mountain and master fabricator Phil Remington, continued to develop the J-Car, creating a new body with a Can Am style tail, a longer nose on the front of the car and a new roofline that flowed more smoothly, allowing the use of a back window. The restyled car was renamed the GT40 Mark IV. Cars were prepared for the 1967 LeMans race, with J-5 being assigned to American drivers Gurney and Foyt. Henry Ford II was happy with the 1-2-3 finish in 1966, but he wasn’t thrilled about that car’s British origins or the fact that the drivers of the winning car, Chris Amon and Bruce McLaren, were both New Zealanders.

Note the “Gurney bubble” in the roof over the driver’s seat in the 1967 LeMans winning Ford GT40 Mk IV. Full gallery here.

J-5 needed some special bodywork that the other Mk IVs didn’t have. Dan Gurney is a rarity, a tall racer, and to give his helmet clearance, Kar Kraft had to build in a Zagato style bump in the roof, today known as the “Gurney bubble” that makes the LeMans winner immediately recognizable. Gurney celebrated by spraying the winners’ circle with champagne, initiating a racing tradition that continues to this day.

For 1968, an engine rules change meant Ford could no longer use their big 7 liter / 427 cubic inch big block. Having made his point to Enzo Ferrari and the racing world, the Deuce shuttered Ford’s endurance racing effort, selling the team to JW Engineering, where John Wyer was one of the principals. Wyer managed to convince Gull Oil’s CEO, who had some experience racing his own GT40, to sponsor the team. Gulf had recently acquired a subsidiary that fortuitously used a similar corporate color scheme to Gulf’s orange and dark blue. It was decided that the subsidiary’s powder blue and orange made a better livery for racing cars. It indeed looks great but I have to wonder that if a car wearing those colors had not won LeMans two years running, in 1968 and 1969, 45 years ago, if today we’d still consider that livery so ideal for racing cars.

Designing and building cars that won four years in a row at LeMans would make any automotive engineer’s career a successful one. Lunn’s successful management of Ford’s LeMans effort, though, was just one of his notable accomplishments.

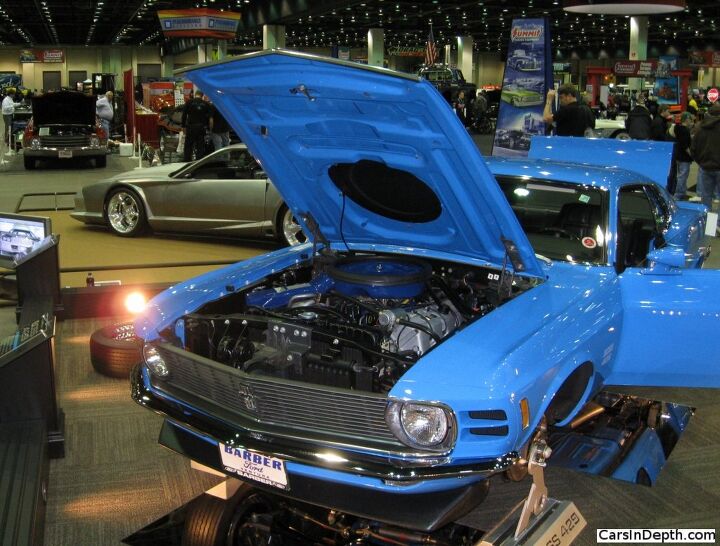

With Ford ending its factory LeMans effort, Lunn turned his attention back to production cars. As the 1960s came to a close, muscle cars were still popular and Detroit was undergoing one of its periodic horsepower wars. Having had success in Trans Am racing and in the showroom with the Boss 302 Mustang, Ford executive Bunkie Knudsen decided to up the ante and went ahead with putting Ford’s biggest performance engine, the big block based 429 cubic inch Cobra Jet V8, into the Mustang. The 429 CJ isn’t just a big block engine, it’s a physically large motor, with spark plugs inserted through the exceptionally wide valve covers. To shoehorn such a big engine in something based on the compact Falcon took some doing. The entire front end of the car had to be reengineered, with narrower shock absorber towers and a different crossmember. The work was jobbed out to Kar Kraft, but the modifications were done at Roy Lunn’s direction.

Roy Lunn was in charge of shoehorning that big and wide 429 Cobra Jet engine into the Boss 429 Mustang. Full gallery here.

The Boss 429 would almost be Ford’s last hurrah for the muscle car era. The next iteration of the Boss nameplate would be the larger and slower 1971 Boss 351 Mustang. Perhaps Lunn saw the writing on the wall for the muscle era, with emissions controls starting to be mandated, or perhaps he looked at off-road, as opposed to on-track, performance for his next challenge, or maybe he was just offered more money and a bigger title, but for whatever reason, in 1971, Lunn left Ford to become director of engineering for Jeep, which had recently been acquired by American Motors Corporation.

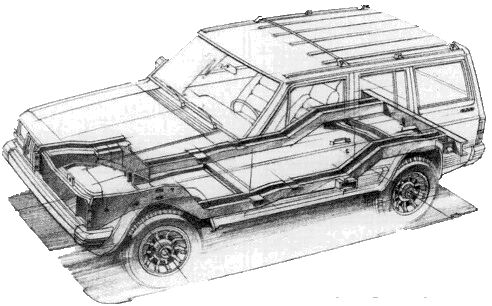

Lunn’s most notable contributions at AMC reverberate until today. He helped invent the modern SUV and if you drive something with all wheel drive that isn’t truck based, you can thank him as well. The first of those contributions was the original Jeep Cherokee, internally known as the XJ. The XJ platform was Jeep’s first attempt to build a unibody vehicle. Concerned that traditional unibody architecture would not be up to the rigors of being a trail rated Jeep, Lunn’s team came up with what AMC marketers would call the Uniframe assembly. Instead of “body on frame”, the XJ Cherokee was more like body welded to frame. The Uniframe more or less involved integrating a traditional ladder frame into a unibody top hat, welding the two into one very strong structure. Because of those beefy frame rails, to this day some people still believe that the XJ used BOF construction.

Lunn’s team designed a unibody for the XJ Cherokee so strong they were able to cut it up to make the Comanche pickup truck. Full gallery here.

Some have described the Cherokee as being overengineered, which may help explain the Jeep SUV’s legendary durability, on the road and as a production vehicle. Kiplingers listed the XJ Cherokee as one of “10 cars that refuse to die”, with many late 1980s and early 1990s models reaching 200,000 miles and more when that wasn’t commonplace, particularly with American made vehicles. Starting being built in 1984, it stayed in production in the United States into the 21st century. It lasted even longer in China. The Cherokee was the first American branded car to be made in China, the product of Beijing Jeep, also the first joint venture by an American car company in China. After AMC was acquired by Chrysler, they continued making the Cherokee in China, where it stayed in production as the Jeep 2500 until 2005.

The Cherokee’s architecture was so strong that when AMC decided to make a small truck to compete with the Ford Ranger, the Chevy S-10 and the import trucks, they were able to hack off the back half of the Cherokee’s body, add an X-shaped reinforcement between the frame rails, and bolt on a conventional separate pickup truck bed without losing structural integrity.

The XJ Cherokee didn’t just live a long production life. It’s also said by some to be responsible for the continued survival of Jeep today. The Cherokee’s sales success convinced Chrysler that AMC had viable product that didn’t overlap with vehicles in Chrysler, Plymouth and Dodge showrooms, resulting in Chrysler buying AMC to get Jeep, which continues to thrive.

Lunn’s other major contribution to the automotive world while working at AMC, the Eagle 4X4, accomplished many firsts. Today you can’t sell a luxury car north of the Mason-Dixon line if you don’t offer all wheel drive and now that Fiat Chrysler is joining Subaru with a sub $30,000 2015 Chrysler 200 AWD model, we’re likely going to see AWD proliferate in bread and butter mass market sedans. The Eagle was the first American car based vehicle with all wheel or four wheel drive. It also could be described as the first crossover, a slightly raised passenger car capable of some soft-roading.

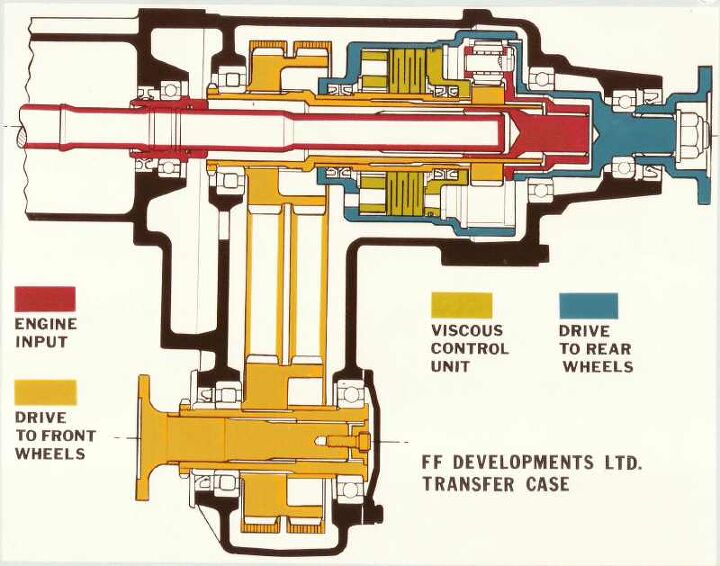

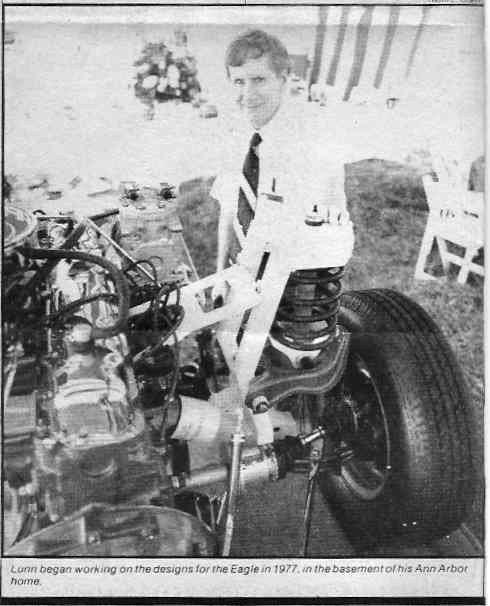

The Eagle started out as a skunk works project of Lunn and his team. The first drawings were done in the basement of Lunn’s Ann Arbor home (some very significant cars started out in designers’ and engineers’ basements and kitchens, by the way). Jeep had earlier introduced the first true production full-time four wheel drive system, offering it as an option on their utility vehicles. Based on the Ferguson Formula (FF) full-time all-wheel-drive system invented by Britain’s Ferguson Research Ltd, and developed by AMC/Jeep and the New Process Gear company, the first “QuadraTrac” system used a conventional differential between the front and rear axles. It could be engaged on the fly while driving on pavement, or just left in 4WD mode all the time.

Lunn’s team took a Concord station wagon, jacked it up a few inches, and installed one of Jeep’s Quadra-Trac systems. AMC chairman Gerald C. Meyers saw it and later recalled, “our initial reaction to Lunn’s concoction was, ‘What the hell is it?’ The body was raised an extra four inches for transfer-case clearance and the wheel wells were wide open.” The second oil crisis, in 1979, had caused Jeep sales to dip and Meyers changed his mind, seeing the concept as bridging the price gap between AMC’s economy cars and their less fuel efficient Jeeps, while giving consumers an option between the lower priced Subaru AWD vehicles and more expensive truck based four by fours from the domestic automakers. It also bridged the gap between two wheel drive cars and hardcore four wheel drive trucks. Muscular plastic fender flares bridged the large gap between the tires and the wheel wells and more body cladding visually lowered the sills.

AMC Eagle 4X4 Wagons. Full galleries here.

As mentioned, Lunn and his engineers used Jeep’s first Quadra-Trac system on their prototype, but a later transfer case from New Process replaced that conventional differential with a unit that used 42 discs spinning in a silicone based viscous fluid. That allowed differential action with less drag (and thus better fuel economy) than conventional units, making it more suitable for a passenger car. Drivetrain drag causing poorer fuel economy has always been an issue with four and all wheel drive systems. The latest AWD system that Fiat Chrysler is installing in the new Jeep Cherokee has a mode that allows the rear axle to freewheel when the trucklet is operating in 2WD. My guess is that Lunn would approve.

Lunn with the chassis and drivetrain from an AMC Eagle 4X4.

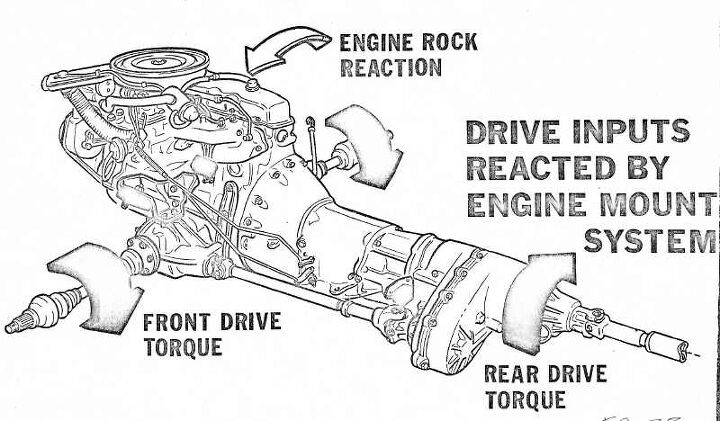

At the rear of the Eagle’s automatic transmission is a single speed NPG119 transfer case which sends power to the front and rear of the car, using a Morse Hy-Vo chain to spin the front driveshaft. The viscous couplings in the transfer case are sensitive to velocity and allow slip between the two driveshafts, allowing them to spin at different speeds. What makes everything work is a fluid made by Dow Corning that some call “silly putty” and others call “honey-like”. It is a “fluid-shear force” silicone fluid that has high shear and heat resistance, allowing consistent performance from 40 below zero to over 400 degrees F. The viscous coupling also provided some anti-skid capabilities because the system tends to equalize driveshaft speeds. The front differential was mounted via a bracket to the left side of the engine crankcase and with the lifted suspension, Lunn and his engineers were able to run the right side half shaft underneath the oil sump, allowing the Eagle to retain the Concord’s independent front suspension.

The net result is that torque is transferred to the axle with the most traction, on wet or dry pavement, or, for the matter, on unpaved roads as well. Though it’s tempting to say that the Eagle was ahead of its time, that idiom is usually reserved for market failures. The Eagle, and later the hatchback Spirit based 4X4 were moderate successes for AMC. Of course the Eagle was indeed ahead of its time, anticipating jacked up station wagons with all four wheels being powered, like the Subaru Forester, the Audi Allroad and the Volvo XC models.

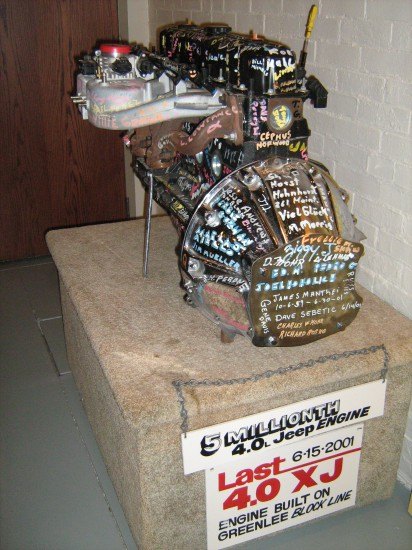

As was his practice, Lunn contributed a technical paper on the Eagle to the SAE. It should be noted that at AMC, he also had a hand in the continued development of what began as the AMC inline six and ended up as the Chrysler Jeep 4.0, an engine whose durability matched that of the XJ Cherokee. Five million of those engines were made.

Wrapping up his career at AMC, Lunn returned to performance cars after Renault bought American Motors. He was named president of Renault Jeep Sport, in charge of all AMC and Renault racing in the U.S. Part of that job involved the design of cars for a low-cost spec racing series in the SCCA. Some of Lunn’s 500 Spec Racer Renaults are still being raced today in NASA, while his basic design is still being used by SCCA’s Spec Racer Ford series. Returning to his rallying roots, in 1984, Lunn was in charge of the first ever American entry in the Paris-Dakar rally.

Lunn retired from American Motors Corp in 1985, but that retirement was short lived as he was immediately named VP of engineering for AMC’s AMC General subsidiary, which made mostly buses and military vehicles. The High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle (HMMWV), better known as the Humvee, progenitor of the Hummer, that AM General had designed for military use was approaching production. The company was running into issues getting the Army to issue acceptance approvals and Lunn’s task was to fix those problems and get the Humvee into production.

After an accomplished career that spanned over four decades, Lunn left AMC for good in 1987, retiring to homes in Florida and later in Italy. As far as I’ve been able to determine, he’s still alive. To be perfectly frank, until I started working on a post about one of the original Gulf Oil livery cars, the Ford GT40 that won at LeMans in both 1968 and 1969, I had no idea of Lunn’s involvement in the project. Had that been the only notable car he worked on, he would have been worth profiling, but as you have seen, the GT40 was just one of a number of Lunn’s historic accomplishments. As TTAC’s managing editor, Derek Kreindler, told me when I pitched him the story, “talk about an unsung hero”. Even as I edited and buttoned up this post, I discovered additional significant contributions that Lunn made, like his involvement with the Jeep 4.0 Six. I’m hard pressed to think of many other engineers that had a role in developing so many historically important cars as Roy C. Lunn did. He’s undoubtedly a car guy you should know about.

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, a realistic perspective on cars & car culture and the original 3D car site. If you found this post worthwhile, you can get a parallax view at Cars In Depth. If the 3D thing freaks you out, don’t worry, all the photo and video players in use at the site have mono options. Thanks for reading – RJS

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, the original 3D car site.

More by Ronnie Schreiber

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- MaintenanceCosts So this is really just a restyled VW Fox. Craptacular tin can but fun to drive in a "makes ordinary traffic seem like a NASCAR race" kind of way.

- THX1136 While reading the article a thought crossed my mind. Does Mexico have a fairly good charging infrastructure in place? Knowing that it is a bit poorer economy than the US relatively speaking, that thought along with who's buying came to mind.

- Lou_BC Maybe if I ever buy a new car or CUV

- Lou_BC How about telling China and Mexico, we'll accept 1 EV for every illegal you take off our hands ;)

- Analoggrotto The original Tassos was likely conceived in one of these.

Comments

Join the conversation

Thanks for the great piece about Roy Lunn---I knew about his role in the AMC Eagle but was not tuned into his earlier roles @ Aston Martin & Ford. Every time I drive my '87 Eagle sedan, I think about how compromised the car is but, at the same time, how it's a great piece of automotive history---and still running strong.

I had the luck to drive an Eagle sedan, and it perplexed people by looking like an ordinary car but was capable of beating the 4x4's of the day. Eagles really did have amazing traction. I was always offended by the Paul Hogan Subaru commercials that shamelessly claimed the first Outback was the "world's first sport utility wagon".