The Man For Whom They Made The Three Million Mile Badge

Most marriages don’t last nearly as long as Irven Gordon’s Volvo P1800 has lasted. And most couples probably don’t spend as much time together as Irv has spent in his beloved car.

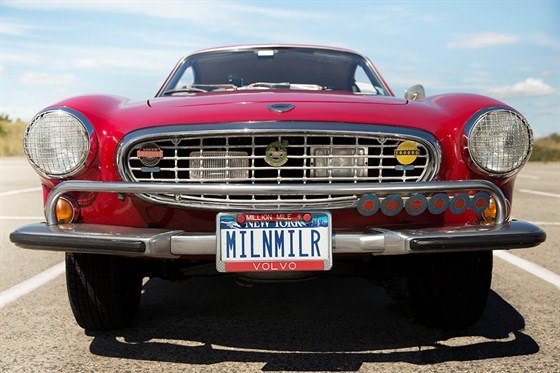

Irv says he hadn’t even heard of Volvos until a few days before he bought the car, on June 30, 1966. At the time, he was fed up with his turbocharged 1963 Corvair Spyder, which he says was constantly making him late for his middle school science teaching job by breaking down en route. While thumbing through a Car and Driver with a car savvy friend, he stumbled upon an ad for the local Volvo dealership, with a photo of a P1800. “These are great cars,” the friend told him. So down he went to Volvoville in Huntington, NY, and took a P1800 convertible for a spin. He drove for three hours, and then bought the much less expensive coupe, for $4,150, or $30,000 in current dollars, approximately his then annual salary.

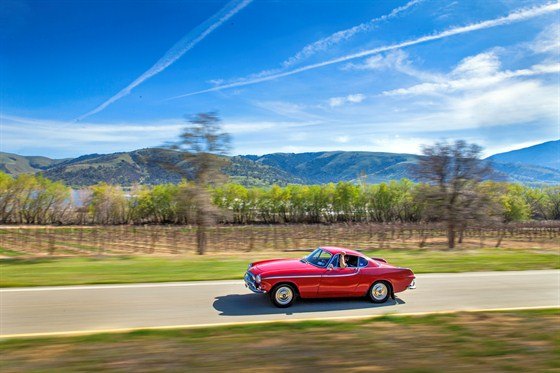

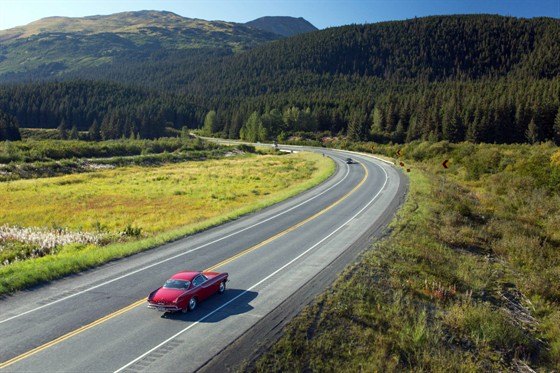

That first weekend, Irv rolled 1,500 miles, returning to the dealership on Monday for his car’s first checkup. He hadn’t planned to drive through the weekend, but he says he was having too much fun to stop—up to Boston, down to Philly, and all over in between before returning to his home on Long Island. He’s been driving the P1800 enthusiastically ever since. On September 24th of last year, he hit 3 million miles.

Irv has averaged 63,000 miles annually—172/day—although that number has ranged from 50k during his teaching years to north of 100k post his 1996 retirement. Assuming an average speed of 45 miles an hour over the years, that’s nearly 4 hours a day. (Irv scoffed at the notion of making such an estimate absent records of speeds traveled over time [see “meticulous,” below]. But for someone who has logged 3 million predominantly recreational miles, frequently crisscrossing the country, but who spent 30 years commuting 125 miles a day on the sclerotic Long Island Expressway—for a total of around 675,000 miles—45 mph seems reasonable to me.)

It takes an exceptionally well-built car to reach 3 million miles. When he opened up Irv’s engine for its second rebuild, “It was in very good shape,” says Duane Matejka, of R Sport Engineering in Pipersville, Pennsylvania. “The valves showed some wear, and the valve seats—that’s expected.” Matejka marvels that the valve springs hadn’t broken after a billion (1,000,000,000) compression cycles. On the bearings, the outer layer of lead had worn down, revealing the underlying copper. Until lead became an official hazmat, the best bearings contained an outer layer of this soft metal, which could absorb any particulates from the oil, preventing them from scoring the bearing surfaces, says Matejka.

In fact, the engine’s major problem 2 million miles after its first rebuild (which his dealer had thought unnecessary, but that Irv had insisted upon because he couldn’t imagine an engine not needing a rebuild at 687K), was a couple of busted piston rings. Matejka says those probably were responsible for the P1800’s lackluster ascent of the Sierras, the symptom that motivated the second rebuild.

The car “is greatly over-designed,” says Matejka, who has a mechanical engineering degree, and who raced a P1800 for many years. The four cylinder “has more bearing area than a Chevy V8.” Matejka says most cars require aftermarket connecting rods to race, but his P1800’s stock rods did the job. These and the crankshaft are forged, which makes them stronger than the more usual casting. Matejka also notes that “the Swedes are anal about their metallurgy.”

The rest of the car is as well-built as the engine. Aside from the first rebuild, the P1800 had only maintenance-related repairs until after it had reached 750k, when the transmission developed an oil leak, says Irv. (Vic Dres, of Goleta, CA, reports that his million mile, ’88 Volvo 740 GLE had no non-maintenance problems until the transmission went kaput after he’d logged half a million miles, and Selden Cooper says his million mile, ’87 240 sedan is still “very reliable.” Neither engine has been rebuilt.)

Nonetheless, there’s more to reaching three million miles than quality. The engine, Matejka says, “was very clean, because [Gordon] is so meticulous,” an adjective others have applied to Irv’s maintenance habits. (In fact, a former student of Gordon’s, Richard Brunswick, MD, who I met at Arlington Mass’s Barismo coffeehouse after he overheard me talking about Irv’s Volvo, praised his teaching in similar terms.)

For example, you’d think a ’66 Volvo, sans garage on Long Island, half a block from the Atlantic, would have rusted out already. My friend, Patty’s 1968 145, originally a California car, which her parents had bought new when she was 10, had sprouted nascent rot by the time she and her husband donated the car to NPR around 2008, after 18 years in the snow belt. When I had wondered why Irv’s was still pristine, he said he hosed the undercarriage during the winter. “I try to get all the crevices, where the salt and sand will build up,” he says. “You just have to get down on your hands and knees.”

Finally, Irv goes easy on the car. Early on, he took part in road rallies, but “after a while, I said, why am I killing my car?” Irv says he accelerates gently, and that his top speed is 60-65 mph. “I like to see how long I can make things last,” he says.

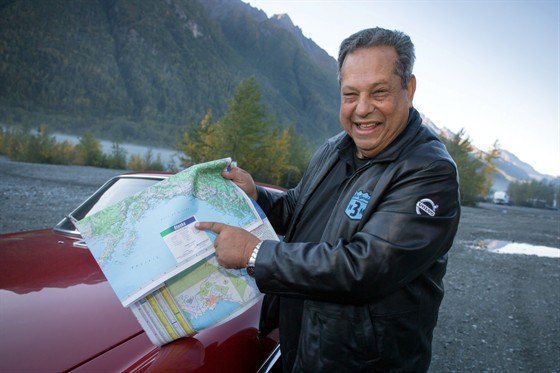

Irv’s love for road trips probably dates from the summer of ’47, when he was 8, and “my family bought a new Buick and spent the entire summer traveling around the US.” Subsequently, whenever his hard-working father had a weekend day off, “we spent the entire day in the car going somewhere.” Irv waxes eloquent about the joy of visiting new places on road trips.

But Irv has driven himself into an uncomfortable paradox. The miles have transformed the P1800 from a fungible commodity into a piece of history—enshrined in the Guinness Book of World Records. That historical status makes the P1800 an asset for Volvo, and for Irv, as well. Since the first million milestone, Irv has been doing ads and events for Volvo, an avocation which he loves, but one for which he swears he receives only expenses (true, says Jessica Snell of the PR firm, Haberman, lately contracted to Volvo). Nonetheless, over the years, Volvo has given Irv two new Volvos—one at the turn of each million miles—with a third on the way.

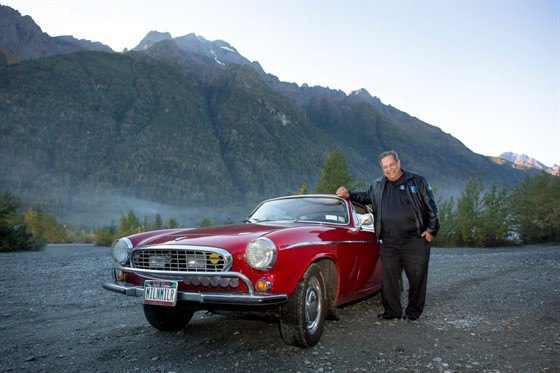

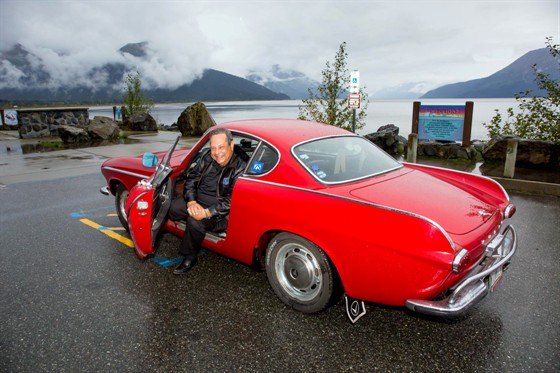

Volvo’s sense of value added was obvious from the shipping of Irv and the P1800 to Alaska for the 3 millionth mile, rather than allowing the event to take place in more mundane environs. Shipping the car was necessary, because by the time Volvo decided to shoot the event in Alaska, “I only had 200 miles to go to reach 3 million,” Irv explains.

All that value has begun to weigh. The odds of a car’s being totaled—a fate Texan Norbert Lissy’s P1800 suffered around 700,000 miles—rise with exposure. In all his driving, Irv says he has never caused a crash, but that the metal has been bent maybe 11 times. A year ago, Irv was headed for Baltimore on a relatively empty I-95, he says, “when a guy in pickup truck ran into my car when I was doing 65. And I was on my way to do film shoot for Google! Ever since then I’m getting to be paranoid.”

And so, nowadays, his other Volvo — the 2002 C70 that he received for the 2 million milestone — is getting more use. “I’m as careful as I can be about where and when I [drive the P1800],” says Irv. Asked if he’d ever sell the P1800, he says, “I just got invited to go to the Brussels auto show. Once I get rid of the car nobody is going to call anymore.”

I'm a freelance journalist covering science, medicine, and automobiles.

More by David C. Holzman

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Oberkanone 1973 - 1979 F series instrument type display would be interesting. https://www.holley.com/products/gauges_and_gauge_accessories/gauge_sets/parts/FT73B?utm_term=&utm_campaign=Google+Shopping+-+Classic+Instruments+-+Non-Brand&utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&hsa_acc=7848552874&hsa_cam=17860023743&hsa_grp=140304643838&hsa_ad=612697866608&hsa_src=g&hsa_tgt=pla-1885377986567&hsa_kw=&hsa_mt=&hsa_net=adwords&hsa_ver=3&gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAjwrIixBhBbEiwACEqDJVB75pIQvC2MPO6ZdubtnK7CULlmdlj4TjJaDljTCSi-g-lgRZm_FBoCrjEQAvD_BwE

- TCowner Need to have 77-79 Lincoln Town Car sideways thermometer speedo!

- Kjhkjlhkjhkljh kljhjkhjklhkjh I'd rather they have the old sweep gauges, the hhuuggee left to right speedometer from the 40's and 50's where the needle went from lefty to right like in my 1969 Nova

- Buickman I like it!

- JMII Hyundai Santa Cruz, which doesn't do "truck" things as well as the Maverick does.How so? I see this repeated often with no reference to exactly what it does better.As a Santa Cruz owner the only things the Mav does better is price on lower trims and fuel economy with the hybrid. The Mav's bed is a bit bigger but only when the SC has the roll-top bed cover, without this they are the same size. The Mav has an off road package and a towing package the SC lacks but these are just some parts differences. And even with the tow package the Hyundai is rated to tow 1,000lbs more then the Ford. The SC now has XRT trim that beefs up the looks if your into the off-roader vibe. As both vehicles are soft-roaders neither are rock crawling just because of some extra bits Ford tacked on.I'm still loving my SC (at 9k in mileage). I don't see any advantages to the Ford when you are looking at the medium to top end trims of both vehicles. If you want to save money and gas then the Ford becomes the right choice. You will get a cheaper interior but many are fine with this, especially if don't like the all touch controls on the SC. However this has been changed in the '25 models in which buttons and knobs have returned.

Comments

Join the conversation

test comment with image

Test image