In Search Of… Understeer

The Chevy’s steering is light and reacts quickly on turn-in. Handling eventually gives way to understeer…

Hmm. Is this a review of the Corvette Z06 Carbon? The new Camaro ZL1? Perhaps a lucky journalist has been permitted to hack a C6.R around Road Atlanta for a few laps? Nope, it’s from Car and Driver‘s recent powder-puff piece on the 2012 Sonic.

You know, the Sonic. The fourteen-thousand-dollar subcompact.

Handling, apparently, “eventually gives way to understeer” in a fourteen-thousand-dollar subcompact. Amazing. I’d figured there would be some kind of hideous snap-oversteer swing-axle murderball hidden inside that bitch. What a joke. Here’s a hint: any time a writer appears to be surprised by understeer in a modern mass-production street car, assume that writer is a moron and close your browser page lest you accidentally catch the stupid through a dirty keyboard or something.

‘Twas not always the case, however. In this article, and a sequel to follow shortly, we will discuss a few things: what understeer really means, why you want it, why it is now the default handling behavior for all “regular” cars, and how making it the default handling behavior is accomplished. Boring stuff, sure — but when you’re done reading it, you will be more qualified to review the Chevrolet Sonic’s handling than the guy who actually got paid to do it.

What is understeer, anyway? The authentic definition is a little bit more complex than we’d like to think, unfortunately. We have to start with the actual mechanics of how a car turns. Imagine that you are driving down the road in a straight line, and that the road on which you are driving is completely level. If you turn the steering wheel, a series of gears, shafts, and joints will cause the angle of the front wheels to change. (Note: you’re not guaranteed to get the same amount of angle on both wheels.)

The wheels will turn and the tires, which are mounted on the wheels, will also turn, although not quite as much. The difference between the amount of angle in the wheels and the amount of angle in the tires is mostly a function of sidewall stiffness and height, plus the height and stiffness of the tread blocks. The more flex you have in the sidewall, the bigger the gap. This is easy to understand, right?

Forcing the tires to approach the road at an angle causes friction, which pushes the front end of your car in the direction you’ve chosen. Naturally, this being all physics-like and complicated, the amount of turn you get never equals the amount of angle you’ve put in the tires. The difference — “slip angle” — is a function of tire traction, road surface, and so on, and it causes heat to build up in the tires. Track time melts tires because of slip angle, not because you’re, like, totally going fast and stuff. High-speed driving, like on the fabled autobahn, does build up heat, but it takes a while to do it. You can run 112-mph rated snow tires to 160mph if you don’t spend more than a moment or two at that speed. I know this, because I’ve done it.

The dictionary definition of “understeer” doesn’t actually exist, but if it did, it would say something like “not getting all the change in direction you’ve requested via the steering wheel.” If you understood the above paragraphs, then you’ve already realized that understeer happens all the time in pretty much every car, every time you turn the steering wheel. Even a Formula One car begins the entry into a turn by “understeering”. Nobody gets all the steer they asked for. That’s physics. Tall tires, complacent sidewalls, and rubber bushings in the suspension just exacerbate the effects.

Most drivers compensate pretty quickly for that built-in understeer after the first few minutes spent driving a car. Unless you’re going from a Lotus to a U-Haul truck, you probably don’t even consciously consider the process. So let’s put “built-in” understeer aside.

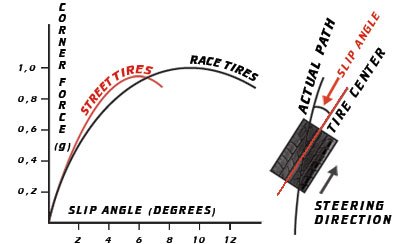

Tires, like sophisticated women, don’t respond well to a heavy or inept hand. Each tire has a bell curve of available traction. As you ask for more traction, you get more, until you pass a certain point, and then each additional steering input produces less traction. This graphic explains the concept… I hope.

Note how turning the wheel past a certain point produces less traction. This accounts for the phenomenon known as “the dipshit limit”, which I have observed at many, many press events. It works like this:

- Journalist approaches corner “going real fast”.

- Journalist cranks the living hell out of the steering wheel.

- Understeer occurs.

- Journo complains about “heavy understeer at the limit” in print publication.

- The cat, bird, or homeless person using the print publication to catch their defecatory material briefly catches sight of such assertion and is quite confused.

Using our graph below, we could see that the typical street tire wants six degrees of steering/slip angle — but our journalist immediately dials-in eight or nine. The result? The car doesn’t handle. A skilled driver would carefully dial-in an amount of steering which corresponds very closely to the maximum amount of traction available from the tire set he or she is using.

There’s another way to generate excessive understeer in a car — use the brakes at the same time. A tire has a fixed amount of traction, and it can use that traction in any direction. Keith Code, the motorcycle writer, called it the “dollar theory”. You can spend a dollar braking, or cornering, or accelerating — but if you combine the inputs, you may not like the results. Many of my fellow journos enter the turn with a foot jammed onto the brake, while they are turning. If you’re using fifty cents’ worth of braking, don’t expect to get more than fifty cents’ worth of turn.

When we combine the two mistakes, it’s easy to see why most cars feel like “understeering pigs” to journalists. They are putting way too much steering into the car, and they are braking while entering the turn. Happens again and again. At any press event where a racetrack is provided, you will see brake lights on all the way through the turns. No wonder they aren’t going very quickly.

How do we mitigate understeer? The easiest way: Get your braking done before the turn. (Trail-braking is something we will discuss another time.) When you turn in, dial your input in slowly and precisely, noting the amount of resistance you’re getting back. If you’re driving an unfamiliar car, turn the wheel until the amount of resistance lessens a bit, then dial back just a touch. You may not be “at the limit” but you won’t be far, either. Try not to hit anything.

In the next article, we will talk about why street cars used to oversteer by default, how that changed, and why that’s a good thing for everybody.

More by Jack Baruth

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Cprescott Remember the days when German automakers built reliable cars? Now you'd be lucky to get 40k miles out of them before the gremlins had babies.

- Cprescott Likely a cave for Witch Barra and her minions.

- Cprescott Affordable means under significantly under $30k. I doubt that will happen. And at the first uptick in sales, the dealers will tack on $5k in extra profit.

- Analoggrotto Tell us you're vying for more Hyundai corporate favoritism without telling us. That Ioniq N test drive must have really gotten your hearts.

- Master Baiter EV mandates running into the realities of charging infrastructure, limited range, cost and consumer preferences. Who could possibly have predicted that?

Comments

Join the conversation

Interesting article, I'm convinced that most people who talk about understeer & oversteer have never experienced either, at for most of those who have it resulted in a crash. Re the "dipshit limit", this can bee seen on in-car footage (eg VBH on Fifth Gear) when the car suddenly darts in the direction of the turn as the steering lock is eventually unwound and the tyre climbs back up the steering input curve shown above.

When do we get part 2?