1965 Impala Hell Project, Part 8: Refinements, Meeting Christo's Umbrellas

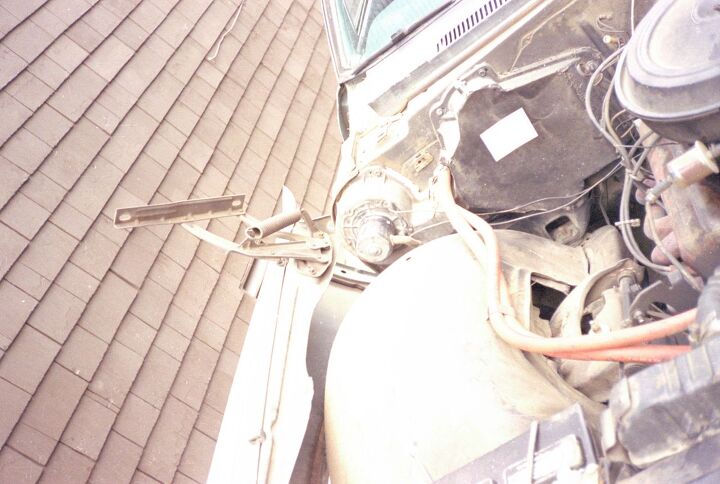

I’d enabled the heater by fashioning a block-off plate to cover the torn-out evaporator core housing, which made my second winter with the car much more pleasant… but then the blower motor’s bearings started to scream. 26 years out of a part that The General’s low-bid supplier probably charged $1.04 for wasn’t too bad, but I’d become spoiled after a few months of not being forced to wear several grunge-grade flannel shirts while driving.

In case you were wondering what happened to the Impala’s original air-conditioning gear, I’d given all the parts to my friend Paul (who provided invaluable help during the 283-to-350 engine upgrade in the summer of ’90). He ended up knocking together this Field Expedient Engineering AC setup in his ’67 Mustang, using a weird mashup of 1965 Impala and 1980 Fiat Brava climate-control components. This rig gave the Mustang meat-locker temperatures on even the hottest Anaheim days, though it did have a tendency to spray condensation all over the passenger.

Since this generation of full-sized Chevrolet was designed to be bashed together by a bunch of dudes who started each shift with a six-pack of Country Club apiece, I figured the heater blower fan would be easily accessible. Sure, it was accessible on the assembly line, before the fenders and hood were installed, but it turned out to be a serious pain in the ass on a complete car. Not anywhere near as bad as replacing the heater core on a Volvo 240, mind you (if the heater core in your 240 goes bad, my advice is to scrap the car), but way more work than I’d expected.

The replacement blower motor was under 20 bucks new (and still is, 20 years later), so I decided to splurge and avoid the junkyard-parts route this time.

Aaaah, the pleasure of driving in winter without bundling up like the Michelin Man!

Replacing the sagging rear springs, along with new front ball-joints and control arm bushings, solved most of the car’s wandering-in-freeway-lane problems. However, the completely played-out shock absorbers— no doubt installed by Manny, Moe, and Jack in about 1979— made the car way too bouncy and ill-handling. I scored a full set of new KYB Gas-A-Justs on sale at Lee Auto Supply, and the car started taking the turns in semi-modern fashion.

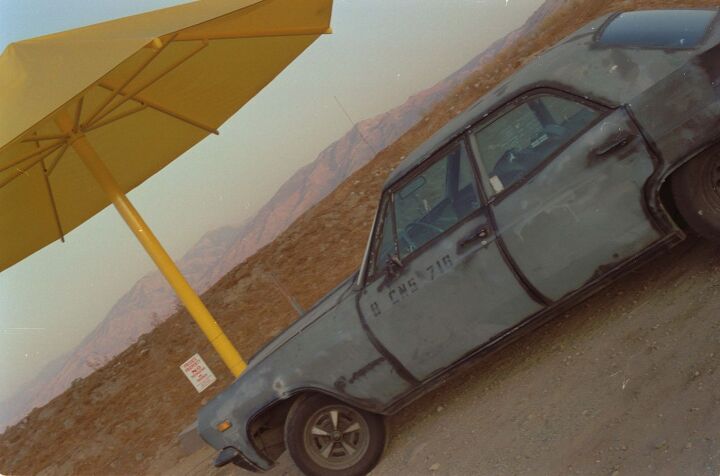

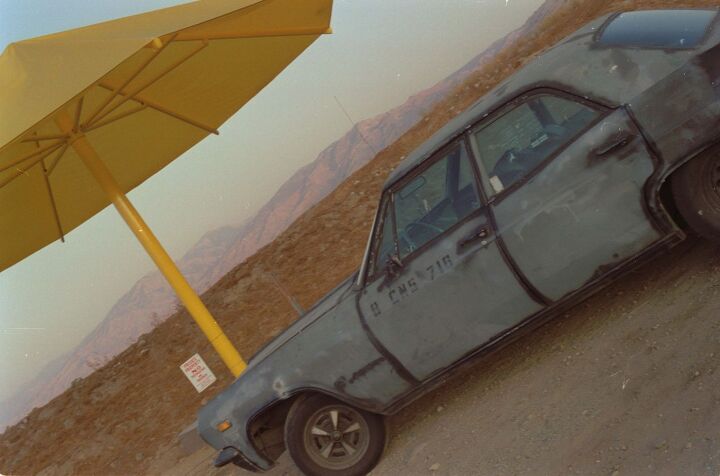

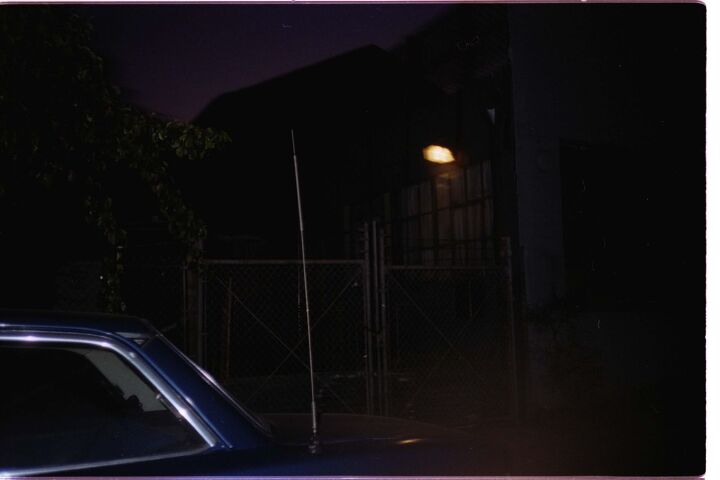

Applications of various shades of gray and black primer paint, plus the normal patina acquired when you never wash a car during coastal California’s dry season, were really helping me achieve the look of the art car I’d had in mind all along.

Around this time, I’d become more serious about photography in general and hacked-up thrift-store cameras in particular. I’d been bulk-loading my own Kodak Tri-X 35mm (film of choice for generations of news photographers), and I’d discovered that you could pry open the early disposable cameras and reload them with your own film. Just the thing for gloomy winter shots of the Impala with skeletal trees and a Pinto wagon!

The car was really starting to look exactly the way I’d envisioned the project when I bought the car; the glossy industrial-gray paint that a previous owner had hosed over the original Tahitian Turquoise had been transformed into a gritty urban camouflage with texture.

I’d load the car up with disposable cameras, pinhole cameras, $2.99 panorama cameras, and so on and take it out on long photographic expeditions. At night, I’d set up a darkroom in the bathroom and huff Dektol for hour after hour.

It wasn’t a bad life, but the ongoing early-1990s recession and the Vietnam/Watergate/Energy Crisis experiences of my formative years made it clear to me that I’d spend the rest of my life working a series of shit jobs while The Downpresser Man drank the big champagne and laughed. Eventually, The Downpresser Man would round up everyone who didn’t have at least $10 million in his or her bank account and ship them off to shovel radioactive uranium-mile tailings in the Spiro Agnew Memorial Re-Education Facility in the Utah desert. In the meantime, I was going to enjoy driving my Impala.

My long-suffering parents were cool about me and my wretched car staying at their place when my various 10-slackers-in-squalid-apartment living situations fell through, and so I helped them out by re-foundationing and reinforcing the 1880-stable-turned-useless-garage in their back yard; a dim-witted do-it-yourselfer had destabilized the structure by installing a half-assed garage door in the 1950s, and the ’89 earthquake had come within seconds of knocking the whole thing down. By the time I got to the project, the entire building was being supported by two come-alongs stretching steel cables diagonally from corner to corner.

Still, I had to put in my time in The Downpresser Man’s salt mines. There were exactly zero real jobs available in California for recent college grads during the early 1990s, but temp agencies had a vast assortment of low-pay/low-prestige gigs available. Since I could type 60 WPM and lift 150 pounds, I qualified as both office temp and light-industrial temp. This meant that, one day, I might find myself in a tie and shiny black shoes, filing medical records or answering the phone in some grim, fluorescent-lit veal-fattening pen… and the next day I might be stacking boxes of laundry detergent at a soap factory. For one two-week period, I drove fresh-from-Japan, plastic-wrap-protected 1992 Honda Del Sols the two miles from the Port of Richmond docks to the yard where they were loaded onto train cars and transporter trucks. Hundreds, thousands of Del Sols; I became expert in filling the 30 seconds while the other temps climbed into their Del Sols by finding the radio security code (remember those?) in the glovebox, entering it into the stereo, and finding some gangster-rap or metal song to blast during the five-minute drive from the docks.

The Impala didn’t cause any real problems when I showed up for light-industrial temp jobs, since most of my fellow temps drove equally grimy-looking machinery, but managers at office-temp gigs usually ordered me to park my car far, far from the premises. That meant that I didn’t have time to walk to and from my remotely-parked car to enjoy some blissful solitude during lunch breaks; instead, I had to endure the slow death of office gossip in the break room. Fortunately, most office lifers ignore temps and I wasn’t required to participate in conversations.

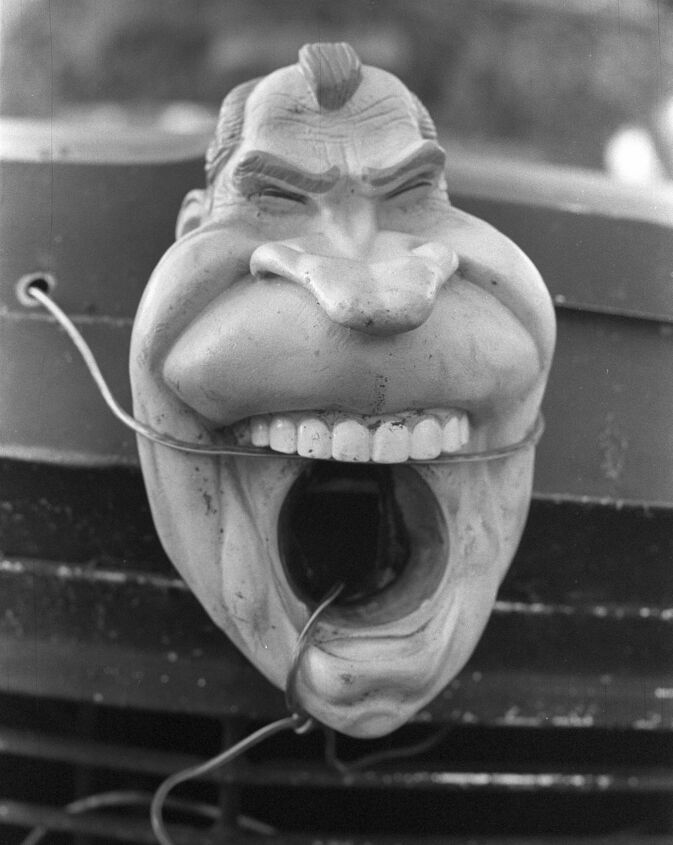

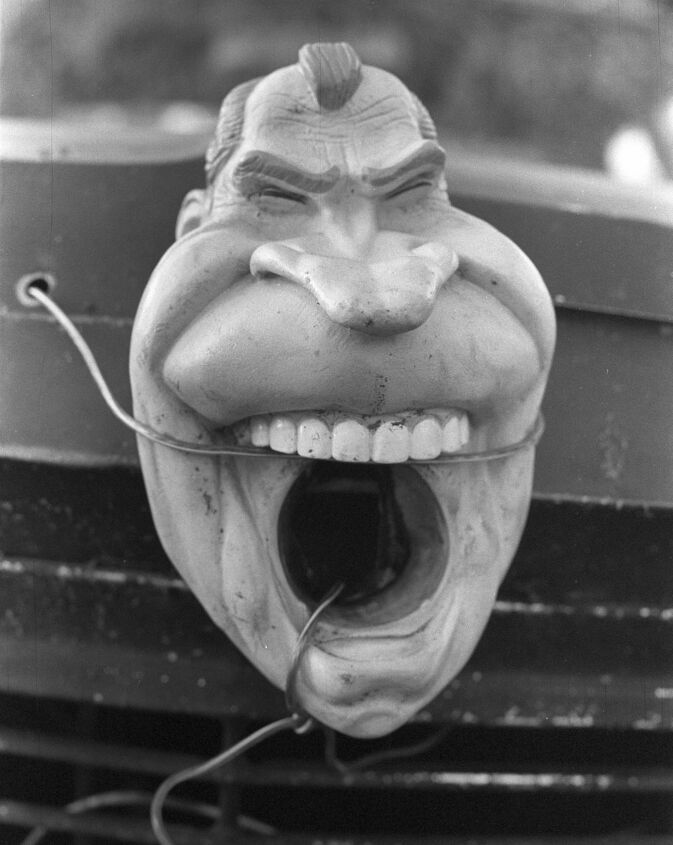

Around this time, I obtained this very expressive Richard Nixon hood ornament (originally intended for installation over one’s shower nozzle, so that a shower feels like Nixon is spitting on you) and wired it to the Impala’s grille. I’ve spent most of my life obsessed with the Son of Orange County (a digression far too lengthy to get into here), and so the Tricky Dick hood ornament just felt right.

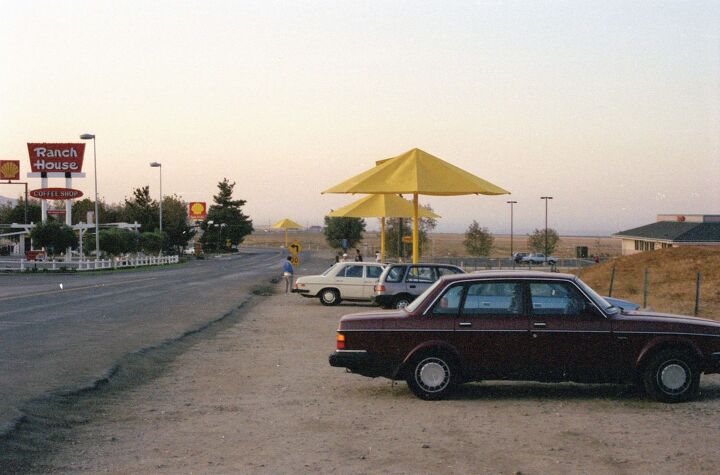

The Impala had become an excellent long-distance road-trip car, comfortable and reliable. Late in 1991, I headed south on Interstate 5 in order to do some sort of meta-art-car installation with a much more famous work of public art.

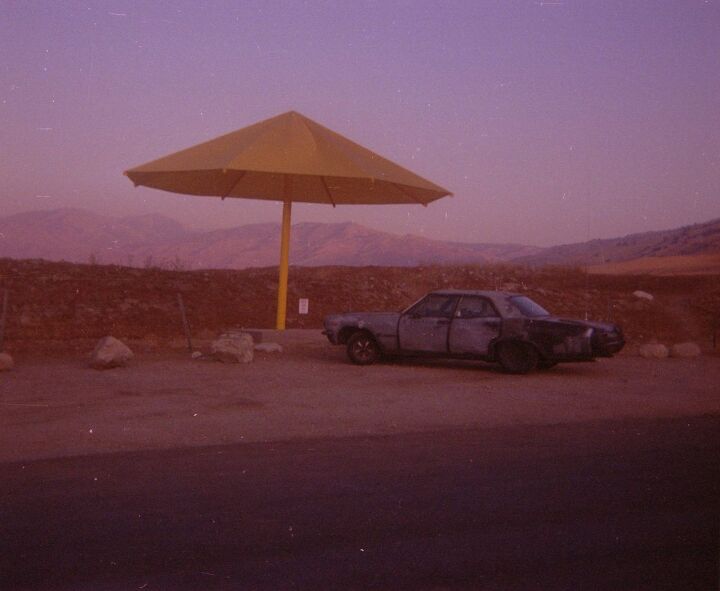

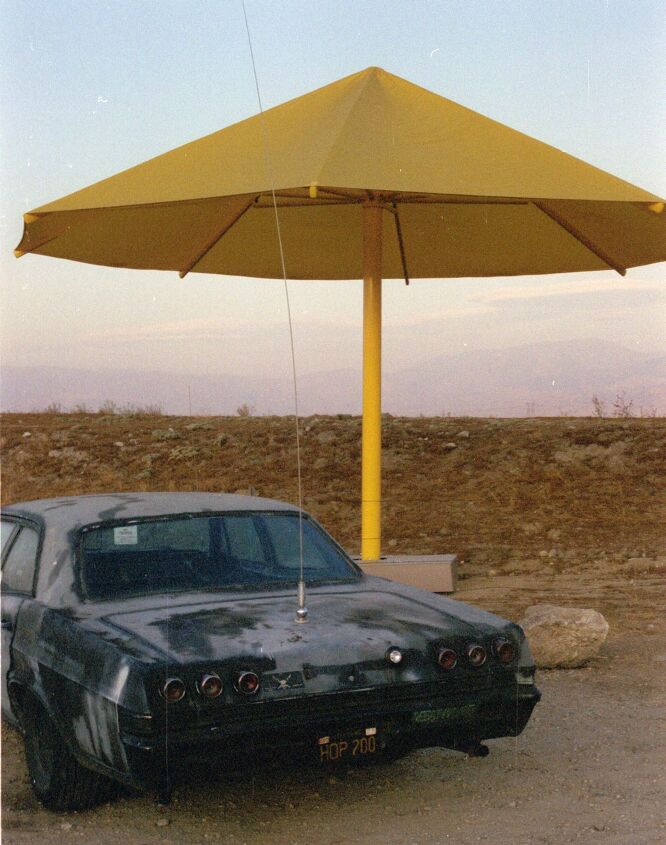

On October 9, 1991, Christo and Jean-Claude’s 3,100 gigantic umbrellas were opened up along inland valleys, one in Japan and one in the United States.

Christo’s American umbrellas were set up along the Grapevine portion of Interstate 5 (immortalized as the setting for “Hot Rod Lincoln”), about 75 miles north of Los Angeles.

At the time, you could still get 126 film, and I shot a lot of grainy, blurry photos on 50-cent-at-yard-sales Instamatic cameras. Nowadays, you just use an app in your phone’s camera to get terrible shots like this.

But you can’t get Flash Cubes for your iPhone!

After visiting the Christo Umbrellas, I headed south to visit my friends at UCI’s Irvine Meadows West trailer park.

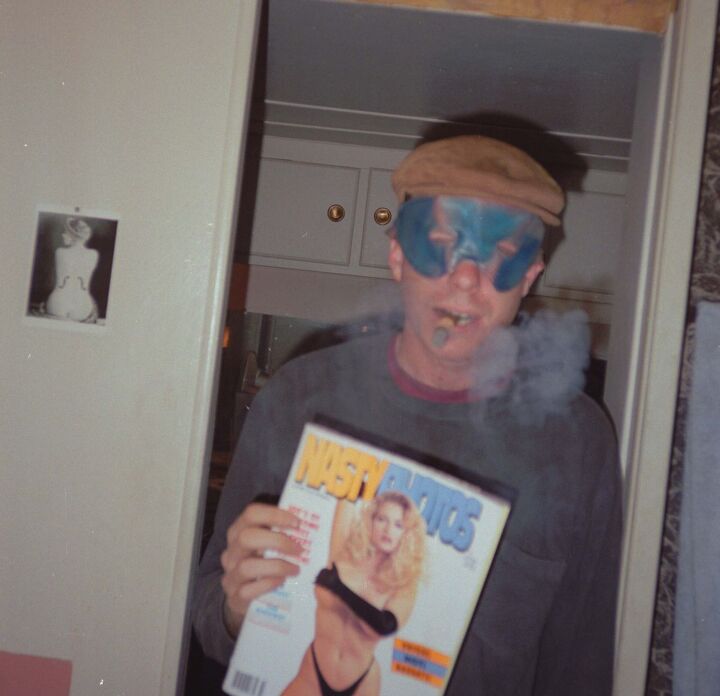

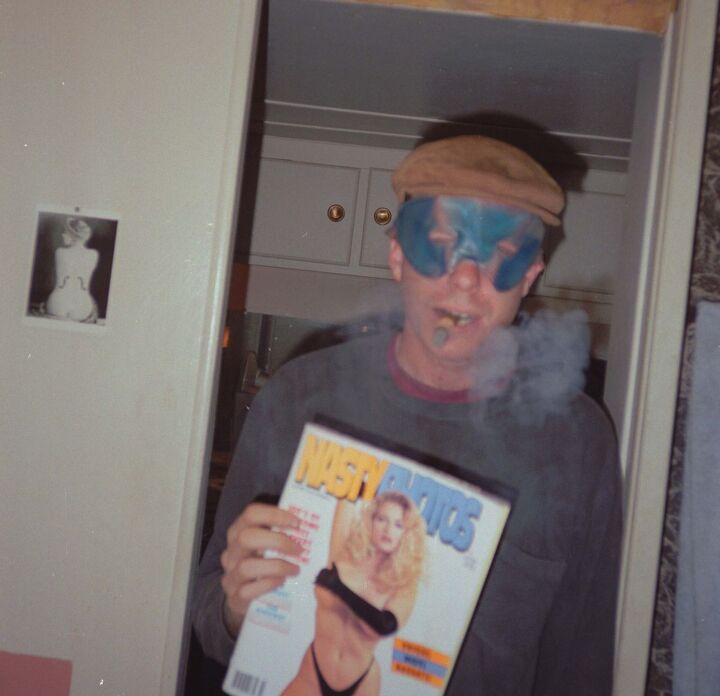

Incomprehensible rituals were still the order of the day at IMW.

The Impala’s back seat, a ’66 Caprice unit I’d found in near-perfect condition for cheap in The Recycler, proved to be most comfortable for road-trip sleeping.

On the way back north, I visited The Umbrellas again. By this time, high winds had toppled some of the umbrellas, killing a woman and injuring several others, and Christo dismantled them soon after.

Time to head back to The Downpresser Man’s offices and warehouses. Next up: Shoulder belts, bailing from academia.

Introduction • Part 1 • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4 • Part 5 • Part 6 • Part 7 • Part 8 • Part 9 • Part 10

Murilee Martin is the pen name of Phil Greden, a writer who has lived in Minnesota, California, Georgia and (now) Colorado. He has toiled at copywriting, technical writing, junkmail writing, fiction writing and now automotive writing. He has owned many terrible vehicles and some good ones. He spends a great deal of time in self-service junkyards. These days, he writes for publications including Autoweek, Autoblog, Hagerty, The Truth About Cars and Capital One.

More by Murilee Martin

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- SCE to AUX Range only matters if you need more of it - just like towing capacity in trucks.I have a short-range EV and still manage to put 1000 miles/month on it, because the car is perfectly suited to my use case.There is no such thing as one-size-fits all with vehicles.

- Doug brockman There will be many many people living in apartments without dedicated charging facilities in future who will need personal vehicles to get to work and school and for whom mass transit will be an annoying inconvenience

- Jeff Self driving cars are not ready for prime time.

- Lichtronamo Watch as the non-us based automakers shift more production to Mexico in the future.

- 28-Cars-Later " Electrek recently dug around in Tesla’s online parts catalog and found that the windshield costs a whopping $1,900 to replace.To be fair, that’s around what a Mercedes S-Class or Rivian windshield costs, but the Tesla’s glass is unique because of its shape. It’s also worth noting that most insurance plans have glass replacement options that can make the repair a low- or zero-cost issue. "Now I understand why my insurance is so high despite no claims for years and about 7,500 annual miles between three cars.

Comments

Join the conversation

Another great read! Can't wait for the next!

Fuck. I keep telling myself that TG USA is getting better and Murilee keeps reminding me that TG USA didn't hire the kind of people that would have made me actually love the show.