Review: 2011 Hyundai Equus

Just two years ago the $40,000 Genesis was an audacious step upmarket for Hyundai. Tepid sales of the semi-premium line suggest that the market still isn’t quite ready for an expensive car from Korea. And yet, for 2011, the company is attempting an even larger leap with the $58,900 Equus ($65,400 in Ultimate trim). This is territory into which even storied manufacturers like Cadillac and Lincoln fear to tread (with cars at least). Does Hyundai’s large premium sedan come close enough to established competitors, while undercutting them enough in price, that potential buyers will overlook the badge? Or is it a step too far too soon destined to sell in very small numbers?

While the Genesis targets the E-Class, 5-Series, and Lexus GS, the Equus goes after their larger siblings. The dimensional relationship between the two senior Hyundais most resembles that between the BMW 5 and 7, with a roughly four inch difference in wheelbase (119.9 inches for the Equus), seven inch difference in length (203.1), one inch difference in width (74.4), and negligible difference in height (58.7).

Unlike with the BMWs, though, the Equus doesn’t simply look like the same sausage in a longer length. With generous curves befitting a Buick—even a sweep-spear—the Equus’ exterior has more style and is less derivative (of direct competitors at least) than that of the Genesis. Yet, as the domestic car of choice for home market executives, it remains much more conservative than the Sonata. There’s nothing here that will turn buyers off. But there’s also nothing much to turn them on.

The interior styling, with no distinctive eye-catching elements, is more generic premium sedan. The materials are mostly worthy of the price, but don’t surprise—unless the presence of copious amounts of Alcantara suede (for the headliner), premium leather (on the instrument panel as well as the seats), and real wood inside a Hyundai surprises. Scads of high-end features are standard, including adaptive cruise control, quad-zone temperature control, power reclining rear seats, a 608-watt, 17-speaker Lexicon audio system, and (the car’s best claim for a “first”) an iPad for the owner’s manual. A plus: the plentiful controls needed to operate all of these features are easier to learn and operate than those in competing European sedans. As in uplevel Mercedes, metaphoric seat controls are located high on all four doors.

Unfortunately, Hyundai neglected the basics in its rush to pack the Equus full of features. The driver’s seat, positioned high relative to the instrument panel like those in the Lexus LS and Mercedes S-Class, provides a good view forward through the comfortably upright windshield and reduces the perceived bulk of the car. But the seat itself fails to provide even a hint of side support. The bolsters are very far apart, and the space between them is bereft of contour. Hardcore lateral support is neither needed nor expected—this is not a sport sedan—but more cosseting seats would be much more comfortable even when cruising the straightest highway.

The front seats are also responsible for a serious shortcoming in the rear seats. To begin with, despite its larger exterior the Equus isn’t significantly larger than the Genesis on the inside. Combined, front and rear legroom grow by only 1.1 inches, to 45.1 and 38.9 inches, respectively. Though these are very competitive numbers, the spec sheet doesn’t always accurately represent real life. And in real life, because there’s no space for feet beneath the front seats (even when they’re raised), rear legroom is in short supply. I’m 5-9, and have a shortish 30-inch inseam, but could not comfortably sit behind myself. With my feet unable to slide forward beneath the front seats, I had to sit “knees high,” thighs unsupported. The rear seat of the Genesis seems roomier and more comfortable. Power reclining rear seats are standard on the Equus, but this feature shifts the seat bottom forward, making a bad situation worse. Also, even with the rear seat in its full upright position I found it overly reclined.

Step up from the Equus Signature to the Equus Ultimate (trim names borrowed from the Lincoln Town Car?) and a power legrest is added to the right rear seat. Oddly, unless you’re under 5-6 there’s not enough space to use it, even with the front right seat motored all the way forward and tipped. Hyundai offers an extended wheelbase Equus in Korea. The legrest should have been restricted to that car. A shame, because the Ultimate’s rear console (in place of the Signature’s center seating position) includes the makings of a thoroughly executive experience, with a refrigerated storage compartment, DVD entertainment system, and plenty of buttons to play with. Who knew Hyundai could be so cruel, providing so many toys but not enough room to play.

The Equus shares its 385-horsepower 4.6-liter V8 and six-speed automatic with the Genesis, but weighs nearly a quarter-ton more (4,449 to 4,592 pounds). Consequently, acceleration is easily adequate, but not exhilarating (it’s not that sort of car, anyway) or effortless. The engine isn’t silent, but the noises it makes are welcome to anyone with even the slightest care for driving. Want more scoot? Wait a year, when Hyundai will replace the 4.6 with a direct-injected 5.0-liter good for 429 horsepower and add two ratios to the transmission. The 2012 powertrain should also be good for another MPG. The EPA rates the 2011 for 16 city, 24 highway. Aside from 6 MPG during a vigorous exploration of the chassis, I observed slightly better numbers, and even exceeded 30 on one stretch of rural highway with a few complete stops.

The Equus’ standard suspension pairs height-adjustable air springs with adaptive shocks. Lexus, and not anything from Europe, was clearly the dynamic target. The Korean flagship’s electro-hydraulic steering isn’t sloppy, but is light at all speeds—it doesn’t firm up on the highway–and body motions verge on floaty. But emphasis on “verge”—this is no land yacht of yesteryear. Though even a Lexus LS steers and handles more intuitively, for a comfort-oriented luxury sedan there’s sufficient composure and control.

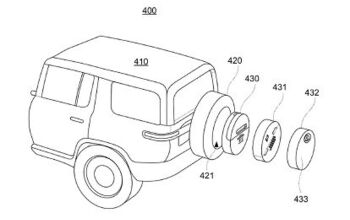

Mysteries abound. A “sport” button on the center console allegedly firms things up, but you’ll be hard pressed to detect a difference. Also making no apparent difference, no matter how long they are held down: the buttons to deactivate the stability control and VSM (which integrates the stability control with various other safety systems). Even with two lights in the instrument cluster announcing that both nannies have been furloughed, the stability control intervenes early, often, and aggressively. Oversteer ain’t happening. Give the engine too much gas in a corner, and exit with too little. The point of the large staggered tire sizes, 245/45R19 up front, 275/40R19 in back? Unclear.

The Equus rides smoothly and quietly, but competitors are smoother and quieter. Slight tremors unbecoming a premium sedan can be felt through the steering wheel even though not much else can. In ride as in handling, the chassis is good enough that the typical buyer will be satisfied, but not great. The Equus doesn’t come close to setting new standards for refinement the way the Lexus LS did 21 years ago. In Hyundai’s defense, these standards are now so lofty that even approaching the class norm on the initial attempt is quite an achievement.

Lesser Hyundais are no longer much less expensive than competitors, with a ten-percent price advantage typical. The Equus starts out a little over ten percent below the Lexus LS 460, $58,900 vs. $66,255. But nearly $10,000 in options are needed to equip the Lexus like the base Hyundai. And even then the Hyundai has roughly $2,000 in additional features, according to TrueDelta’s car price comparison tool. Adjust for these differences, and the Equus has a price advantage of over $19,000. Compare the Equus to a BMW 750i, and this advantage more than doubles. If a $60,000 car could ever count as a bargain, this is it.

The Ultimate, on the other hand, fails the value test. It includes about $3,000 in additional features, but given the shortcomings of the rear seat these are of dubious real-world utility. And they add $6,500 to the price.

Not part of these value calculations: Hyundai’s strategy for making its dealers viable purveyors of $60,000+ automobiles. This strategy: the customer never has to risk tripping over an Accent by visiting the dealership (though a special Equus section must be set aside just in case one does). If you’re a potential buyer, they’ll bring the Equus and paperwork to you. And, whenever the car needs service they’ll retrieve it and return it, leaving either a Genesis or Equus as a loaner in the interim. Sound expensive? Well, during the first five years it’s all free.

The Hyundai Equus looks and performs decently enough, and offers an industry-leading cornucopia of standard features at a much lower (if still far from low) price. So, even though it doesn’t break any new ground, Hyundai’s finest would be worth serious consideration by anyone for whom $20,000 isn’t pocket change, except for one thing: the seats. How could Hyundai put so much obvious effort into this car, then include such unsupportive front seats with no room beneath them for the rear seat passengers’ feet? Did none of the many people involved in the development of the car notice these major shortcomings? Certainly everyone involved could not have been under 5-6 and over 300 pounds. The American senior executives are downright tall. What happened? Better to look forward. Hyundai has demonstrated a willingness to quickly change what needs changing. So maybe next year.

Hyundai made this vehicle available for review at a ride-and-drive event.

Michael Karesh owns and operates TrueDelta, an online source of automotive reliability and pricing data

Michael Karesh lives in West Bloomfield, Michigan, with his wife and three children. In 2003 he received a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. While in Chicago he worked at the National Opinion Research Center, a leader in the field of survey research. For his doctoral thesis, he spent a year-and-a-half inside an automaker studying how and how well it understood consumers when developing new products. While pursuing the degree he taught consumer behavior and product development at Oakland University. Since 1999, he has contributed auto reviews to Epinions, where he is currently one of two people in charge of the autos section. Since earning the degree he has continued to care for his children (school, gymnastics, tae-kwan-do...) and write reviews for Epinions and, more recently, The Truth About Cars while developing TrueDelta, a vehicle reliability and price comparison site.

More by Michael Karesh

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- TheEndlessEnigma Of course they should unionize. US based automotive production component production and auto assembly plants with unionized memberships produce the highest quality products in the automotive sector. Just look at the high quality products produced by GM, Ford and Chrysler!

- Redapple2 Got cha. No big.

- Theflyersfan The wheel and tire combo is tragic and the "M Stripe" has to go, but overall, this one is a keeper. Provided the mileage isn't 300,000 and the service records don't read like a horror novel, this could be one of the last (almost) unmodified E34s out there that isn't rotting in a barn. I can see this ad being taken down quickly due to someone taking the chance. Recently had some good finds here. Which means Monday, we'll see a 1999 Honda Civic with falling off body mods from Pep Boys, a rusted fart can, Honda Rot with bad paint, 400,000 miles, and a biohazard interior, all for the unrealistic price of $10,000.

- Theflyersfan Expect a press report about an expansion of VW's Mexican plant any day now. I'm all for worker's rights to get the best (and fair) wages and benefits possible, but didn't VW, and for that matter many of the Asian and European carmaker plants in the south, already have as good of, if not better wages already? This can drive a wedge in those plants and this might be a case of be careful what you wish for.

- Jkross22 When I think about products that I buy that are of the highest quality or are of great value, I have no idea if they are made as a whole or in parts by unionized employees. As a customer, that's really all I care about. When I think about services I receive from unionized and non-unionized employees, it varies from C- to F levels of service. Will unionizing make the cars better or worse?

Comments

Join the conversation

The car is definitely a value. But people buying these cars aren't looking for value. They are badgewhoring. http://www.epinions.com/content_536572628612

ALL silver painted plastic trim pieces in ALL car interiors must die, ASAP. The sooner, the better.