Scents and Sensibility

At the end of my local car wash, the Peruvian supervisor offers customers a choice of air fresheners. The battered spray bottles are hand-labeled: watermelon, cherry, vanilla, pine, apple, strawberry, lemon, pina colada and new car smell. Needless to say, the scents are about as authentic as a velveteen Last Supper. The idea that someone would actually choose to submit their nostrils to such an egregious olfactory attack is a source of constant wonder. But hey, Ford still sells Thunderbirds, so I guess there's no accounting for taste.

Maybe people first turn to these synthetic fragrances because their new cars smell so nasty. I recently drove a box-fresh Ford Five Hundred. Even before I turned the key, every nerve, cell and fiber of my body told me that I was sitting in a fantastically cheap car. It smelled awful, like a $20-a-night motel room sanitized with porno strength ammonia. The so-called "top note" was pure adhesive, pungent enough to get an underage passenger arrested for glue sniffing. The "bottom note" was, well, there wasn't any. And this was the top-spec, leather-lined SEL version.

The newly-minted Pontiac G6 that arrived on my driveway was worse. The cabin emitted a nostril-curling sour glue odor that made my hand reach for the electric window button faster than if I'd thrown a dead skunk in the back seat. When my step-daughter added that distinctive odor known as a McDonald's happy meal, my nose wasn't. If someone had smoked a cigarette in the car, I would have been forced to Google "nosegay".

Of course, both cars will mellow with the miles; the out-gassing of the offending volatile organic compounds (VOC's) will dissipate as the construction materials settle into adolescence. Eventually, the Ford and the Pontiac will reveal their owners' habits, rather than their manufacturer's suppliers.

That still leaves a lingering mystery: why do car companies ignore this critical characteristic of their automotive products? They spend billions appeasing the gods of NVH (Noise Vibration and Harshness) and not a nickel to try and make their cars' interiors smell at least as appealing as a sheet of Bounce fabric softener.

The feel-good factor created by upmarket smells simply can't be underestimated. The Continental GT is a fine car, but the German machine would not wear the Bentley crest so easily if it weren't for the deep, rich leather smell leaching out of every nook and cranny of its cow-covered interior. The odor is a direct shot to the brain, constantly whispering "money, money, money". The GT could have Passat internals and still literally reek of class.

As companies like Ford and Buick try to take their products upmarket, or try to find a brand-specific competitive advantage, they would do well to address the smells coming from their malodorous machines. Adding or prolonging that "new car smell" is not enough; most people can tell the difference between slatherings of cheap adhesive and the judicious use of more premium materials. Fitting a leather interior is also insufficient; properly fragrant leather is an expensive business and most post-manufacturer treatments are dire. No, what's needed here requires considerably more commitment…

Every car brand should have its own olfactory signature: a carefully-crafted defining smell. What is now a random, unintentional by-product of a car's manufacturing process should be brought under rigorous scientific control. It should be subjected to safety-testing, focus-grouping and executive approval at the highest level. In fact, a car's smell should be regarded as the next great marketing opportunity. It should be considered a fundamental selling point for products, print ads and dealerships.

Meanwhile, carmakers are busy removing smell from their cars. While there is no government standard for automotive air quality, the industry is sensitive to their adhesives' effect on workers and customers. (Besides, if you have too many VOC's floating around, the windows fog up.) Carmakers have turned to less toxic, less odiferous glues to hold their products together. The end result: car companies are producing more and more new cars that don't smell like new cars– or anything else for that matter.

Which brings us full circle. Drivers with neutral smelling vehicles feel the need to add scent to their cabins with chemical fragrances. None of these scents are labeled; as "household products" they're not required to list their ingredients. Nor are the "air fresheners" regulated for safety. And they sure don't smell good to a, dare I say it, educated sniffer.

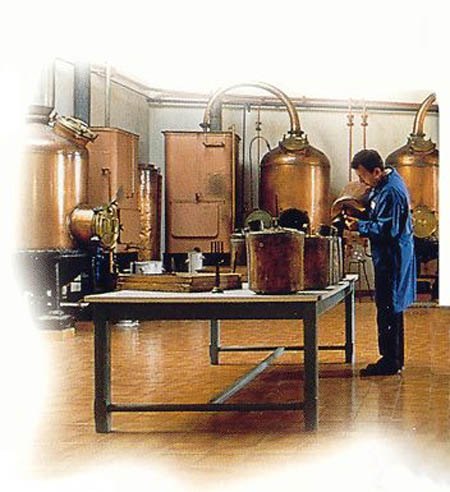

All this could be avoided by the addition of a perfumer to the manufacturing staff. The official "nose" could work with suppliers to add or eliminate smells, or, failing that, infuse the finished cabin with a safe, long-lasting fragrance. Either way, his or her olfactory expertise would help entice new customers and build brand loyalty– as anyone with a nose for business will tell you.

More by Robert Farago

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Varezhka Maybe the volume was not big enough to really matter anyways, but losing a “passenger car” for a mostly “light truck” line-up should help Subaru with their CAFE numbers too.

- Varezhka For this category my car of choice would be the CX-50. But between the two cars listed I’d select the RAV4 over CR-V. I’ve always preferred NA over small turbos and for hybrids THS’ longer history shows in its refinement.

- AZFelix I would suggest a variation on the 'fcuk, marry, kill' game using 'track, buy, lease' with three similar automotive selections.

- Formula m For the gas versions I like the Honda CRV. Haven’t driven the hybrids yet.

- SCE to AUX All that lift makes for an easy rollover of your $70k truck.

Comments

Join the conversation