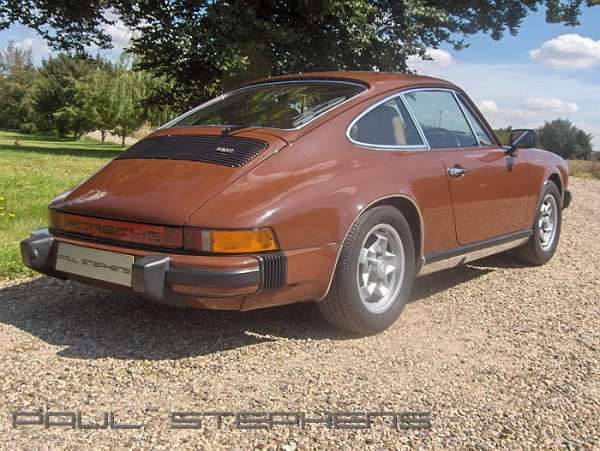

Porsche's Deadly Sin #4: Porsche 911S 2.7

Oops! Under the influence of “Ketel One Citroen” I misnumbered this. Fixed now – jb

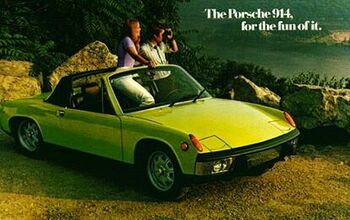

During the Seventies, Porsche was, as Katt Williams might say, in turmoil. Some very strong-willed men were fighting to determine the direction of what was then a very small firm. Ernst Fuhrmann, famous within the company for developing the quad-cam “Carrera” engine that made the 550 Spyder such a giant-killer, was running the show, and he wanted the 911 dead. His arguments were all quite valid: the 911 was not aging well, it was not selling well, and nobody had any idea whatsoever how to make a decade-old car conform to a raft of upcoming safety and emissions regulations.

Some of Porsche’s more paranoid fans believe that Fuhrmann all but sabotaged the 1974 Porsche 911 and its 2.7L engine. The likely truth is far more pathetic. At the time, Porsche’s engineering staff was very small, and they had three major jobs in front of them: developing the all-new 928, seeing the 924 through its teething issues, and uprating the performance of the 911 to meet market needs. Surely the last of these three jobs simply received inadequate attention.

No matter what the reason, when the surprisingly handsome 1974 911 debuted, complete with the mandatory impact bumpers for the US market, it was a complete and utter disaster. Not for the first time, and not for the last, Porsche had built a car that would grenade its engine within 50,000 miles.

This was meant to be a stopgap car, a last hurrah until the 928 could arrive and redefine Porsche as a product and a company. The basic platform was already twelve years old and had undergone just one major revision — a lengthening of the wheelbase and mild suspension re-spec designed to keep the cars from killing their owners in the rain. The original 2.0L six had been expanded to 2.4L in a failed attempt to keep up with cars like the outrageously rapid Jaguar E-Type and fuel-injected Corvette Stingray. Then, as now, Porsche always sold about the slowest sports car any given amount of money could buy, at least when straight-line speed was the measurement.

The 2.4 wasn’t really fast enough, but the impending American emissions standards threatened to slow the 911 down to the point that ordinary Cadillacs would smoke its droopy tail. The solution: to take the 2.7-liter engine developed for the Carrera RS, detune it a bit, and make it standard across the board. As it debuted in 1974, the engine had issues. The magnesium cases warped, the head studs pulled out, and all of this often happened within a few years of purchase. The valve guides didn’t last 50,000 miles, which was a problem that, in some form or another, would dog Porsche until the very last 993 left the factory.

In 1975, Porsche added a “thermal reactor” to meet US emissions standards. At the time, these were only added to US-bound cars; Porsche did not adapt its forward-thinking “world emissions strategy” until much later. The thermal reactor was a horrible, horrible approach to meeting the standards. I don’t know exactly how it works, but to be fair, neither did anybody at Porsche.

When applied to BMWs, the thermal reactor dropped mileage to the teens and cut power to the bone. When added to a Porsche, it did all of the above… but because it was cramped in the back of an air-cooled car, it also accelerated all of the 2.7L’s problems. Hello there, first-year engine failure! Don’t forget that the Porsche warranty of the day was basically one years on defective parts — and neither the dealers nor Porsche were eager to buy new engines for customers. A lot of people ended up with very expensive paperweights. At the time, a new 911 cost about four times as much as an Oldsmobile sedan.

Something had to be done, and that “something” was a move to aluminum engine cases as used in the 930 Turbo. This allowed a bump to 3.0L displacement. The resulting car was the 911 Super Carrera, or “911SC”, which debuted in 1978. That car had a whole different set of mechanical issues, one of which — defective chain tensioners — could also cause a complete engine failure, but it was far more reliable than the guaranteed-to-melt 2.7L.

If you see a 911 2.7 on the road today, chances are it’s been all squared away, either through a variety of innovative fixes or the simple installation of a 3.0. Many of these cars now provide very useful service to their owners. At the time, however, they turned a lot of people away from Porsche permanently. Porsche Cars North America’s arrogant attitude, something that continues to the present day, didn’t help matters.

I wish I could come up with a legitimate reason for Porsche’s decision to leave the 2.7L in production for three full years after they first saw problems, but if anything that represents fast service by Porsche standards. The water-cooled grenade stayed in service for eleven years, you know.

Not that anybody in Stuttgart was all that concerned about the 911’s downward spiral. It was an old car and anybody stupid enough not to wait for the far-superior 928 got what they deserved. Fuhrmann expected that 911 production would terminate some time in the early Eighties, possibly as early as 1980.

Nobody could predict that the 928 would turn out to be an expensive, troublesome boondoggle and that the air-cooled 911, far from being killed around its eighteenth birthday, would in fact go on to live a full thirty-six years in production. In that second lifetime, 911 owners would learn about a whole new range of maladies, and they would also learn that some things never change. Porsche didn’t really care then about long-term customer satisfaction, and they don’t really care now. Still, if you can get behind the wheel of a ’75 911S and hear that magic “whoooooooOOOOOOOOP” as the mill catapults you squarely out of your late apex, perhaps you won’t care about that, either.

More by Jack Baruth

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- MrIcky 2014 Challenger- 97k miles, on 4th set of regular tires and 2nd set of winter tires. 7qts of synthetic every 5k miles. Diff and manual transmission fluid every 30k. aFe dry filter cone wastefully changed yearly but it feels good. umm. cabin filters every so often? Still has original battery. At 100k, it's tune up time, coolant, and I'll have them change the belts and radiator hoses. I have no idea what that totals up to. Doesn't feel excessive.2022 Jeep Gladiator - 15k miles. No maintenance costs yet, going in for my 3rd oil change in next week or so. All my other costs have been optional, so not really maintenance

- Jalop1991 I always thought the Vinfast name was strange; it should be a used car search site or something.

- Theflyersfan Here's the link to the VinFast release: https://vingroup.net/en/news/detail/3080/vinfast-officially-signs-agreements-with-12-new-dealers-in-the-usI was looking to see where they are setting up in Kentucky...Bowling Green? Interesting... Surprised it wasn't Louisville or Northern Kentucky. When Tesla opened up the Louisville dealer around 2019 (I believe), sales here exploded and they popped up in a lot of neighborhoods. People had to go to Indy or Cincinnati/Blue Ash to get one. If they manage to salvage their reputation after that quality disaster-filled intro a few months back, they might have a chance. But are people going to be willing to spend over $45,000 for an unknown Vietnamese brand with a puny dealer/service network? And their press photo - oh look, more white generic looking CUVs. Good luck guys. Your launch is going to have to be Lexus in 1989/1990 perfect. Otherwise, let me Google "History of Yugo in the United States" as a reference point.

- Schen72 2022 Toyota Sienna, 25k miles[list][*]new 12V battery, covered by warranty[/*][*]new tires @ 24k miles[/*][*]oil change every 10k miles[/*][*]tire rotation every 5k miles[/*][/list]2022 Tesla Model Y, 16k miles[list][*]nothing, still on original tires[/*][/list]

- Kjhkjlhkjhkljh kljhjkhjklhkjh Elon hates bad press (hence TWITTER circus) So the press jumping up and down screaming ''musk fails cheap EV'' is likely ego-driving this response as per normal ..not to side with tesla or musk but canceling the 25k EV was a good move, selling a EV for barely above cost is a terrible idea in a market where it seems EV saturation is hitting peak

Comments

Join the conversation

Think of the thermal reactor as a catalytic converter without a catalyst. The idea was to burn up any unburned hydrocarbons coming out of the engine. The first Mazda rotaries (RX-2, RX-3) had one (1972). In order for the reactor to work correctly, the engine had to be run very rich (with the expected adverse effects on fuel economy) to provide a sufficiently fuel-rich exhaust, and the converter needed to be located as close as possible to the exhaust manifold in order to have the exhaust hot enough to light off. With the Mazda, whenever you shut the engine down, you could hear the reactor clicking and cracking as it cooled down. (I owned one.) Jack is certainly correct; this is not something you want to hang on an aircooled engine.

Since the old man let his punk kid put the engine where it should never be, the 911 has been a mortal sin. The Swiss (or maybe the Danes, I forget) required weights in the nose of the 911 to try to make it sorta safe to drive - by the incredibly loose metric of the day. The 911 is still an embarrassment all these years later. Turn HAL off in a new TT and even Schumacher would stuff that POS in a week. A Panamera TT is a "real" Porsche.