No Fixed Abode: No Matter How Far Wrong You've Gone, You Can Always Turn Around

I was still in my 20s, browsing my local library’s jazz catalog with what I hoped was an open mind, when I found Brian Jackson and Gil Scott-Heron’s “Winter In America” tucked between Wynton Marsalis and Chick Corea. I had a vague idea of who Scott-Heron was from my years in school, so I snagged it, put the CD in my Fox on the way home, and I was … struck dumb. This was something new for me, both musically and politically. In the years since, I’ve often thought that if God truly loved me he would have given me Gil Scott-Heron’s steady baritone instead of my over-modulated tenor.

In the years that followed, I persevered as a fan of Scott-Heron through the man’s ups and downs. Shortly before his death, he stunned me and everybody else again with I’m New Here, a heartfelt but judiciously studied effort that was aimed with laser precision at rap fans and the regular-at-Yoshi’s crowd alike. In that album’s title track, Scott-Heron gathers up what is left of his voice and growls, “No matter how far wrong you’ve gone / you can always turn around.” It was a knowingly ironic statement from a man who could clearly foresee his imminent death from AIDS-related complications, but it was also a final benediction, a last bit of weary advice from a man who had long viewed himself as a prophet without honor in his own community.

That phrase — “No matter how far wrong you’ve gone / you can always turn around” — has weighed heavily on me lately, for any number of reasons. I have a few friends, some more dear to me than others, who would benefit mightily from a serious application of that advice. But since this is at least nominally a blog about cars, let’s talk about what it means to our four-wheeled decisions, instead of how it might apply to relationships that should have been dropped in the Marianas Trench years ago.

Yes, let’s do that.

The first Google result, and the most frequently cited paper that I can find, for the idea of “sunk cost” can be found at ScienceDirect. You’ll need to pay money if you want to read the whole thing, but let’s face it: we live in an era where “Science” is to our chattering classes what “God” was to their grandparents, which is to say that “Science” is something to be invoked at every public opportunity while being simultaneously held at arm’s length whenever possible.

I hear a lot about what “Science tells us” from people who didn’t make it through high school chemistry class, and I read a lot of complaints about “Science deniers” from people who couldn’t describe the scientific method for a million dollars in hard currency. A while ago, there was a massive collective giggle from the Internet about a pair of overweight rappers who wondered exactly how magnets work. I made it my personal mission in life for about 90 days to subject anybody who made a dismissive comment about said rappers to some intense questioning regarding the precise nature and mechanics of electro-magnetism. None of my interviewees ever made it as far as the so-called strong and weak force, to my immense and predictable delight.

The typical reader, therefore, will be satisfied if we just read the abstract. Nah. Still too much hassle. Let’s just pick out the important parts. I’ll do it for you:

The sunk cost effect is manifested in a greater tendency to continue an endeavor once an investment in money, effort, or time has been made … It is found that those who had incurred a sunk cost inflated their estimate of how likely a project was to succeed compared to the estimates of the same project by those who had not incurred a sunk cost … people will throw good money after bad … The sunk cost effect was not lessened by having taken prior courses in economics.

You can see this effect all around you. At the blackjack table, where people who have lost a lot of money can’t just walk away and cut those losses. In our universities, where people double down on a losing major like history or social science or pretty much anything that isn’t finance or STEM in the vain hope that having a doctorate in feminist movie theory will be somehow more remunerative than merely having a master’s degree in the subject. In the woman who keeps some low-achievement fedora-wearing dog trainer around because she’s already put so much effort into their relationship and she doesn’t want to admit that it’s all been wasted time.

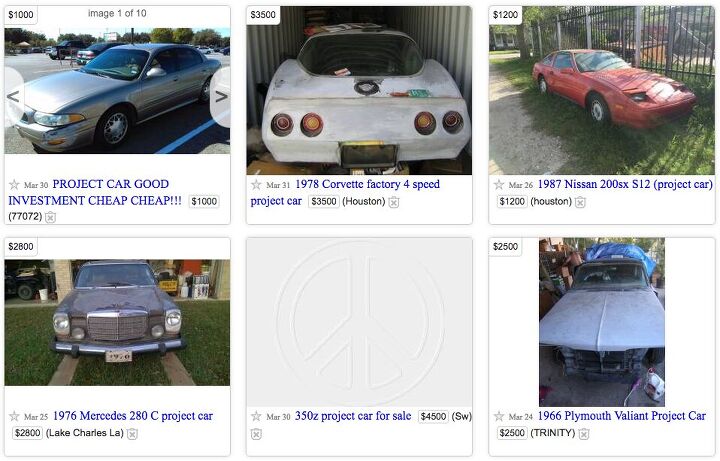

All of these are great examples, even if at least one of them seems oddly specific and two of them definitely would if you had a chance to follow my brother around a casino, but you simply cannot beat automobile owners when it comes to following a sunk cost right into the proverbial ground. In fact, you can argue cars are the number-one examples of sunk cost psychology in the world.

After all, we live in a world where most tangible items are either highly durable — homes, airplanes, shovels, proper dress shoes — or absolutely disposable — electronics, sweatshop clothing, nearly everything made in China. Items in the first category are relatively unlikely to inspire terrible sunk-cost decisions, because you’ll get your value back if you wait long enough. Very few homes are torn down because they are truly beyond repair. Items in the second category don’t inspire any particular efforts at preservation. Does anybody in this country, even the most desperately poor, sew patches on clothing any more? Does anybody try to repair an iPod Touch?

By contrast, nearly every automobile experiences a brief final phase of life where somebody puts too much money and effort into it. Long-time readers will remember the work of Crabspirits, the fellow whose trenchant quasi-fictional observations on the last functioning moments of junked cars were both hilarious and heartbreaking. Many of us recognized friends, relatives, or our own actions in those tales.

In a perfect world, every owner of a vehicle in its twilight years would use a simple formula to determine if a repair was worth doing. It would be something like: cost of repair divided by expected additional months of usage, compared to the cost of obtaining replacement vehicle that does not need repair. The problem with that sensible approach is:

a) the kind of people who would engage in careful equation-pondering are precisely the kind of people who only rarely find themselves in those sorts of desperate straits;

b) the kind of people who find themselves in those sorts of desperate straits rarely possess the intellectual and educational tools to make those determinations;

c) it’s extremely difficult to come up with reliable numbers for any of the above variables.

I think ol’ letter C is responsible for a lot of misery in these situations. The mechanic comes out front, wiping his hands, and tells you that while they were fixing insert name of completely incomprehensible item here they found a problem with insert different, but equally foreign, part or assembly of parts. Or they have no trouble fixing it but the new part doesn’t last as long as you’d hoped. Or something else goes wrong shortly afterwards. Or the $2,000 car your brother-in-law said he would hold onto for you gets sold due to a misunderstanding. It’s very easy for members of the upper-middle class to cluck and criticize when the working poor can’t figure out how to make $500 decisions, but many of these same people found themselves deep underwater on their McMansions nine years ago and they treated it like an act of God that deserved immediate federal intervention.

Of course, none of the above discussion provides an adequate explanation for your crazy uncle who has put five transmissions into his Chrysler minivan, or the guy in the office down the hall who bought an old W220 S-Class, instantly experienced an Airmatic failure, and did anything besides selling the car for scrap. Some people really should know better, and they can afford to know better, but they refuse to know better.

I used to see this sort of thing in Volvos and Saabs that were traded in at my Ford dealership way back in the day. These very tidy professorial types would arrive. Sometimes they would actually be professors. Sometimes they would be professors of business or economics. They would arrive with thumb-thick binders of cost-no-object repairs done with brand-new factory parts to 15-year-old shitboxes with seats worn through to the springs. You would go through the binder and do the numbers for fun; the average monthly cost of repair would have put them in a new Explorer years before they decided to give up.

Rarely was the last bill or estimate (they always brought the estimates, these cautious and purposefully ethical folks) larger than or more complex than the ones that preceded. In fact, it was often the reverse. They’d swap in a new transmission then call it quits over a power steering pump. They would have the engine rebuilt with a factory long block and then give up because the dashboard lights didn’t come on for the evening trips that rarely ranged outside their own neighborhood.

Mark my words, however, the folks who wrote the above research paper were dead-right about one particular thing. The more money that Professor Smith wasted on his ’83 Saab 900, the more money he’d throw in the pit after it. Rarely did the cars come in with five repairs in five years. Either they’d have one major problem that resulted in the trade-in, or they’d have the thumb-thick binder. Good money after bad, again and again. Each repair promised to be the one. After this repair, they would surely get another trouble-free year out of an ancient Eurocar that was never designed to survive a five salt-soaked winters, let alone a dozen. Each promise was a lie.

As the owner of a watercooled Porsche that is just a couple seasons away from a 15th birthday, I’m starting to think about how and why I might sell it. Truth be told, my Boxster S has been inexpensive and almost trouble-free to run — by German-car standards, mind you. If a Civic cost this much to run, you’d bury it in the hole they used for all the E.T. cartridges. It’s fundamentally worthless; I doubt I could get fifteen grand for it. There’s a subterranean floor to its minimal value, roughly defined as “base for a Spec Boxster build,” that will stay steady for a very long time.

Therefore, any year where it doesn’t cost me much money would be a good year to keep it. And any year where it costs me a lot of money is a good year to sell it. As long as I adhere to that, I’ll be fine. My concern is that I’ll have a light rainfall of two-thousand-dollar problems. Control arms. Catalytic converters. Dashboard flickering. And each one of those will feel like it could be the last … but it won’t be.

All I can say in my defense is that I didn’t let my 944 bleed me out like that. I bought it as a no-stories, no-excuses car for $6,000. I put $5,000 into it. It was a $6,000 car. Five years of occasional use later, it was a $4,000 car that needed $8,000 of work to be right. At which point it would have been a $6,000 car. When the clutch slave followed the clutch master into the big parts bin in the sky, I did all the numbers. Then I sold it for a few grand to somebody who wanted a project. It broke my heart to see the car go, but the math of it was incontrovertible.

If I can do it with my beloved 944, everybody else should be able to make the same decision with their old Saab — or even their old Camry. Let’s go back to Gil Scott-Heron for a final comment: “It may be crazy / but I’m the closest thing I have / To a voice of reason.” That’s true for all of us. No matter how far wrong you’ve gone, you can always turn around. But here’s something I’ve learned at my own cost: the decision to turn has to come from within.

More by Jack Baruth

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Buickman I like it!

- JMII Hyundai Santa Cruz, which doesn't do "truck" things as well as the Maverick does.How so? I see this repeated often with no reference to exactly what it does better.As a Santa Cruz owner the only things the Mav does better is price on lower trims and fuel economy with the hybrid. The Mav's bed is a bit bigger but only when the SC has the roll-top bed cover, without this they are the same size. The Mav has an off road package and a towing package the SC lacks but these are just some parts differences. And even with the tow package the Hyundai is rated to tow 1,000lbs more then the Ford. The SC now has XRT trim that beefs up the looks if your into the off-roader vibe. As both vehicles are soft-roaders neither are rock crawling just because of some extra bits Ford tacked on.I'm still loving my SC (at 9k in mileage). I don't see any advantages to the Ford when you are looking at the medium to top end trims of both vehicles. If you want to save money and gas then the Ford becomes the right choice. You will get a cheaper interior but many are fine with this, especially if don't like the all touch controls on the SC. However this has been changed in the '25 models in which buttons and knobs have returned.

- Analoggrotto I'd feel proper silly staring at an LCD pretending to be real gauges.

- Gray gm should hang their wimpy logo on a strip mall next to Saul Goodman's office.

- 1995 SC No

Comments

Join the conversation

Not a correction, just wanted to let you know that I'm New Here is a cover of a song by Smog aka Bill Callahan on a phenomenal album called A River Ain't Too Much to Love. Also, I'll continue putting my money into my Roadmaster until Earth figures out how to make a superior automobile

Guilty as F'n charged, Jack. This was brilliant. I have an empty space in my garage and a binder full of Porsche 911 repairs to prove it.