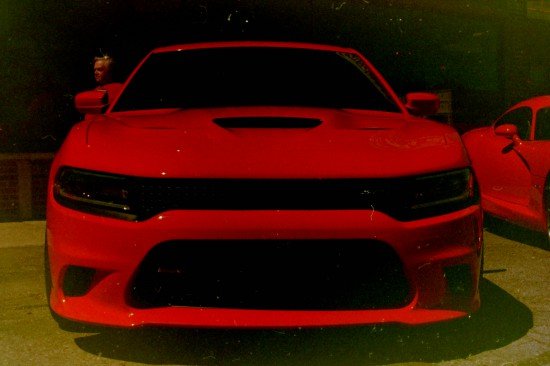

Worth The Wait? Old School Coverage Of Dodge's Newest Hellcat

Let’s start this off with a caveat. I make no pretensions to being a photographer. At best I can compose and frame a decent snapshot. Years ago I realized that if I wanted to get more serious about photography I’d have to start learning a bunch of technical things like depth of field and f-stops and I already had enough hobbies. As a result, I have a great deal of respect for professional and serious amateur photographers and cinematographers. That respect has grown since I started writing about cars, as that gig often requires taking photographs to accompany my words.

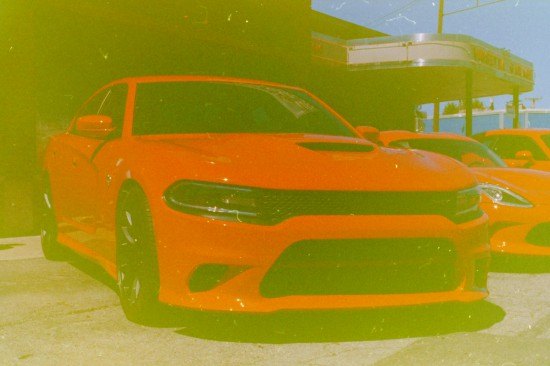

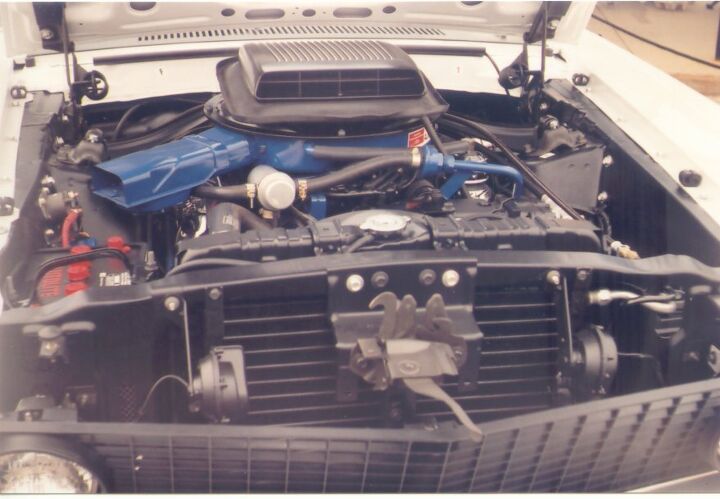

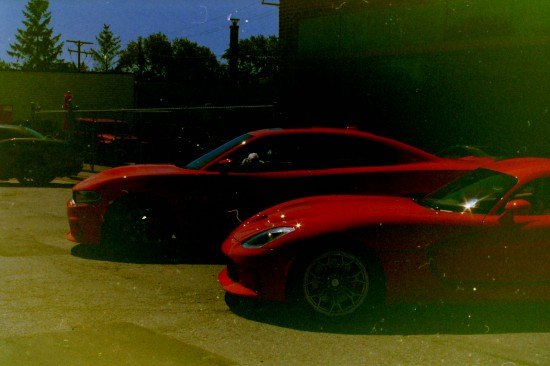

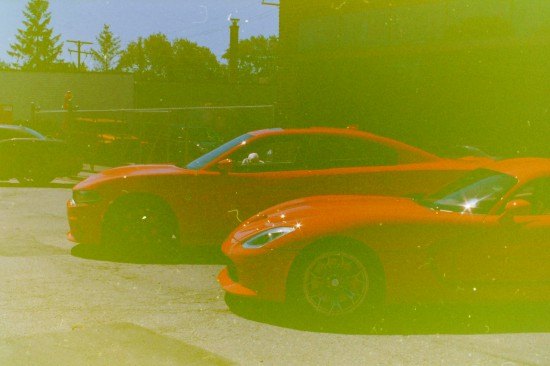

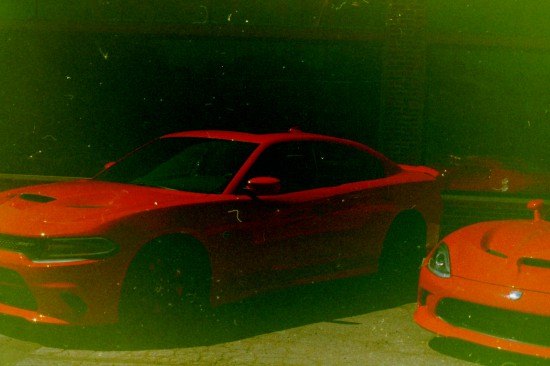

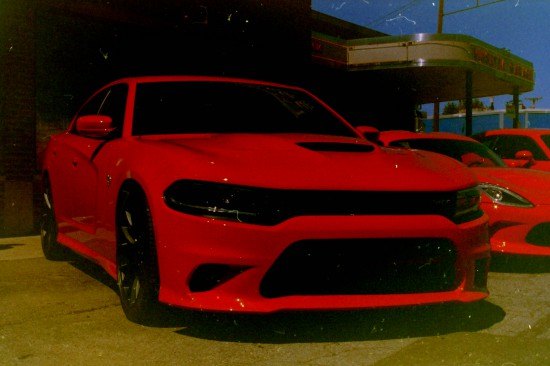

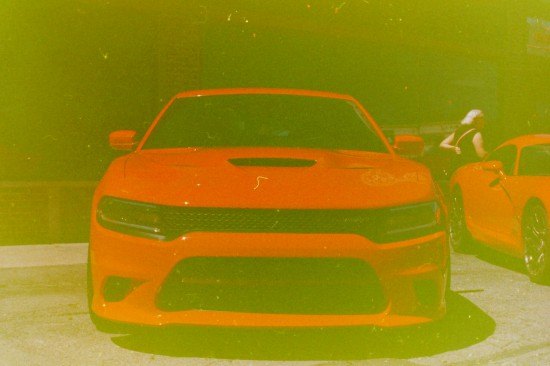

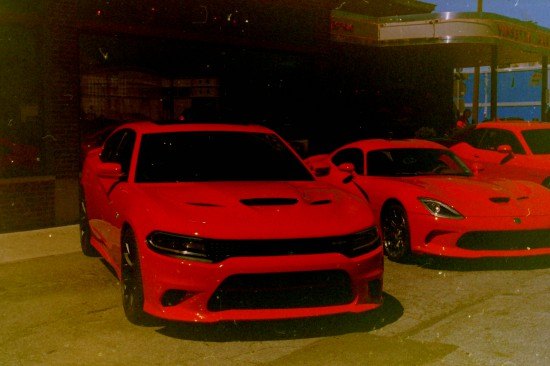

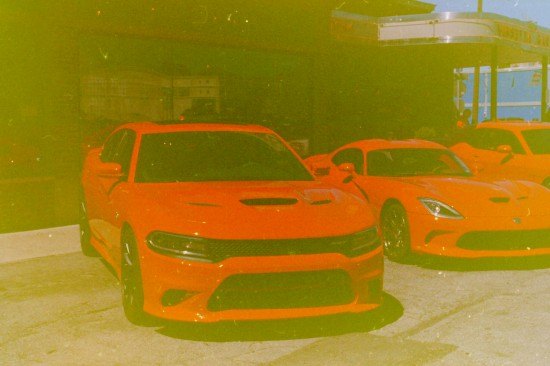

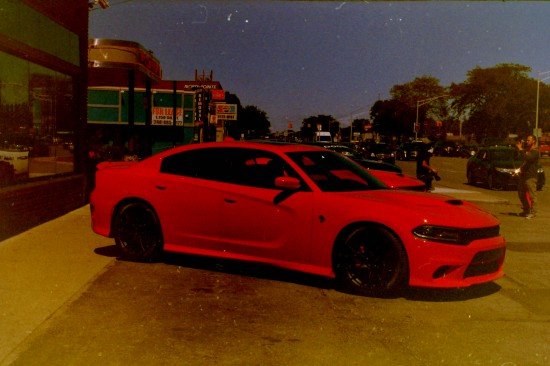

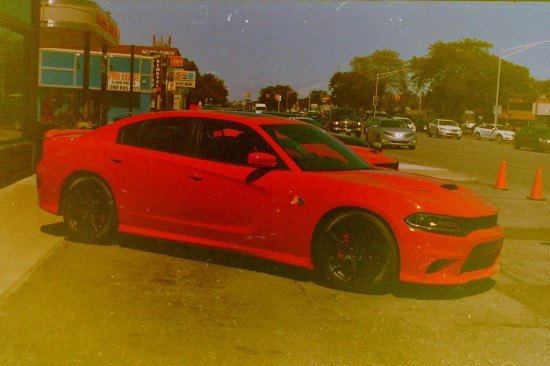

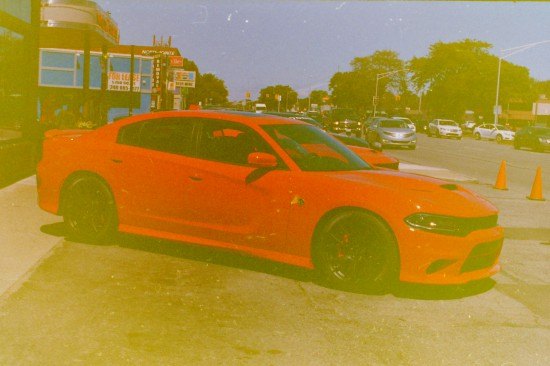

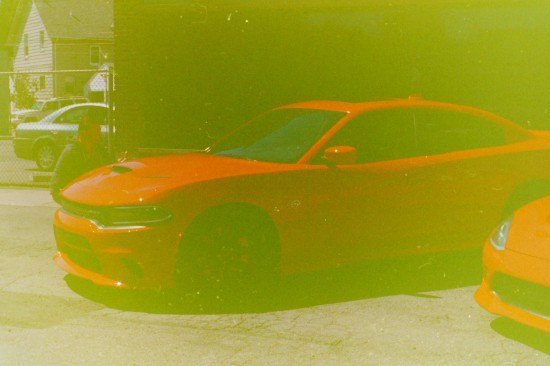

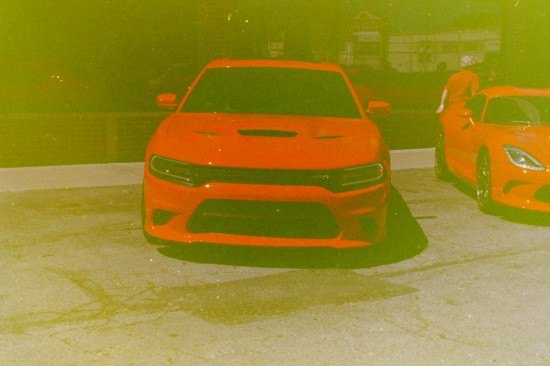

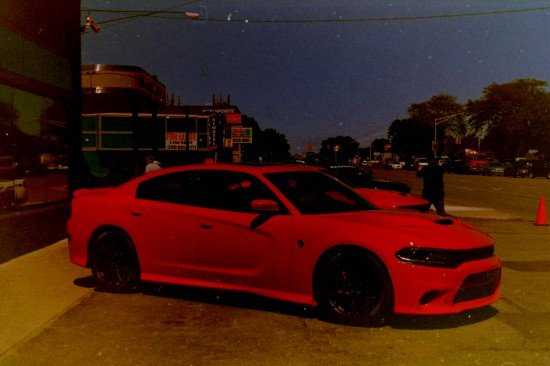

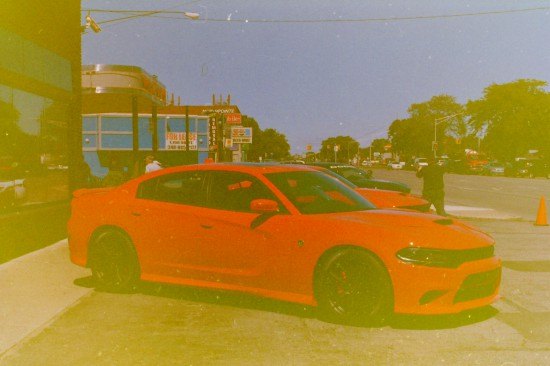

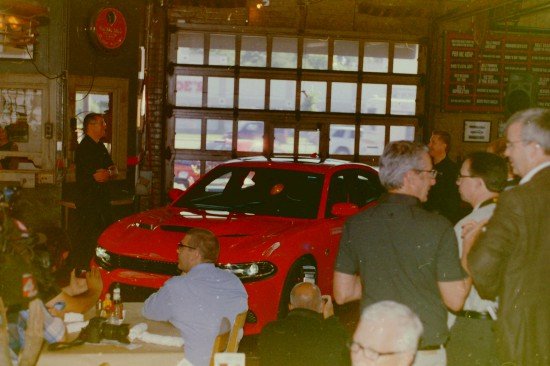

Last Wednesday, Derek Kreindler and I worked together to make sure that The Truth About Cars had someone to cover the Dodge Charger Hellcat reveal on-site at the event, which wrapped up around noon. We managed to get almost 100 high definition color photographs of the event and the car picked out, cropped and up on this site by mid-afternoon. We also decided that the reveal, and subsequent Woodward Dream Cruise, would be a great opportunity to show you how long you would have had to wait to see color photos of an event back in the pre-digital era.

We live in an age of miracles and wonders. At the celebration of my Bar Mitzvah I received actual paper telegrams via Western Union. Nowadays, I can be walking down the street in suburban Detroit and my brother, who lives in Jerusalem, Israel, can send me a photograph on my phone and then call me about it, and because of flat rate cellphone service, neither one of us is actually paying very much for that communication. Far less, I’m sure, in both real or inflated dollars, than those telegrams cost my parents’ friends and relatives in 1967. Come to think of it, my brother taking and sending me that photo via SMS was also a lot cheaper than it used to cost to take and process a photograph and mail it to someone halfway around the world.

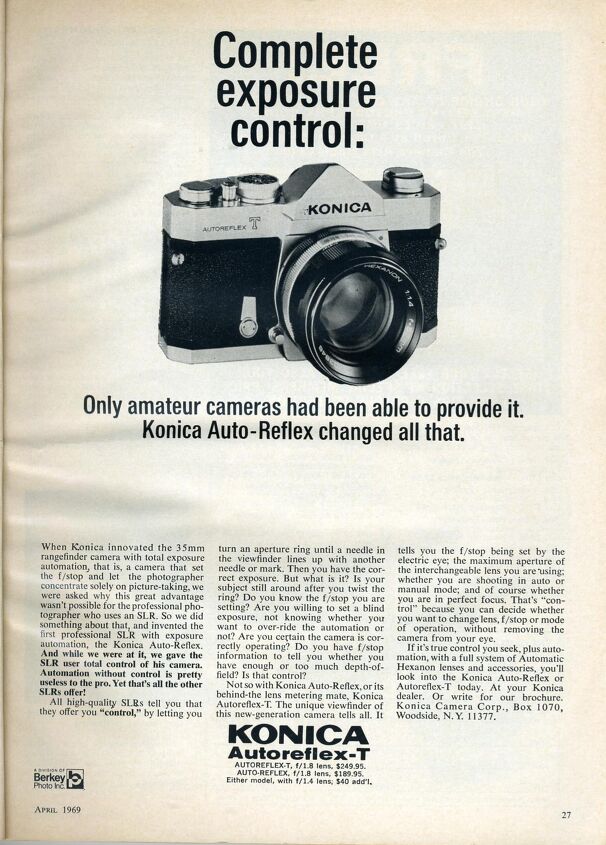

My mom, I’m also sure, has those telegrams somewhere in her house. As the saying goes, may she live to 120. Three quarters of the way there, though, she’s showing some signs of age and recently moved into a nice apartment at a senior assisted living facility. My sisters also live out of town so it’s up to me to go through mom’s house. My late father started taking photographs, color slides and home movies before I was born. He had three 8mm movie cameras that I’ve found while cleaning and since there are a couple of rolls of 16mm movies in the box of home movies, he must have at least had access to a 16mm movie camera way back when. As far as still photography was concerned, the camera of my father’s with which I’m most familiar is his Konica Autoreflex T2 35mm single lens reflex he bought when I was in high school. He had another Konica before that but when the T2 came out he traded up.

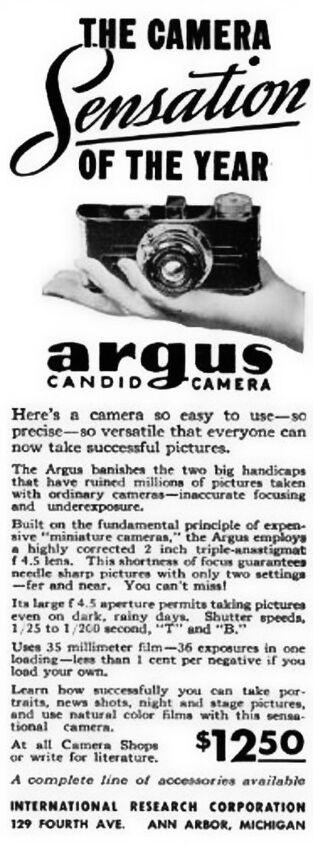

That’s the camera that I personally used taking photos of my family as my own kids grew, the camera that I took on vacations and camping trips to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. However, before the Konicas, and before a series of Polaroids going back to the black and white days when you had to wipe the “finished” print with a pad soaked with fixer, my dad had an Argus C3.

Argus was a company in Ann Arbor, Michigan that can be said to have popularized the 35mm photographic format in America. Charles A. Verschoor had a company that produced radio receivers, International Radio Corporation. On a trip to Europe he noticed the costly Leica cameras being made to use Kodak’s then new daylight loading 35mm film cartridges and resolved to make a similar camera, but one that could be affordable, costing just $10. Starting in 1936 with the Model A, Argus would go on to sell millions of cameras over the next three decades. Argus cameras were so popular that they even affected how people talk. The title of Alan Funt’s Candid Camera television show was taken from a phrase popularized by Argus.

With the success of the Model A camera, the company was renamed Argus, after the mythological creature with 1,000 eyes. The cameras were almost entirely made in Ann Arbor, where the company was a major employer. Even the lenses, which were said to rival Leica’s lenses in optical if not manufacturing quality, were made in-house. The Argus C3, affectionately called “The Brick” by collectors, sold over 3 million units in the 1950s and 1960s. However, like the Michigan based car companies a decade later, as it entered the 1960s Argus didn’t recognize what a competitive threat Japanese companies could be and today the only thing left of Argus in Ann Arbor is a museum devoted to the company and its role in American culture.

I checked out the mechanical functions on my father’s C3. The aperture opened and closed, the shutter worked and so did the shutter timing mechanism, it seemed. I did have to clean accumulated dust from the lens, viewfinder and rangefinder. What’s a rangefinder? Before digital let everyone see what the main lens was seeing via sensors and viewscreens, there were SLRs. That stands for single lens reflex. Photography buffs can correct me if I’m wrong, but the “single lens” part is in contradistinction to older twin lens reflex (TLR) cameras that had one lens for the shutter/film and another for the photographer’s viewfinder. The two lenses worked in tandem so the photographer would know when things were in focus. SLRs’ viewfinders were able to see through the main lens via an internal mirror setup that retracts just before the shutter opens.

Before SLRs became popular professional photographers, the kinds who would be covering something like the introduction of a new car, as well as serious photography enthusiasts, would be using a TLR. Members of the general public were more likely to be using simple fixed focus viewfinder cameras. Photography buffs on a budget, though, had the option of a rangefinder camera. Rangefinder cameras had lenses that could be focused based on distance to the subject. There are two optical ports in the back of a rangefinder camera, one to frame the shot, and the other to determine distance to the subject. The rangefinder port gives a split image from the viewfinder and from the rangefinder. Since there is a parallax between the two image sources, when the two are lined up, that will correspond to the right distance. The knob that adjusts the rangefinder is ganged via a gear to the lens focusing ring. Alternatively, you can just set the distance using a scale on the knob.

To shoot with a rangefinder camera, you first have to frame the shot with the main viewfinder, then check the focus with the rangefinder, then go back to the main view to take the photo. Of course, since just about everything else on the Argus C3 is manually set, that’s just the last step, almost, in the process of taking a photo.

First you have to set the aperture, how large the shutter opening will be, and the shutter speed, based on some kind of chart that references those two settings relative to the ASA speed of the film (how sensitive to light it is) that you are using. Ah, but don’t think you’re ready to shoot just because you’ve set the camera. First you have to cock the shutter mechanism with a small lever on the front of the camera. Then you have to make sure that you move your fingers out of the way because if you don’t, the lever will hit your finger when the shutter releases, causing motion blur in your photo, as you can see in the first roll that I shot with the Argus at the Charger reveal.

Once you’re done taking the photo, you have to advance the film by winding it, but first you have to press on a little film release button for the first 1/4 turn, then wind to the next shot. If you hold the button down too long, you skip past a frame and waste a shot on the roll. If you forget to advance the film, there is nothing to prevent you from double exposing (or triple exposing for the matter) a frame. Some of you may never have seen a double exposure before. I know you can use a photo editor to reproduce the look from two separate shots but is it even possible to natively shoot a double exposure with a digital camera?

My dad’s Argus was made in 1957. I believe that the Konica T2 came out in 1971. The Autoreflex from Konica was the first “through the lens” metering SLR and it can shoot in full automatic mode. Well, full automatic mode circa 1971. You just set the film speed and the shutter speed and the camera will auto-expose and set the aperture itself. There’s a handy light meter inside the viewfinder that lets you know when you’re out of range, or how changing the shutter speed will affect the aperture. It also has mechanisms that prevent double exposures and missed shots. The film won’t advance unless you’ve triggered the shutter and once you’ve triggered it, it won’t release again without advancing the film.

When I took the cameras to the Charger Hellcat reveal, I had to use the Konica in full manual mode because the batteries were dead and you have to go to a camera shop to get the air-zinc batteries from Wein that replace the old stable-voltage mercury batteries that were specified when the camera was made. Still, even in full manual mode the Konica was much easier to use and not just because of its simpler focusing.

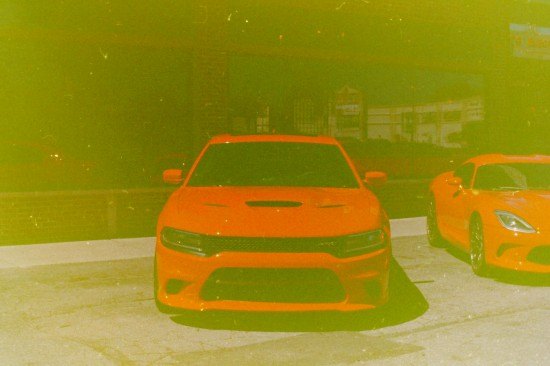

Since I was playing around with a camera that was already 10 years old at the time of my Bar Mitzvah (the serial # indicates it was made in 1957) I didn’t want to throw money at the idea. Before I spent money on film, I decided to try out both cameras with some unexposed (but out of date) Kodak Gold film in an ASA speed of 200 I’d found in the house. Checking with film photography sites online (it’s had a bit of a revival in part because hipsters have embraced film) I found that if it isn’t frozen (which preserves film for a long, long time) old film will be slower, i.e. less sensitive to light, the colors might be off and the results might be grainy, but you’ll likely still get some kind of image on the film.

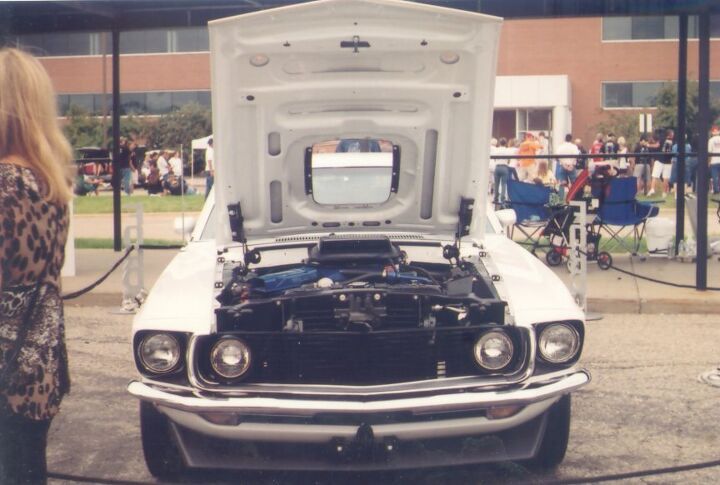

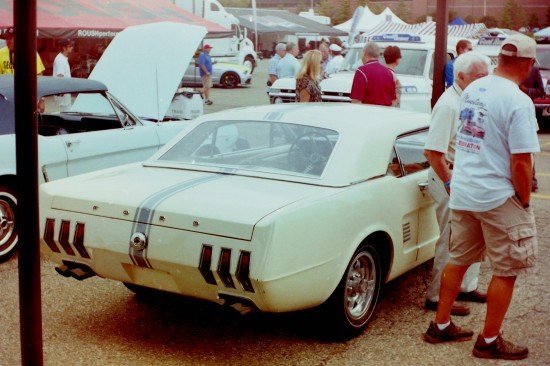

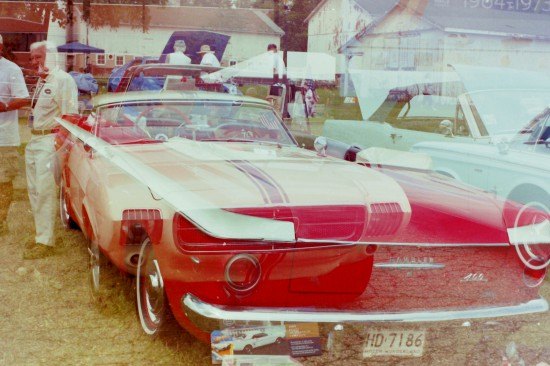

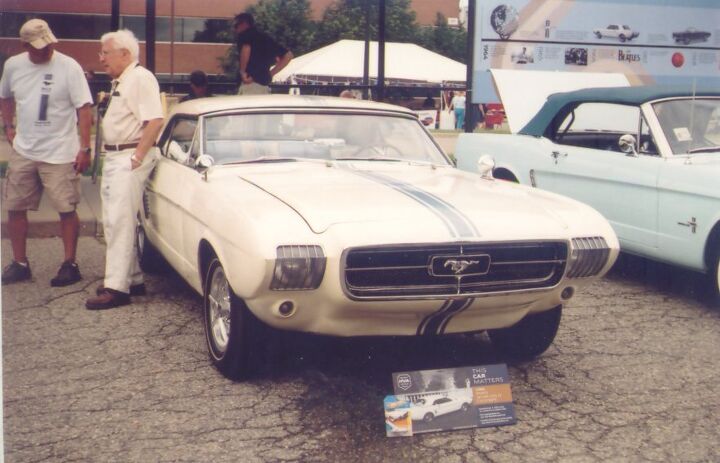

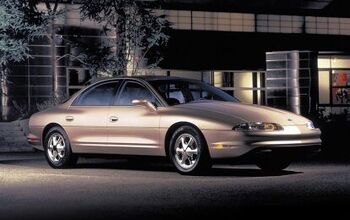

With that in mind, along with what rudimentary photography skills that I have, and my dad’s old pocket Kodak photography guide to help with the settings, I used the two film cameras at the Hellcat event. I also used them at some Woodward Dream Cruise events as well as at the regional annual American Motors club meet in Livonia and the huge Mustang Memories show held at Ford headquarters. The idea was to show just how long you would have had to wait to see color photos of a car event back then.

While I could have taken the film to a chain drugstore with one-hour photo processing, that seemed a bit anachronistic since when both of those cameras were new, there was no one-hour film processing, at least with color film, and not at all for consumers. They didn’t have film processing machines in drugstores then, you had to send the film off for processing at an out of town lab. Photographers shooting news would likely have access to a darkroom, either their own or one belonging to their employer, but they would have been shooting black and white. Color, at least as far as the news industry was concerned, was reserved for monthly publications (it’s worth pointing out that daily newspapers didn’t print in color until the 1980s). Autoweek might have had a color photograph on the cover, but inside it was mostly black and white.

It usually took at least a week, sometimes two, to get your color negatives and prints back.

We’ve gained speed, but we’ve lost the anticipation that came with traditional chemical photography. Did they come out? Which ones came out? Which ones could have been better? Which shots had our thumbs over the lens?

Film back then was also expensive. You paid for the film and processing no matter if you got any usable shots or not. The fact that a family spent money on photography meant that getting a permanent record of their memories was important. It wasn’t cheap to do so. I remember my dad looking for combination film/processing deals and buying bulk 35mm movie film loaded into cartridges. Speaking of movies, movie film was even more expensive and could be an even bigger pain to use. I found an unexposed “double roll” of 8mm Kodachrome II movie film. The double part meant that it was 16mm stock, you’d shoot half (after having to load spooled film in dim light so you didn’t expose it and fog the film), then have to flip around the spools so you could shoot the other half. After developing, the processor would slit the film down the middle into two 8mm strips and then splice them end to end.

Since I wasn’t sure the film would process and develop, I figured that it made more sense to have it done at a camera shop with their own processing lab than to trust a technician working for a contractor to Rite Aid or CVS. Woodward Camera had graciously sold me some batteries for the Konica when they were actually closed for the Dream Cruise and hosting a Daughters of the American Revolution event. Since they were nice to me, I took the film to be processed there. By the way, if you happen to shoot film, before having it done at a drugstore, check your local camera shop. Woodward Camera was actually about 20% cheaper than Rite Aid. They also processed the film in less than a day. As a result, you’re seeing the photos now instead of next week.

I also wanted to use my dad’s old Revere 8mm movie camera. It’s got a turret with a couple of lenses and it’s build like a fine watch. More important, since I’m writing what is essentially a piece about old cameras for a car site, Revere started out in the automotive business, making radiators. That little movie camera is a jewel. It will work mechanically long after we’re all dead. However, it takes a film magazine and there weren’t any unexposed 8mm magazines that I could find in mom’s house. I ended up using dad’s Kodak Brownie movie camera, whose build quality showed what a mass-market consumer item it was compared to the Revere. Still, it seemed to function okay.

Later on there were battery operated movie cameras but when “home movies” were really big, you had to wind up a spring for the clockwork mechanism. Since the mechanism is similar to how a movie projector works, an old home movie camera makes the same sorts of noises. They’re hard not to notice. While shooting movies at the Charger reveal, a young man asked me, “Are you shooting tape?”. Tape??!!

I’d show you the “video” results but after I shot it I found out that nobody does Kodachrome II movie film processing anymore, at least not in color.

While the old age of the film that I shot at the Charger Hellcat reveal made the results unacceptable for publication if I wasn’t trying to make a point, most of the prints still came out, more or less, but the differences in results clearly showed how much easier the Konica was to use. Out of 24 exposures, the Konica produced 22 shots that would have been usable with new film. Out of 12 exposures with the Argus, only one came without motion blur, double exposures, or just a blank frame because I advanced the film without taking a shot. Everything that could have gone wrong did, another reason why I like digital photography.

I hadn’t really planned on doing more than shooting those two rolls of old film but when I was checking out processing prices, I noticed that Rite Aid was selling four packs of their house brand 35mm film in ASA 400 for $14.99 and there was a buy one get one free deal for loyal customers, of which I am one. That works out to less than $2/roll. It said it was made in Japan and with so few companies making film these days, that almost certainly means that it’s made for Rite Aid by Fuji.

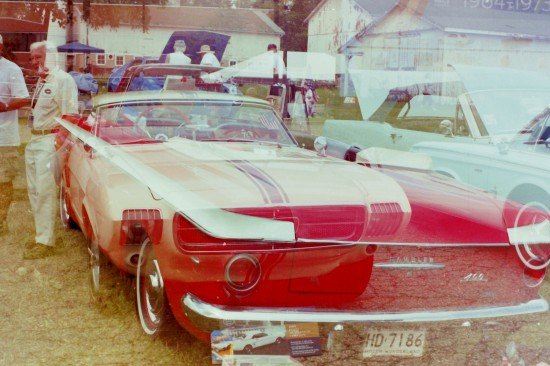

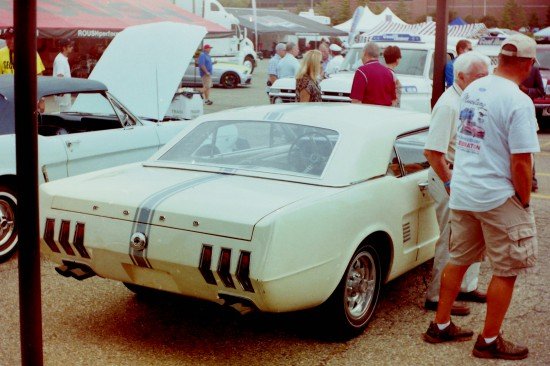

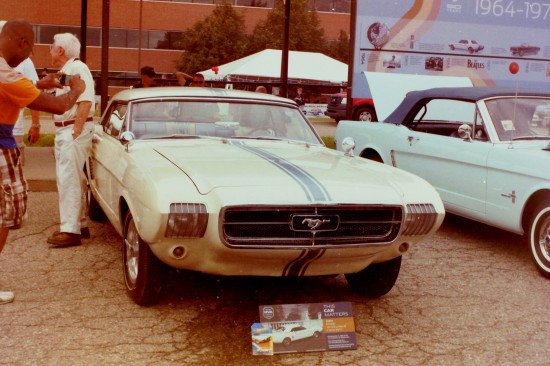

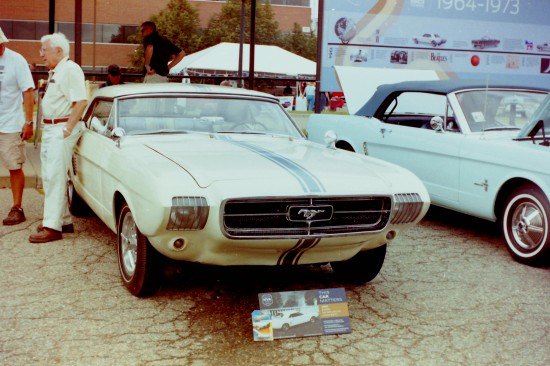

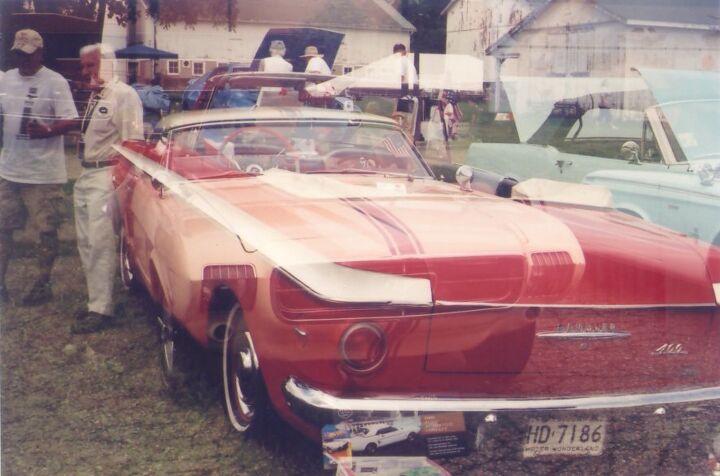

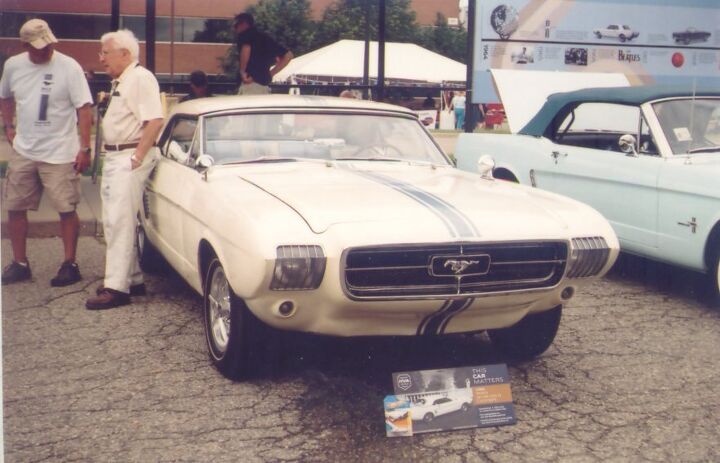

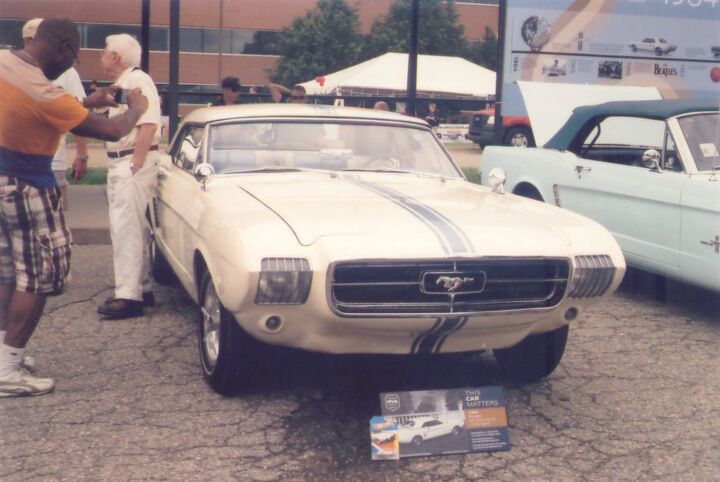

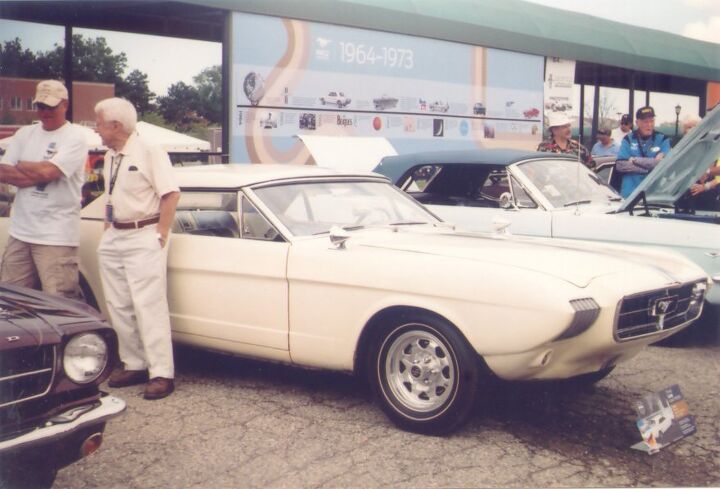

Though I still managed to double expose a shot with both a Dodge Power Wagon and vintage Fiat 500s at the Dodge display on Woodward, by then I knew to keep my finger out of the way of the cocking lever when it springs back into position. The rest of the new film shot on the Argus at the AMC and Mustang shows came out fine.

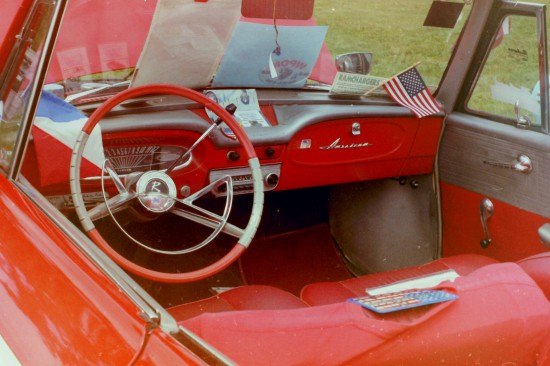

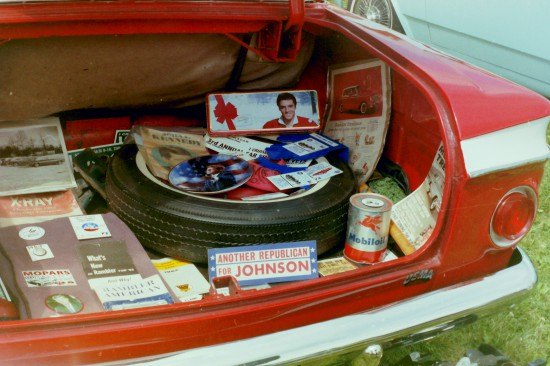

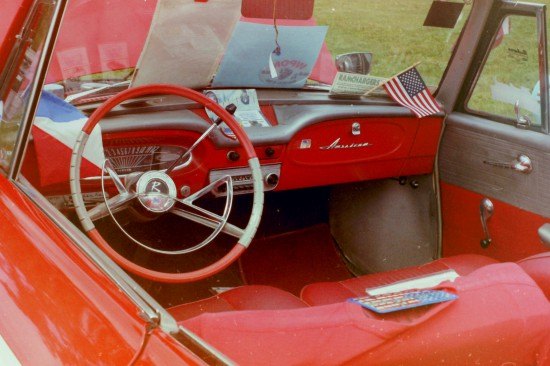

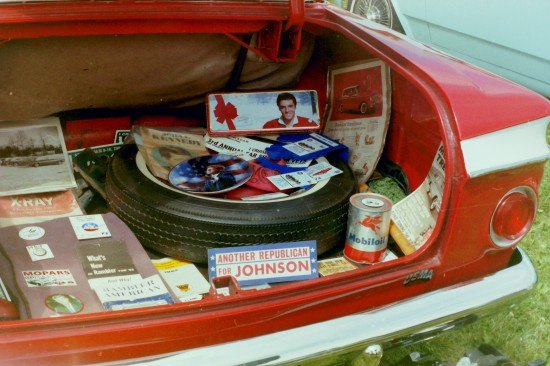

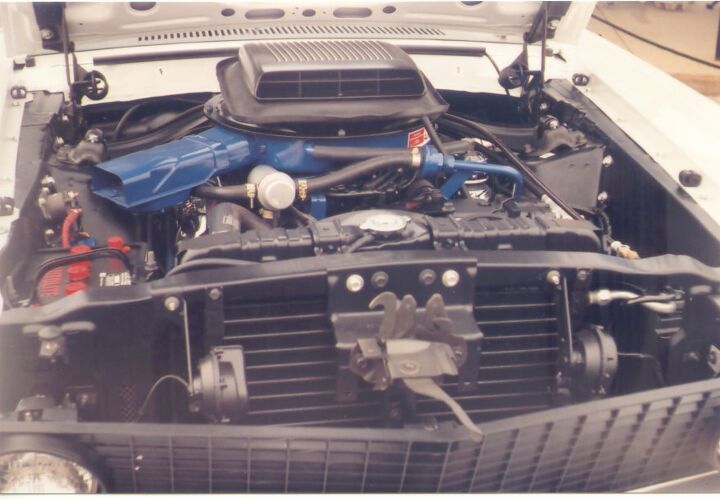

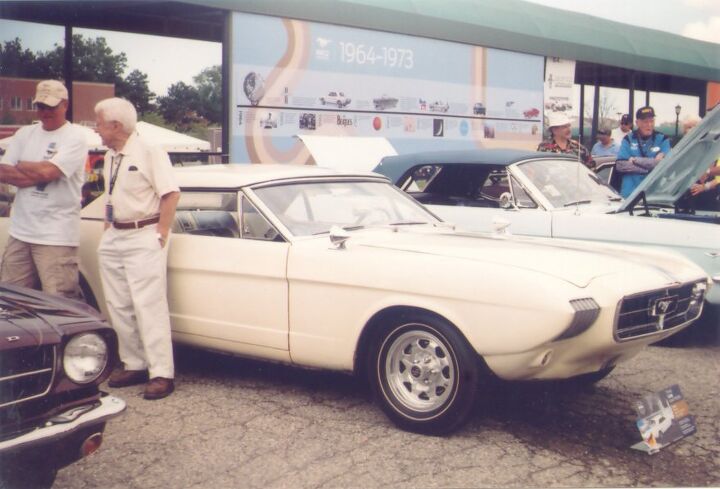

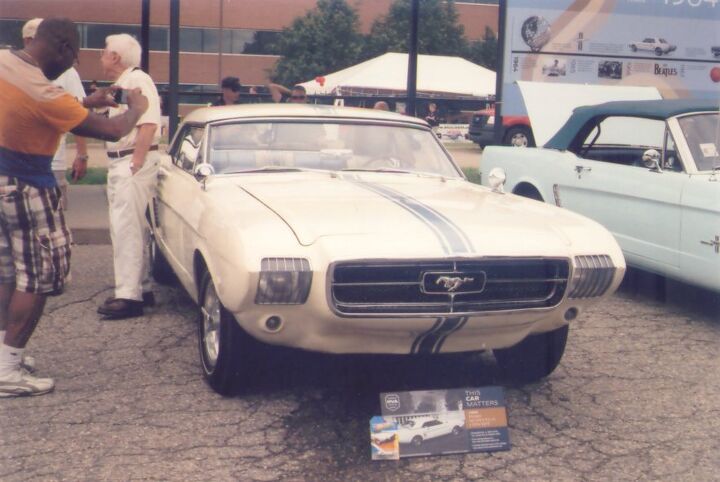

There was a 1962 Rambler American convertible at the AMC show. My dad owned a 1961 Rambler American sedan, so it seemed appropriate to use the camera he owned back then to shoot little ragtop car. As you can see, the results weren’t too bad. The shots that I took of the 1963 Mustang II concept and Larry Shinoda’s personal Boss 302 prototype at the Mustang Memories show also came out well. I was a bit concerned that the Argus might not be “light tight” because the simple spring-metal catch for the back has lost some tension over the years and has to be bent back out to hold the back on tight, but the results show that the 57 year old camera can still take fine phototgraphs.

It may work fine, but it was meant to work fine in a different era. In the time that it takes to compose, frame, focus, set aperture and shutter speed to take a single photograph with the Argus, I can take an entire series of photos, most with better focus and exposure, in 3D yet, and get them cropped and uploaded so that you can be enjoying them while I’m still on my way to the camera store to get that film developed.

A note about the scanned photos. I wasn’t happy with the results from scanning the prints with my flat bed scanner, which I should probably replace. In addition to scanning the prints, I also used the inexpensive slide scanner that I have to scan the original negatives. Those results were better and in much higher resolution, though there were some issues with dust particles in that scanner. Also, the scanner software picked some curious defaults for color selections and I’m not adept at color correction. The actual prints from the new film in the Argus actually came out rather well, with very vivid and true to life hues. On the shots taken with the Konica at the Charger Hellcat reveal, I played with the software to boost the exposure to make a second set.

While that Rite Aid / Fuji film was inexpensive, and while both the Argus and Konica cameras still work pretty well, processing and printing runs about $10 for a 24 exposure roll. Right now at MicroCenter you can buy a 16 gigabyte SD card for that same ten bucks. The 8 megapixel Canon SD850s digital cameras in my still photography 3D rig can put between 900 and 1,000 images on the 4 GB memory cards that I use. For the same cost as shooting one roll of color film, I can shoot thousands of digital photos, but then with digital I can transfer those photos to my desktop computer (or the cloud) and shoot thousands more photos on the same media. Getting high resolution color photos to other people almost instantaneously isn’t the only reason to use digital photography.

For more on the history of Argus and their cameras, this article at Shutterbug.com is a good start. The Argus Collectors Group site has manuals if you have a “Brick” in the attic and want to use it. The Ann Arbor District Library also has a comprehensive sub-site devoted to Argus. If you’re in Ann Arbor, the Argus Museum is located in one of the company’s former buildings at 525 West William Street, on the second floor.

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, a realistic perspective on cars & car culture and the original 3D car site. If you found this post worthwhile, you can get a parallax view at Cars In Depth. If the 3D thing freaks you out, don’t worry, all the photo and video players in use at the site have mono options. Thanks for reading – RJS

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, the original 3D car site.

More by Ronnie Schreiber

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Kwik_Shift_Pro4X I will drive my Frontier into the ground, but for a daily, I'd go with a perfectly fine Versa SR or Mazda3.

- Zerofoo The green arguments for EVs here are interesting...lithium, cobalt and nickel mines are some of the most polluting things on this planet - even more so when they are operated in 3rd world countries.

- JMII Let me know when this a real vehicle, with 3 pedals... and comes in yellow like my '89 Prelude Si. Given Honda's track record over the last two decades I am not getting my hopes up.

- JMII I did them on my C7 because somehow GM managed to build LED markers that fail after only 6 years. These are brighter then OEM despite the smoke tint look.I got them here: https://www.corvettepartsandaccessories.com/products/c7-corvette-oracle-concept-sidemarker-set?variant=1401801736202

- 28-Cars-Later Why RHO? Were Gamma and Epsilon already taken?

Comments

Join the conversation

I'm a 'digital' guy so some say. But also 'analog', as I love film. I use both often. For me it's not digital or film photography, it's which one for what situation. I tend to use film for more personal work for my own enjoyment, even use it for walkaround snaps, but digital for "work". I just don't find digital all too much fun. I find... I tend to take much more boring and more numerous photos with a digital camera, just because I can. I like the fully manual nature of some of the film cameras, but I also like semi assisted and fully assisted automatic film and digital cameras. Fully manual film can be exhausting sometimes for impromptu street photography, with calculating exposure based on available light and fixed ISO, setting the aperture and shutter speed to a setting based on a possible subject coming into the frame. Possible variations based on direction of the sun, cuz old glass might have different flare properties. Calculate distance of subject for focus, and if they are in the hyperfocal focus range of the particular lens you mounted, compose, all within 2 seconds of snapping a photo. I don't do a lot of colour film but usually it's under $5 for develop, I dont usually have use for machine prints until after development. I do my own black and white film processing, mostly shoot 120 roll film, with small amounts of 35mm and sheet film. I still buy enthusiast level digital camera equipment often enough, but still buy used film cameras all the time.

actually 126 is pretty darn good at 28x28mm (compared to 24x36mm for 135 film), it's 110 that's small at 13x17mm. There were a few good 126 cameras, even 110 had some decent SLR's but indeed most were crap. Dont get me started on ridiculous small disk film negs!