Was the First Batmobile a Coffin Nosed Cord or a Graham "Sharknose"? Part Two

1939 Graham Model 96. Full gallery here.

To recap from Part One, I wasn’t planning on revisiting the issue of which car did Batman artist Bob Kane use as a basis for the first Batmobile, a Cord 812 or a Graham “Sharknose”. However, I was going through some photos that I took last summer and when I saw these shots that I took of the 1939 Graham Model 86 at the 2013 Concours of America at St. John’s, I thought that I’d share them and the story of the car with you. It’s such a departure from the cars of its day and its styling is so dramatic that I’m surprised that it’s not better known. I think the Sharknose is one of the coolest car designs ever and as I mentioned in Part One the Batmobile thing is as good an excuse as any to write about the Graham and the men who made it. Here’s the Sharknose’s story.

Joseph, Robert and Ray Graham were born in the 1880s on their family’s Indiana farm. In 1901, after natural gas deposits were discovered nearby, Joseph and his father invested in a glass bottle making company that planned on using the fuel as an energy source in the process. When only 19 years old, Joseph had invented a new way of mass producing blown glass bottles that produced stronger bottles and the firm thrived. They expanded horizontally and vertically and by 1916, Owens Bottle Company of Toledo, Ohio suggested a merger. Later that merged company became known as Libbey Owens Ford.

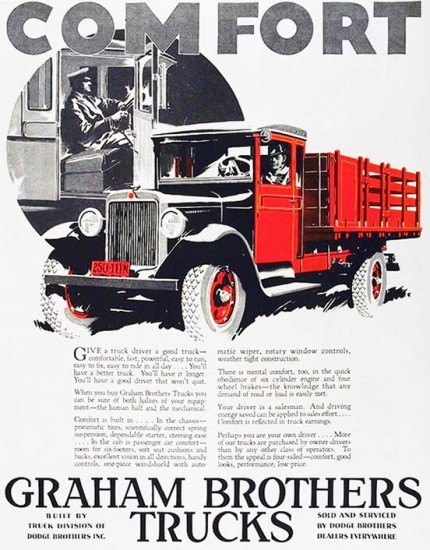

Ray Graham meanwhile graduated from the University of Illinois and started managing the family’s agricultural properties. Realizing that farmers needed light trucks, he designed a special rear axle and subframe that could be spliced into Ford Model T cars to create one ton stake or express (what we’d call a pickup) trucks. The conversion kit sold for $350 and did well enough that Ray’s two brothers sold their interest in the glass company to Owens and together the Graham brothers set up a factory in Evansville, Indiana to build truck bodies to convert automobiles to commercial vehicles. By 1920 they were assembling complete Graham Brothers trucks and buses, using a variety of engine suppliers, including Dodge. With their background making bodies, unlike most truck makers, they sold complete vehicles, offering a variety of bodies customized for particular industries.

By then the Dodge brothers had died within months of each other and the Dodge Brothers company was being managed by Fred Haynes, who had been the Dodges’ right hand man. Haynes wanted to expand Dodge’s truck business but didn’t want to disrupt car production or take on the expense of building a new factory. In 1921, an agreement was made that the Grahams would exclusively use Dodge supplied powertrains in their trucks which would then be sold through the nationwide Dodge dealer network. It was a deal too good to turn down, getting associated with one of the biggest passenger car companies and being marketed by their many dealers. It was a great deal for the Grahams, and production rose from 1,086 trucks in 1921, to over 37,000 units just five years later. Graham Brothers became the largest truck-only manufacturer in the world.

After the Dodge brothers’ widows sold their company to an investment bank, the firm was reorganized, with all three Grahams becoming vice presidents and directors of Dodge. Dodge then exercised their option to buy a controlling interest in the Grahams’ firm for $3 million plus stock options on Graham Brothers shares. The brothers invested much of that money back into Dodge stock, becoming two of the company’s largest shareholders.

Six months later, though, they parted company with Dodge and sold the remaining 49% of Graham Brothers to the automaker. It’s not known exactly why they left Dodge but it’s thought that they wanted to make their own automobiles and knew that wouldn’t be possible as long as they were affiliated with Dodge.

Between their holdings in the automotive and glass industries, the Grahams were wealthy twice over and indeed decided to get into the car industry more directly. They bought control of the Paige-Detroit Motor Car Company, an independent automaker that had operated since 1909, selling as many as 43,000 cars and trucks a year under the Paige and Jewett brands. The Jewett family which controlled the company was anxious to sell because sales had started to decline in the mid 1920s. One reason why the Grahams were interested in Paige was because it had just finished building a completely new and modern factory on Warren Avenue in Dearborn. That building, by the way, still stands and houses a company that produces hummus and other Middle Eastern foods. Putting up $8 million to buy and improve the company, the Grahams renamed the firm to Graham-Paige Motors Corporation.

One reason for their success was that the Graham brothers had distinctive but complementary personalities and talents. They were well known at the time and were considered the peers of other successful automotive families like the Fishers, Dodges, Duesenbergs and Studebakers.

Though they kept making Paige automobiles, within six months they had new, Graham branded cars on the market. The new Grahams were received favorably by the motoring press, impressed by their four speed transmissions, a feature usually reserved for more expensive cars. Sales soared from 21,881 in 1927 to 73,195 the following year and 77,000 in 1929. Graham-Paiges weren’t appreciably different from other cars of that era, but they were well made and a good value for the price. The company competed in endurance runs and rallying, with some success and attendant publicity.

Then the stock market crashed. Production dropped by more than half in 1930. Paige was dropped from the company name after that model year. They tried their hand at making trucks again, but Walter Chrysler, who had acquired Dodge by then, sued, claiming that it violated their sales agreement with Dodge for their truck company so they stopped making trucks with the 1932 models.

Pressing on despite the bad financial times, the Grahams decided that the solution to their sales slump was the Blue Streak Eight. Designed by Murray Corp. chief stylist Amos Northup, with additional details by famed coachbuilder Ray Dietrich (Dietrich Inc. had been bought by the Murray body company), though it looks fairly conventional to our eyes, the Blue Streak was almost radical for the day. It was one of the most influential car designs of the era.

One of the first car bodies to be designed to appear as a whole rather than assembled parts, the Blue Streak was two inches lower than previous models, with graceful and flowing lines. The radiator grille, which hid the typically exposed radiator shell, slopes back, a theme echoed in the hood louvers and the rake of the one piece windshield. The radiator cap was hidden as well, though some owners mounted mascots, perhaps the first true hood “ornaments”, as previous mascots functioned as radiator caps. Chrome plated brightwork was kept to a minimum and the headlamp shells were painted the same color as the body, not plated. Significantly, the Blue Streak was the first prominent production car to have deeply drawn and skirted fenders, which hid the frame and the grimy undersides of the front wings. That feature became widely copied and Graham even advertised itself as the most imitated car company. The chassis of the Blue Streak, designed by Graham engineer Louis Thoms, featured “banjo” openings to contain the rear axle. This produced a much stronger frame and the outboard placement of the springs allowed for a lower, more stable car.

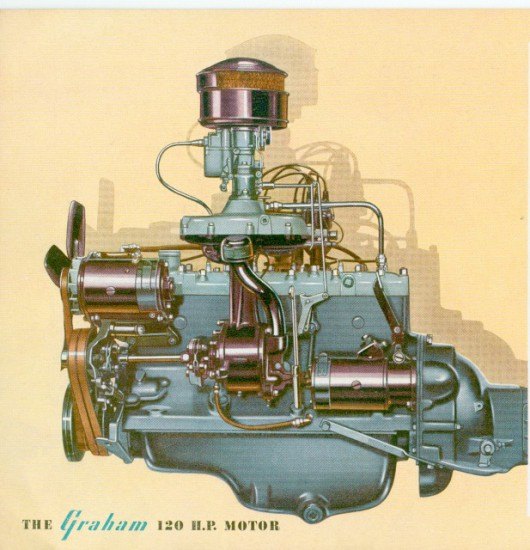

Considered one of the most beautiful cars of the 1930s, the Graham Blue Streak might have been an aesthetic success, but it was no match for the Depression and sales continued to drop. You have to give the Grahams credit, though, because they continued to innovate, introducing a production supercharged engine for the 1934 model year. Graham was the first automaker to offer a supercharger on a moderately priced car, blowers previously only being available on costly automobiles like Duesenbergs, Stutzes and air-cooled Franklins. As a matter of fact, Graham engineer F. F. Kishline more or less copied the Duesenberg’s centrifugal supercharger, as did the design of the supercharger used on the Cord 812’s Lycoming engine. The Graham blower, like those on Duesenbergs and Cords, was located between the carburetor and the intake manifold, driven by the engine’s accessories shaft and pressure lubricated. Graham advertised their engines as “Graham-built”, to distinguish themselves from other car companies that bought complete engines from suppliers like Continental. Graham did buy short blocks from Continental, but they were made to Graham specifications and then built up by Graham with aluminum cylinder heads of their own design and manufacture, along with the supercharger, the carburetor, accessories, and wiring.

The supercharger did result in a substantial boost in power from 95 to 135 hp, with a concurrent 20% increase in torque, to 210 lb-ft. Top speed was above 90 mph and the UK’s The Autocar magazine published a 0-60 mph time of 15.8 seconds. The magazine said that engine performance “is extremely good, especially considering that the engine is not a monster unit. [The Graham] is not in the least noticeable as being a supercharged car in the sense to which we are accustomed on some machines. Anyone driving this Graham without knowledge of the design would find nothing in the car’s behavior, no added noise, no fussiness of the engine-to denote any difference whatsoever from the general run of similar machines.”

If you’re reading this you’ve probably heard the name “Cannonball” Baker, most likely because of the unsanctioned coast to coast “Cannonball Baker Sea-To-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash” or the related movies. Erwin “Cannonball” Baker was a motorcycle and car racer and daredevil who made a series of long distance and coast to coast record runs on two and four wheels, typically sponsored by the manufacturer of the vehicle he used (Baker promised sponsors, “no record, no money”). To promote their new supercharged engine, in 1933 Graham-Paige hired Baker to drive a supercharged Blue Streak Model 57 across the continent and he set a record, 53 hours and 30 minutes, that would stand for almost 40 years, until the team of writer Brock Yates and racer Dan Gurney inaugurated the “Cannonball Baker Sea-To-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash” in 1971 with a coast to coast run of 35 hours and 54 minutes.

While it’s a notable point in American automotive history, Cannonball Baker’s record run didn’t do much to change the fortunes of the Graham company. As the Depression wore on, sales continued to slide. Company directors decided that they needed to make a car whose styling was as dramatic as its performance. For the 1938 model year, they again engaged Amos Northup and he designed a series of cars that the Graham company called “The Spirit of Motion”.

In the December 1928 issue of Autobody magazine, Northup published an essay titled “Motor-Car Design of the Future”. In it he said, “I sincerely believe that by closer cooperation between motor-car designer and chassis engineer, our future cars will each have more of an individual appearance than at present, when at a certain distance, it is difficult to distinguish their identity.” The 1938 Graham lived up to that philosophy and certainly had an individual appearance.

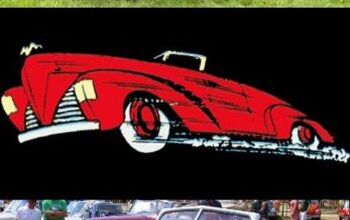

The front fenders and the radiator grille were undercut, leaning forward, giving the impression that the car was moving even as it was sitting still. The forward leaning grille led to the somewhat mocking nickname of “Sharknose”, but it also made the 1938 Grahams stand out in a era that many consider to have had very conformist automotive styling.

The new bodies were exactly that, completely new. Not a single stamping die was carried over from previous Grahams. In addition to the novel sheetmetal styling, another feature that set the ’38 Grahams apart from their contemporaries were flush mounted headlight housings with square lenses, an early attempt at unique headlamp shape when designers were severely limited by round lighting elements. It would be decades before square or rectangular headlamps would reappear on motor vehicles.

A smooth line flows from the horizontal grille louvers back into the hood and along the side of the car, becoming the belt molding, which integrates the door handle in its sweep. The rear fenders had full skirts and the split windshield was peaked. The taillights were also novel, sitting just aft of the C pillars, flush mounted into the body above the integral trunk, for better visibility. For a car with such dramatic front end styling, the rear ends of the ’38 and ’39 Grahams were a bit clunky to my tastes, with the bulky trunk looking much too conventional compared to the front end, however, the high mounted taillights allowed Northup to draft a very clean looking rear end, a custom hot rod touch before there were custom hot rods.

While they never went into production, apparently a number of supercharged convertible coupes were made by Graham as design studies for a possible open top model. One of them was in the well regarded collection of the late trial lawyer, John O’Quinn. While there were some coachbuilt convertible Grahams, including an even more radical body by French custom body builder Saoutchik that had parallel opening doors like a minivan and a large tailfin, close examination reveals that the O’Quinn and similar Graham Sharknose convertibles were indeed built in house by Graham and fully engineered.

The convertible Sharknoses are great designs. There is one continuous line from the nose of the car, to the belt line to a beautifully tapered rear end, which incorporates a subtle boattail. The way the tail end of the rear fender and chrome taillight housing stand proud of the trunk look a little like proto-tailfins and remind me of the 1948 Cadillac that is usually credited with introducing fins on cars.

The radical new body sat on a new chassis. Using a hypoid rear axle gear (whose drive gear sits at the bottom of the case) eliminated the driveshaft tunnel in the back seat even though the floor was already two inches lower than on preceding models. Flipping the transmission on its side reduced its own intrusion into passenger space. Smaller frame rails allowed the body to sit lower, with an additional crossmember to keep things rigid. The Graham Gyrolator, the company’s term for an anti-sway bar, had been introduced in 1936 and was carried over. Under the hood, supercharged engines got a new carburetor with three venturi tubes, intended to eliminate blower lag.

Maybe the Graham Sharknose was ahead of its time. Today, looking like a shark isn’t a disadvantage for a car. I recently observed a 2015 Mustang GT getting tested in a wind tunnel and the Ford engineers and designers frequently referred to the Mustang’s forward leaning grille as its “shark nose” and consider that styling element to be a basic ingredient in what makes a Mustang a Mustang.

Perhaps the styling was too radical, like the Chrysler Airflows that came out only a few years before the Graham Sharknose. Perhaps it was the economy. By 1937, the Depression had eased a bit, but 1938 brought a deep recession (brought on, say both those on the political left and on the right, by the economic policies of the Roosevelt administration) that hurt a lot of automakers. Pierce-Arrow stopped production. Hupp was mortally wounded. Whatever the reason, the 1938 Grahams were not a hit with consumers.

Northup, incidentally, never lived to see the Sharknose’s poor reception. In February 1937, when the design of the new Graham was almost completed, he went out for a newspaper, slipped on an icy sidewalk, fell and hit his head. He died a few days later at the age of 47, likely from a cerebral hematoma/hemorrhage.

The Graham car company had only made money in two years since the company was founded in 1927 but the failure of the radical 1938 models to find a market put the company’s future in jeopardy. In 1938 company officials, including Joe Graham, met with creditors and suppliers to arrange financing so they could produce the 1939 models. Joseph Graham personally put up $560,000 of his own money to keep the company going. Some new variants of the Sharknose body were introduced for the 1939 model year. The economy picked up slightly and production rose to 6,557 for the model year but it wasn’t enough to keep the company going and the plant was shut down in July of 1939.

Graham ended automobile production for good in November of 1940. The company survived on government defense contracts in the runup to and prosecution of the war with Germany and Japan, but after WWII it divested its industrial holdings, concentrating on real estate. For a while, Graham’s corporate heirs owned Madison Square Garden in New York City and eventually the firm became part of a large real estate conglomerate.

Once you get past the front end, you can tell that the Graham Hollywood was based on Gordon Buehrig’s Cord. Full gallery here.

There is, by the way, another connection between Cord and Graham besides superchargers and comic book cars. Before Graham ended car production for good, they were part of a deal involving the body dies used to stamp out Cord panels. Having spent a goodly sum developing the flopped Sharknose, Graham couldn’t afford a new body to replace it. A deal was struck so that Graham would make bodies based on the out of production Cord for both themselves and for Hupp. Pioneering designer John Tjaarda was tasked with restyling the Cord’s coffin nose into something more conventional. The result was attractive in a late 1930s idiom, if not quite as nice looking as the Cord, and Hupp Skylarks and Graham Hollywoods occupy their own niche in the collecting world, even if they didn’t save Hupp or Graham as automobile manufacturers. You can read more about the Cord bodied last Hupmobiles and Grahams here.

Since the factory built Graham convertibles appear to have first surfaced publicly in the 1950s, it’s likely that Kane didn’t pattern the rear end of the first Batmobile on those cars as he probably never saw them. He could have used the back end of the Cord convertible as inspiration, or the Packard Darrin, which has a similar rear end as the Cord and Graham convertible, or any one of a number of late 1930s cars with that kind of tapered styling. The front end and headlights, though, and some of the other features of the comic book car, still look to me that they were undoubtedly inspired by the shark nosed Graham, not the coffin nosed Cord.

What do you think?

Acknowledgements:

Much of the historical material on Graham-Paige in this post was drawn from an article by Jeffery I. Godshall in Automobile Quarterly Volume 13 No.1 (out of print, reproduced here).

Special thanks to Mischa Lohr, aka Zappadong, who graciously allowed us to use his photographs of the Graham Model 97 Convertible. Check out his enormous collection of photos of all kinds of cars (full size and toy) on Flickr.

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, a realistic perspective on cars & car culture and the original 3D car site. If you found this post worthwhile, you can get a parallax view at Cars In Depth. If the 3D thing freaks you out, don’t worry, all the photo and video players in use at the site have mono options. Thanks for reading – RJS

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, the original 3D car site.

More by Ronnie Schreiber

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Groza George I don’t care about GM’s anything. They have not had anything of interest or of reasonable quality in a generation and now solely stay on business to provide UAW retirement while they slowly move production to Mexico.

- Arthur Dailey We have a lease coming due in October and no intention of buying the vehicle when the lease is up.Trying to decide on a replacement vehicle our preferences are the Maverick, Subaru Forester and Mazda CX-5 or CX-30.Unfortunately both the Maverick and Subaru are thin on the ground. Would prefer a Maverick with the hybrid, but the wife has 2 'must haves' those being heated seats and blind spot monitoring. That requires a factory order on the Maverick bringing Canadian price in the mid $40k range, and a delivery time of TBD. For the Subaru it looks like we would have to go up 2 trim levels to get those and that also puts it into the mid $40k range.Therefore are contemplating take another 2 or 3 year lease. Hoping that vehicle supply and prices stabilize and purchasing a hybrid or electric when that lease expires. By then we will both be retired, so that vehicle could be a 'forever car'. Any recommendations would be welcomed.

- Eric Wait! They're moving? Mexico??!!

- GrumpyOldMan All modern road vehicles have tachometers in RPM X 1000. I've often wondered if that is a nanny-state regulation to prevent drivers from confusing it with the speedometer. If so, the Ford retro gauges would appear to be illegal.

- Theflyersfan Matthew...read my mind. Those old Probe digital gauges were the best 80s digital gauges out there! (Maybe the first C4 Corvettes would match it...and then the strange Subaru XT ones - OK, the 80s had some interesting digital clusters!) I understand the "why simulate real gauges instead of installing real ones?" argument and it makes sense. On the other hand, with the total onslaught of driver's aid and information now, these screens make sense as all of that info isn't crammed into a small digital cluster between the speedo and tach. If only automakers found a way to get over the fallen over Monolith stuck on the dash design motif. Ultra low effort there guys. And I would have loved to have seen a retro-Mustang, especially Fox body, have an engine that could rev out to 8,000 rpms! You'd likely be picking out metal fragments from pretty much everywhere all weekend long.

Comments

Join the conversation

Hi Ronnie, Great articles and really interesting stuff. One detail correction I'd like to point out - which you gloss over in the first article - the real illustrator of Batman was not Bob Kane but was Bill Finger. A friend of mine, who is an author, has written a book (for kids and adults) about Bill Finger and some of the uncredited history related to Batman. The book is titled "Bill the Boy Wonder" by Marc Nobleman. Also, I can point you to Marc's blog, where he talks about various efforts to get credit for Bill Finger's contributions: http://noblemania.blogspot.com/2014/02/bill-finger-google-doodle-den-of-geek.html I'm sure Marc would be more than happy to help provide you any resources on the illustrations for Batman and whatever he knows about the Batmobile.

So pretty ! . I'm no big fan of drop tops but that Shark Nose DHC would look perfect with a low slung Carson Top on it.... -Nate