Venezuela's Gasoline Prices May Rise to $1.60 a Gallon, From 5 Cents

As Venezuela faces an economic crisis that is depleting government coffers, President Nicolas Maduro is threatening to end something many citizens of that oil producing country consider to be their patrimony, incredibly cheap gasoline, the equivalent of 5 U.S. cents per gallon. That price hasn’t changed in almost two decades. In 1989 the price of gasoline was raised, prompting deadly rioting that went on for days and killed over 300 people. To keep the retail price that low, the government subsidizes gasoline to the tune of more than $12.5 billion a year. The result is that Venezuelans aren’t interested in small, clean, fuel efficient cars. Big old sedans, 1970s era trucks and newer SUVs dominate Venuzuelan roads, compounding both the amount of subsidies needed and the smog over Caracas.

That nickel-a-gallon price is at the official currency exchange rate but if you sell your dollars on the widely-used black market, a gallon of gas could cost you less than a penny.

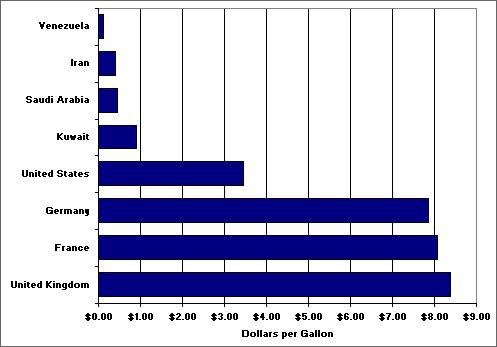

“Prices are so cheap in Venezuela that they may make Saudi Arabia and Iran look expensive,” said Lucas Davis, a University of California-Berkeley energy specialist.

It’s unknown how much Maduro will raise the price. While the country has an authoritarian government, Maduro still doesn’t want to rile up Venezuelans already pinched by an inflation rate of 54% and the collapse of the bolivar, the country’s currency.

The idea of Venezuelan’s paying more for gasoline was first floated in early December, when Vice President Jorge Arreaza said it was time start discussing raising gas prices. Oil Minister Rafael Ramirez said that the country having the world’s cheapest gas wasn’t a point of pride. Finally, last week Maduro himself said he favored gradually raising prices over three years.

“As an oil nation, Venezuelans should have a special price advantage for hydrocarbons compared to the international market,” the former bus driver told newly elected mayors on Dec. 18. “But it has to be an advantage, not a disadvantage. What converts it into a disadvantage is when the tip you give is more than what it cost to fill the tank.”

Venezuela’s budget deficit is estimated at 11.5 percent of gross domestic product, one of the highest in the world.

Unlike Cuba’s fleet of 1950s era American cars, Venezuela’s clunkers are mostly undesirable ‘malaise era’ Chargers and Malibus, some held together with rope and bailing wire, used as unregulated taxis.

If prices rise to what the government says is needed to cover the cost of production, a liter would cost around 2.50 bolivars, about 40 cents on the dollar at the official exchange rate. That would work out to about a buck sixty a gallon. By comparison, bottled water costs 12 bolivars a liter.

More by TTAC Staff

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- ToolGuy TG likes price reductions.

- ToolGuy I could go for a Mustang with a Subaru powertrain. (Maybe some additional ground clearance.)

- ToolGuy Does Tim Healey care about TTAC? 😉

- ToolGuy I am slashing my food budget by 1%.

- ToolGuy TG grows skeptical about his government protecting him from bad decisions.

Comments

Join the conversation

A taxi fleet of Malaise era Chargers and Malibus sounds just like DC!

It will be interesting to see what will be the outcome of this. The decision to raise gasoline prices is certainly the right one, as this is one of the only few sources of revenue for the government. The economies of South America often have a large informal sector which is hard to tax. So even though there is plenty of economic activity, very little of it contributes to the government's coffers. Venezuela's problems are compounded by the large and inefficient public sector which creates a big cash drain for the government. Venezuela's economy is basically on the brink of collapse, with run-away inflation, probably caused by printing too much currency, artificially overvalued domestic currency, which can collapse every day now, and shortages of many basic goods, such as toilet paper. The country is a perfect case of resource curse. It's amazing that despite being one of the biggest oil exporters in the world, they managed to mismanage the economy so badly. Even Arabs know that their oil will run out eventually, and started to invest aggressively in non-oil portions of their economies.