Found In Kalamazoo: The Astroghini, Tales Of America's Industrial Past

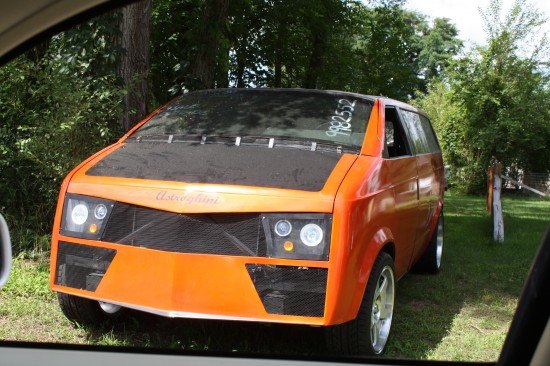

You know what I could really go for? A turbocharged Astro modified to, er, “look like a Lamborghini”. A show called “Ultimate Car Build” created such a vehicle a year or so ago. The “Astroghini” ran from 0-60 in 6.2 seconds thanks to a turbocharger sitting in place of the passenger seat. It sold on eBay in September, but the precise whereabouts of the Astroghini were unknown… until now. It sits just a few miles from a General Motors plant which closed in 1999 and nearly put the surrounding community down for the proverbial count.

Long-time TTAC readers will recall my mention of the Heritage Guitar Corporation in an article on MB-Tex guitar straps. This past weekend, I attended the the “Parsons Street Pilgrimage”, an annual visit to the Heritage’s production facility in basement of Gibson’s Kalamazoo factory. I knew the factory trip would be a treat, most notably because Heritage founder Marv Lamb had just completed an H-357 “Firebird” made from Korina wood and flame maple just for me. He’d also agreed to install a set of Jon Gundry’s ThroBak MXV SLE-101 Plus pickups in the thing. Mr. Gundry is a fanatic about correctly reproducing the sound of Gibson’s vintage “PAF” pickups, and every piece of a ThroBak, from the magnets to the maple internal spacer, is sourced from local suppliers in Michigan. Best of all, the whole thing is wound on Gibson’s original “Slug” and Lessona winders.

In an era where most of the junk one buys is precisely that — junk, and from China to boot — I was inordinately pleased to know that I would have a guitar assembled using the methods, machines, and people who worked at Gibson some fifty-three years ago. Before I could visit Heritage’s basement facility, however, I had to stop by Aaron’s Music Service. Back in January, I’d taken a chance on buying a broken-necked Heritage “Eagle Classic” jazz guitar from a doctor in Kalamazoo, and Aaron Cowles, the owner of Aaron’s Music Service, had agreed to take on the project of building a new neck and rebuilding the rather fragile instrument from the braces up. After seven months, Mr. Cowles believed the Eagle had finally risen from the ashes, to mix a metaphor.

Kalamazoo has been on the losing end of America’s long slide into Third World “globalism” for a while now. Gibson left in 1983, attracted by the “right to work” environment in Tennessee. Today, although the Nashville and Memphis plants turn out plenty of new American-made guitars, Gibson as a company has staked its existence on a brand new plant in — you guessed it — Qingdao, China, where the lower-cost “Epiphone” line is made. An Epiphone Firebird guitar costs $449. The Nashville-made Gibson Firebird, chopped out in record time by CNC machines and assembled as quickly as two decades’ worth of process improvements can manage, costs $1,699. A Heritage 357 Firebird, made by one man over the course of a month or two using hand tools and rough jigs, is considerably more costly than the machine-made Gibson. This isn’t the kind of math that bodes well for American manufacturing. Luckily, guitar players are sentimental people and once they can afford to put down the Chinese stuff and buy a local product they usually do so.

If only the car-buying populace was as sentimental. General Motors opened the Fisher Body stamping plant in 1964 and closed it in 1999. Like Gibson, GM sees its future in China. The white-collar employees who fiddled while GM sent more and more jobs to Mexico and other overseas locations eventually found out that they were playing the role of the infamous Pastor Niemoller; when engineering for projects like the Cruze and Sonic moved to Daewoo, many American engineers and managers found themselves looking for work.

Abandoned by GM, Kalamazoo has fought back. The unemployment rate, an almost unbelievable 2% in 1999 before the GM plant closed, is now nine percent. Still, that’s better than the Michigan state average of 11%. The bad news: both of those numbers are trending sharply up even though Kaiser Aluminum opened up in the old Fisher Body plant two years back and has added a couple of thousand jobs to the local mix.

My first reaction on seeing the “Astroghini” in a roadside yard was that someone in K-zoo had built the thing, and I honestly wasn’t all that surprised. Over the course of three days, I saw a lot of modified cars, a lot of custom motorcycles, a lot of well-restored vintage Fifties and Sixties Chevrolets. This isn’t New York or Seattle. People build, create, fix, restore here.

Aaron Cowles opened his shop in the early Nineties. He’d been a Gibson employee for nearly twenty years prior to that. After some mild prompting on my part, he began to tell tales about working for Gibson in what were commonly considered the “dark days” of the Seventies. Having started his career in Kalamazoo literally sweeping floors for the company, he ended up doing binding and finish work, as well as building mandolins in their entirety. When Gibson announced the opening of the Nashville plant, he knew that his days with the company were probably limited.

“They didn’t offer us a chance to move to Nashville… we were union, we made too much money. The people in Nashville earned a third of what we did, and they were glad to have the work.”

On Aaron’s wall, a series of black-and-white photos document his time with Gibson. Aaron is a serious, handsome young man in the pictures; he looks like the quintessential Golden Era American and it’s easy to imagine him building a B-24 bomber or, indeed, flying one over Germany. A color snapshot tucked into the corner of the bottom photo tells the end of the story. In this one, a sixty-ish Aaron is standing with a heavy, balding young man in safety glasses.

“I traveled down to see the Nashville shop a few years ago,” Aaron recalls, “and they let me meet the man who does my job now. He works really hard. Nice fellow. It isn’t really a living like it used to be, though. The Gibson plant paid well. I sent my kids to school on that job, bought house. It was solid, steady work and I was proud to be there.”

There’s a pause, and Aaron looks at me, perhaps to make sure that I am listening — that the callow, long-haired hippie/yuppie standing before him, the guy who barely knew who Chet Atkins was, the fellow who had commissioned a rather serious rebuild project over the phone and hadn’t really even asked the right questions — that I was really paying attention.

“The Gibson plant was solid, steady work,” he repeats. Another pause, and his eyes lose their focus.

“Of course, it wasn’t as good as working for GM.”

More by Jack Baruth

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- 3-On-The-Tree 2014 Ford F150 Ecoboost 3.5L. By 80,000mi I had to have the rear main oil seal replaced twice. Driver side turbo leaking had to have all hoses replaced. Passenger side turbo had to be completely replaced. Engine timing chain front cover leak had to be replaced. Transmission front pump leak had to be removed and replaced. Ford renewed my faith in Extended warranty’s because luckily I had one and used it to the fullest. Sold that truck on caravan and got me a 2021 Tundra Crewmax 4x4. Not a fan of turbos and I will never own a Ford again much less cars with turbos to include newer Toyotas. And I’m a Toyota guy.

- Duke Woolworth Weight 4800# as I recall.

- Kwik_Shift_Pro4X '19 Nissan Frontier @78000 miles has been oil changes ( eng/ diffs/ tranny/ transfer). Still on original brakes and second set of tires.

- ChristianWimmer I have a 2018 Mercedes A250 with almost 80,000 km on the clock and a vintage ‘89 Mercedes 500SL R129 with almost 300,000 km.The A250 has had zero issues but the yearly servicing costs are typically expensive from this brand - as expected. Basic yearly service costs around 400 Euros whereas a more comprehensive servicing with new brake pads, spark plugs plus TÜV etc. is in the 1000+ Euro region.The 500SL servicing costs were expensive when it was serviced at a Benz dealer, but they won’t touch this classic anymore. I have it serviced by a mechanic from another Benz dealership who also owns an R129 300SL-24 and he’ll do basic maintenance on it for a mere 150 Euros. I only drive the 500SL about 2000 km a year so running costs are low although the fuel costs are insane here. The 500SL has had two previous owners with full service history. It’s been a reliable car according to the records. The roof folding mechanism needs so adjusting and oiling from time to time but that’s normal.

- Theflyersfan I wonder how many people recalled these after watching EuroCrash. There's someone one street over that has a similar yellow one of these, and you can tell he loves that car. It was just a tough sell - too expensive, way too heavy, zero passenger space, limited cargo bed, but for a chunk of the population, looked awesome. This was always meant to be a one and done car. Hopefully some are still running 20 years from now so we have a "remember when?" moment with them.

Comments

Join the conversation

Great piece! And a helluva fine looking guitar. Gibson lost me during their more recent transition to house-brand for Guitar Center. That dealer cull was something I wouldn't be surprised to see from GM. Luckily there are some great USA guitars and basses still made, like Heritage and G&L.

Bringing this back from the dead. I am a native of Kalamazoo and avid reader of TTAC. I recently stumbled upon the astroghini. For sale locally for $4400!! What a steal!