The Case Against Akerson, Part 2 of 3: Lack Of Strategy

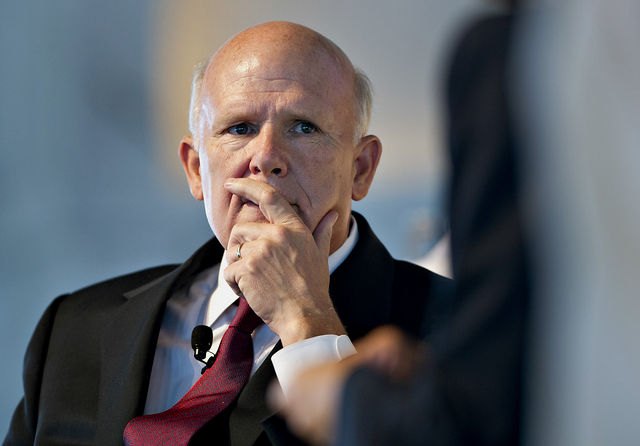

In the first part of this series, we looked at Dan Akerson’s problematic relationship with the truth, focusing on the gap between his stated intentions and his actions. Akerson is hardly the only example of an auto executive to indulge in personal myth-building or ego-driven dissembling. Analysts, employees and shareholders can forgive all kinds of personal shortcomings in a chief executive so long as he has a clear plan for success and the proven ability to get results. Unfortunately for GM, Dan Akerson brings nothing to the table in this regard that might outweigh his negatives.

The depth of Akerson’s strategic failure is nothing short of stunning, encompassing almost every element of GM’s global footprint.

From China to North America, from Europe to the developing world, General Motors is not only failing to take advantage of its fresh start, it is mortgaging its future at every turn. Changing the culture of a company the size of GM would be difficult under the best circumstances, but when the boss is completely in over his head it becomes a task of sysiphean futility.

Akerson’s lack of strategic vision for GM is probably best encapsulated by the unfolding mess in Europe.

With its US operations newly profitable, fixing its long-troubled European operations should have become an overriding priority for GM after its IPO, if only because every analyst cited it as cause for bearishness. Over two years after the IPO, GM’s plan for Opel (if in fact one exists) is as inscrutable as ever. Negotiations with unions are stuck on the ground floor, and while competitors like Ford are taking bold action to cut capacity, GM’s executives talk about a “product-led” Opel turnaround in a market that likely won’t ever return to past levels.

It would be bad enough if Akerson simply didn’t have a plan beyond waiting to see if Opel’s problems solve themselves, but instead he has doubled down on GM’s European problems by spending $400m on a stake in Peugeot-Citroen. That investment needs no special criticism, as about $200 million of it had to be written off after less than a year. But beyond the sheer tactical stupidity of investing in a vulnerable automaker in the midst of an industry shake-out, doubling the company’s exposure to the very problems that were plaguing Opel stands alone in terms of sheer strategic failure. Clearly Akerson missed the pre-bailout debate over a possible GM-Chrysler merger, which ended with the consensus that combining two companies with the same problems is a bad idea.

Unable to convince anyone that there is a plan to solve GM’s European mess (or that there was any logic behind the PSA alliance), Akerson has floated the notion that the French automaker will somehow help as a partner in developing markets. Beyond the fact that PSA has few accomplishments worth mentioning in developing markets (not coincidentally one of the reasons it’s in trouble), the move throws GM’s relationship with its previous developing-market partner SAIC into question. Having forged extremely tight ties with SAIC, which helped arrange a Chinese bank loan to fund its overseas operations in 2009, GM is now being led away from its Chinese ally. There might be some rationale for Akerson’s move away from SAIC if it actually made GM less dependent on its Chinese partner, but GM will continue to rely on its Chinese partner for growth in Asia and low-cost technical development. Meanwhile, the fact that one of the world’s largest automakers won’t expand into developing markets beyond China without a partner (which would eat into already-low developing market profit margins) is nothing short of baffling.

In China itself, Akerson has overseen a period of relatively strong volume growth. However, with the overall market slowing, the emphasis is moving towards the profitability of the luxury market, and here GM is losing ground to the competition. Despite its early advantage, Buick has been stuck in neutral, and Cadillac is losing relevance as German luxury brands attack the market. GM’s volume growth, on the other hand, has all come from its Wuling low-cost commercial vehicle operation, which offers only miniscule profits per vehicle. With profit opportunities few and far between in the current global climate, and blessed with a Buick brand that has been beloved in China for decades, GM could be making a lot more money in China. Adding insult to injury, GM’s aggressive joint technical development also means SAIC is already debuting technology like dual-clutch transmissions that GM doesn’t even offer in developed markets. Without brand equity now or a clear technological advantage going forward, GM’s future in China is hardly being guided with care.

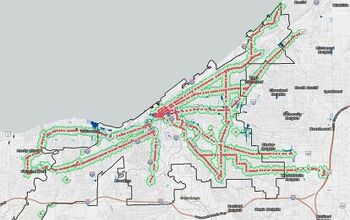

But if it’s important for GM to squeeze more profits out of China in the short term, the same is doubly true for the North America. The US market is projected to supply a huge percentage of global profits over the next several years, making it a major priority for every automaker. Thanks to the bailout, GM almost can’t help but make money in its home market, but Akerson and his team have shown no ability to lick GM’s nagging problems. Market share is not only stagnant at best, it continues to closely track incentives. Last November, GM’s incentives as a percentage of average transaction price fell below the industry average for the first time, resulting in its worst monthly market share since bankruptcy. With inventory levels remaining stubbornly high as well, it’s clear that Akerson has made no progress on any of GM’s persistent profit drags.

Worse still, Akerson’s underwhelming results in GM’s most important market are further undermined by his strategic decision to back an aggressive push into subprime lending. Having acquired Americredit, the new GM Financial has rapidly become a leader in subprime auto lending, helping GM move cars out the door but introducing new financial risks to the company. GM Financial’s default rate is pushing up, and is already higher than any other in-house lender in the business. In short, Akerson is taking GM back to the bad old days of “redlining” sales with big inventory, big discounts and subprime financing, but still can’t change the company’s momentum on market share or profitability.

For all the open wounds, impetuous alliances, self-destructive dependencies and lost opportunities scattered across GM’s global empire, the strategic mistake that underlies all of Akerson’s failures as CEO has to do with product. As a board member, Akerson was famously critical of GM’s cars; as CEO he has only hurt the product renaissance that was underway when he arrived at GM. From his well-documented decision to rush the new Malibu to market, crippling what was arguably GM’s most important car, to a signing off on a batch of too-conservative trucks, Akerson has proven repeatedly that he simply does not understand the business that he is in. And yet, despite his clear ignorance of even basic facts of the car business, he has developed a reputation for making rash decisions to “shake things up.” This fits perfectly with the pattern described in Part One of this series: Akerson is driven by ego rather than strategy.

The car business is hugely unintuitive. It looks easy, at least to the many neophytes who try their untrained hand in the field, only to go down in flames, taking investor money with them. Running a multinational car company probably is one of the most complex tasks in the world. Your research won’t bring fruits for ten years, or never, but you must spend billions on it. Your products must be right for markets and economies 5 years from now, all over the world. You are up against companies like Toyota and Volkswagen, run by CEOs who have cars in their genes, who have been around cars all their lives, and who know how to direct and lead armies of engineers, marketing and finance people into victory. The competition won’t call for Akerson’s head: The longer he is in his job, the more assured is their victory.

We were made to believe that GM was saved by the government. In reality, it was the American automobile industry that was saved from certain annihilation by foreign carmakers, and we should thank the government for it. In truly Washingtonian fashion, they win the war and lose the peace by putting the American car industry in the hands of an utter amateur. The man in charge of a car company must be a strategist and tactician of the caliber of Alexander the Great, leading from the front, knowing when to dismiss his advisers, knowing when to do the unexpected, having a sixth sense for a sudden opening in the ranks of the opposition, intuitively knowing how to ruthlessly exploit a weakness.

Akerson was put at the helm of GM by politicians who know even less about the car business than an Akerson. As the politicians sell their shares in GM and leave, they should take their man with them. If Akerson is replaced with a CEO worthy and capable of guiding GM, the stock will surely bounce, making the exit less painful.

The real tragedy of all this: the deep reserves of talented people at GM do know how to make quality products, and the company had been making real progress towards a brighter future. Now it is being wildly misled in nearly every aspect by a man who bullied his way to the top of a company he doesn’t understand in an industry that he doesn’t understand. As we will explore in Part Three of The Case Against Dan Akerson, this has led to a complete loss of confidence in the carpetbagging telecom man and his cronies, jeopardizing GM’s new lease on life. For the good of the company, it’s time to replace him with someone who understands the business… or at least understands when he doesn’t understand the business.

Previous: Breach Of Trust. Forthcoming: Part 3: Loss Of Confidence.

Editor’s note: Renaissance_Man is a nationally and internationally known industry analyst who prefers to remain anonymous

More by Renaissance_Man

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Ltcmgm78 Imagine the feeling of fulfillment he must have when he looks upon all the improvements to the Corvette over time!

- ToolGuy "The car is the eye in my head and I have never spared money on it, no less, it is not new and is over 30 years old."• Translation please?(Theories: written by AI; written by an engineer lol)

- Ltcmgm78 It depends on whether or not the union is a help or a hindrance to the manufacturer and workers. A union isn't needed if the manufacturer takes care of its workers.

- Honda1 Unions were needed back in the early days, not needed know. There are plenty of rules and regulations and government agencies that keep companies in line. It's just a money grad and nothing more. Fain is a punk!

- 1995 SC If the necessary number of employees vote to unionize then yes, they should be unionized. That's how it works.

Comments

Join the conversation

I'm very skeptical at what GM does. Not necessarily connected for that reason, but I like this story. It mentions some things that I didn't know and puts it together nicely. However I do agree with Geozinger that I don't buy it all. In my opinion this story lacks numbers to substantiate the story. I expect something more from "a nationally and internationally known industry analyst who prefers to remain anonymous". In it's current form this article looks more like an extended comment made by a regular TTAC visitor. Only this time he took an some more time to write it down in a nicer way than he would with his regular comment.

Some decent points. On AmeriCredit/GM Financial, saying that they have too much sub-prime market share shows that this guy is clearly not a financial analyst. they bought the leading subprime leader. of course they have higher subprime market share than other Captives. but who would you rather have make subprime loans? Guys that just rotated out of the OEM marketing dept or people that have spend their lives in subprime lending?