My Role In The Extinction Of The American Muscle Car

1969 Chevelle SS

A few weeks a go I had the opportunity to watch part of the Barrett Jackson auction. I found myself captivated by the colorful commentary that went along with each sale. Every car had a story and the commentators spent a great deal of time telling us about them. They also discussed the cars’ performance, available options and recited the original production numbers, contrasted by telling us exactly how many of those cars survive today. It turns out that many of the cars I regularly used to see back in the 1970s are extremely rare today. I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised, however, after all, I had a hand in making them go away.

By the time the 1980s got into full swing, around 1983, people were good and tired of the 1970s. The ‘70s had been pretty rough on the average American. We had our pride hurt when Saigon fell, we lost faith in our political institutions thanks to Watergate and we were embarrassed when our embassy was stormed by a bunch of kids in Iran. To make matters worse, we had gone way overboard on cheesy variety shows, bell bottoms and the cocaine and now we had one hell of a hangover. It was, we collectively decided, better if we just put the past behind us.

In 1983 I was a junior in high school and, with the economy still in a shambles, jobs in small-town America for kids my age were few and far between. Fortunately, my mom and dad weren’t stingy and I had enough money in my pocket to play Defender at the 7-11 and to put gas in my 6 cylinder Nova, but I aspired to bigger things. I wanted to build a fast car. It was my search for a job and my attempt to access to cheap parts that led me to form a friendship with the local hot-rodder.

Already married with three kids, Tim Harris was only about a decade older than me. He was the kind of guy who lived and breathed cars; the kind of guy who forever smelled of old crankcase oil and Dexron II. As a neighbor, he drove down your property values. His yard was filled with half stripped cars, disembodied engine and racks of body parts. Naturally, I thought he was the coolest guy around.

Easy Prey

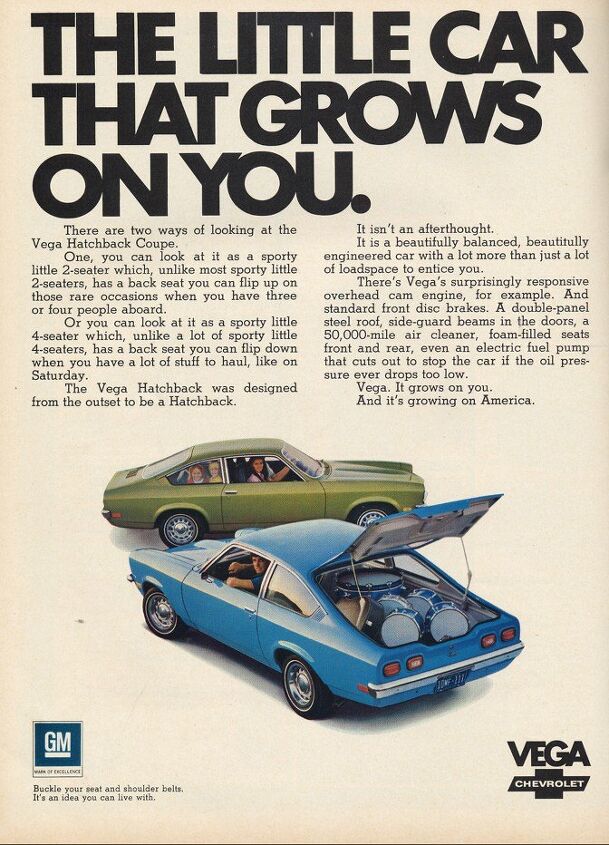

The owner of several Chevrolet Vegas in his younger years, Tim had begun collecting parts to keep his own cars running but soon found that people were willing to pay a handsome premium for the parts they needed to keep their own cars going as well. Before long, Tim had an established business, buying up and parting out Chevrolets all over the county and, luckily for me, his business had grown to the point that he needed someone to help him. Since I was willing to work for a pittance, and bought most of my parts from him anyway, I got the job.

Tim had me do all sorts of work around the his house. I hauled wood, dug ditches, ran barbed wire and helped dismantle the cars he brought home. He worked me hard, but sometimes I got to ride along as Tim went to pick up one junker or another and, as we drove, he taught me the tricks of his trade. Like most money making ventures, the underlying idea was simple, the execution was not.

The process began in the driver’s seat and we drove about ceaselessly scouring the area for possible purchases. A potential buy was always a car that was sitting. Signs of a sitting car included a layer of dirt, pine needles or leaves on top and a patch of longish grass or other debris underneath. Flat tires were almost always good for us while an open hood or ongoing body work were usually not. With the economy in a protracted slump and high gas prices at the pump, that part was easy.

It took real skill, however, to know what you were actually looking at. I have, it turns out, a photographic memory and I soon developed an encyclopedic knowledge of the cars of the 60s and 70s. I knew their shapes, options, trim levels, possible power trains, even more esoteric things like whether or not they might be hiding disc brakes under their hubcaps. I could look at a car from the seat of the van and instantly report what it was. Tim would do the other important part, the mental math that told him just how much profit our find might actually bring. If a car was worth it, we knocked on the door of the house.

This system worked surprisingly well. Tim was a cash buyer and a great many people were swayed by the sight of his money. Together we purchased some of the great cars of the era.

One that should have been allowed to escape.

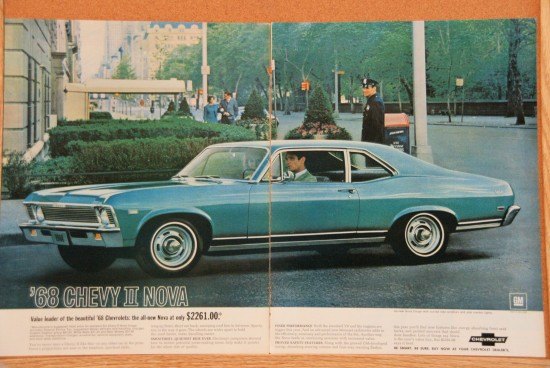

At one house, Tim scored a 1968 Chevy II with a 250 HP 327, a Muncie 4 speed and a positraction rear end for $300. It had been sitting for a while, but together Tim and I compression started the engine by rolling it down a small hill. The old car fired up and ran strong. I laid a great deal of rubber at every stop on the way home. Naturally, I was in love and wanted to save the baby blue car, but Tim would have none if it. In less than a month every part of value was sold and Tim and I hauled the stripped carcass to the recyclers in order to make room for the next victim.

So it went with dozens of cars and Novas, Camaros, Chevelles, Impalas and dozens upon dozens of late 60s Chevy trucks were sacrificed one piece at a time to the great god of commerce. Like a 19th century whaling operation, we stalked our prey, made the kill and then hauled the beast ashore where we stripped away every usable bit one piece at a time before taking the final remains to a place where they were rendered down into smelter fodder. There was one exception.

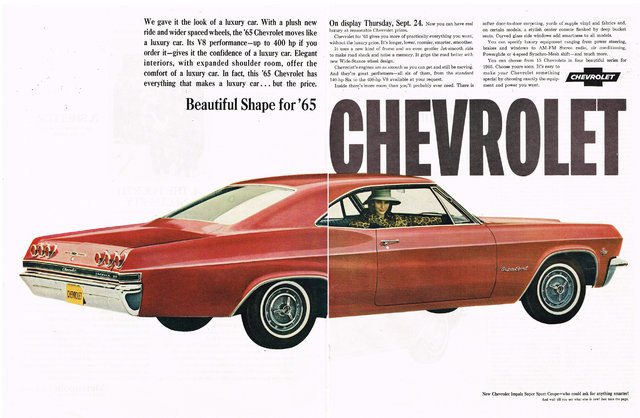

One that did get away.

The 1965 Impala SS 396 was truly a thing of beauty. Canary yellow with a black vinyl top, we found her on four flat tires and with a surprising amount of moss on the cement slab beneath her. I could see the cold calculation in Tim’s eyes as we walked around the dignified old girl, big block engine, SS wheel covers, disc brakes, all the trim pieces in good condition, flawless interior. This car was ripe for the picking. Tim ended up paying just $500 to an elderly lady who confessed she just wanted to be rid of it.

Once the title was in hand, we spent a few minutes getting the car prepped for the trip home. I pumped up the tires with a small compressor, checked the oil and water, and then we started the old big block using jumper cables. It ran rough at first but soon settled down and when we were ready, Tim let me go ahead while he followed in the van.

The old car was nice inside and the big engine ran well. The transmission shifted smoothly, and not for the first time I noticed what a really fine car it was. It did seem to wander around a bit out on the road and it had a fair amount of play in its steering, but old Impalas, especially big block cars, had a tendency to wear out suspension bushings. It was a minor problem, and I made the trip home without incident.

After parking the car, I got out and gave it a good serious look. I was still there when Tim pulled up a minute later. “This is a nice car.” I said.

“Yeah,” answered Tim, “A really nice car.”

“You think maybe someone would just buy the whole thing?” I asked.

“I could get more from parts than I could the whole thing.” Tim replied.

“It wouldn’t be right though.” I said.

‘I know.” Said Tim, “I know.”

The next week Tim put an ad in the paper and an elderly gentleman made the trip out to where we lived in the country to buy the car. Tim got $900 for it and seemed happy enough as the old car rolled down the driveway and away into the afternoon. But as it faded into the distance, he turned on me, “I could have made more money if I hadn’t listened to you.” he said accusingly.

“Somebody has to be your conscience.” I answered.

His expression lightened and he smiled. “I know.” said Tim heading for his van. “Come on, let’s go find something else we can make money on.” I paused a moment, then laughed and went with him, always ready to drive home another piece of history.

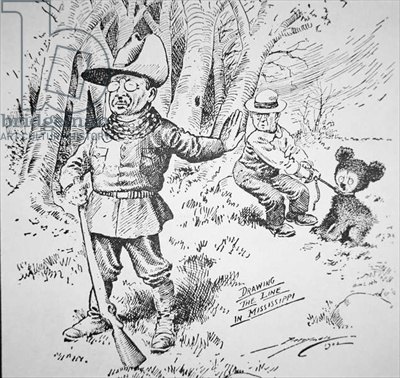

Teddy Roosevelt refusing to kill a captive bear.

Thomas Kreutzer currently lives in Buffalo, New York with his wife and three children but has spent most of his adult life overseas. He has lived in Japan for 9 years, Jamaica for 2 and spent almost 5 years as a US Merchant Mariner serving primarily in the Pacific. A long time auto and motorcycle enthusiast he has pursued his hobbies whenever possible. He also enjoys writing and public speaking where, according to his wife, his favorite subject is himself.

More by Thomas Kreutzer

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Carson D I thought that this was going to be a comparison of BFGoodrich's different truck tires.

- Tassos Jong-iL North Korea is saving pokemon cards and amibos to buy GM in 10 years, we hope.

- Formula m Same as Ford, withholding billions in development because they want to rearrange the furniture.

- EV-Guy I would care more about the Detroit downtown core. Who else would possibly be able to occupy this space? GM bought this complex - correct? If they can't fill it, how do they find tenants that can? Is the plan to just tear it down and sell to developers?

- EBFlex Demand is so high for EVs they are having to lay people off. Layoffs are the ultimate sign of an rapidly expanding market.

Comments

Join the conversation

Assuage your guilt! Nowhere near as many of these cars disappeared this was as did through the efforts of the tin worm. Nowhere near.

Lovely story. Great read. Sad how all those cars are gone, but really... time and rust would have done many of the worse ones in, eventually.