Avoidable Contact: Who Wants to Last Forever?

It was a sunny day in 1994 when I fired up my 1990 Volkswagen Fox and took my newly acquired “Swedish Mauser” 6.5×55 rifle to the local range. At that point in time, the rifle was around eighty-two years old, having been manufactured at some point in 1912. It worked fine and was accurate to slightly under one inch at one hundred yards — the so-called “minute of angle” which is a basic standard of accuracy for long guns. Having satisfied myself that this time-worn gun was up to snuff, I went home and played some guitar. In this case, the guitar was my 1982 Electra Phoenix X130, already twelve years old but showing very little wear despite a harrowing four years following me around a college campus.

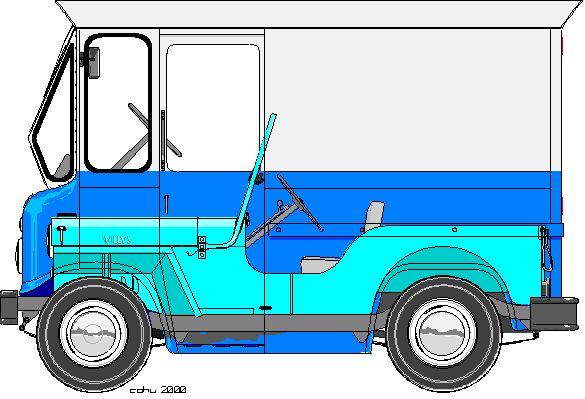

My mail had been delivered that day by a mailman driving a Grumman LLV, very similar to the one pictured at the top of this column. And although I didn’t know it, Porsche was less than three months away from building a certain white 1995 993 Carrera with factory-matched white wheels.

Approximately eighteen years later, my Mauser is doing fine service for another shooter, who reports that it has required no repair or maintenance beyond the basics. It will celebrate its hundredth birthday some time this year. My Electra rarely comes out of its case any more, but when I do play it there’s no evidence that it’s now a thirty-one-year-old guitar. My mail was delivered today by a mail lady in a Grumman LLV which could not have been manufactured any fewer than fourteen years ago. And my 1995 Porsche 993 Carrera slumbers in the cold garage dreaming of spring, shiny and corrosion-free.

The 1990 Fox I drove to the range that long-ago day? Gone, junked, rusted out, driven into the ground. In a story full of what they call “durable goods”, the Fox wasn’t truly durable at all. It was used and discarded, probably utterly worthless by the time the odometer reached the 150,000 mark. Surely VW understood how to make a consumer product as durable as a wooden Japanese guitar or a ninety-year-old rifle. The industry as a whole understood how to make durable items. My little white 993 still runs. The local mail truck still runs, although we’ll discuss later why Grumman’s understanding of “durable” differs from Porsche’s. The Fox’s lack of durability was almost certainly due to a particular decision or series of decisions made somewhere at Volkswagen. Why? What is the advantage of deliberately creating less-than-durable products? Put another way — why aren’t all vehicles “long life vehicles”?

The air-cooled Porsche 911 was a durable good in one sense of the term: a fundamentally sound, expensively engineered vehicle using high-quality components that required specialized maintenance to last nearly forever.

I’ve been fascinated lately by the story of the US Postal Service and its efforts to obtain and use “long life vehicles”. You can read a fair amount of the LLV’s history at LLV.com. The original Sixties Jeep stepvans were rather intelligent attempts to marry a World War II-proven mechanical platform with a much more spacious interior.

The resulting packaging is very efficient and well-adapted to any relatively low-speed motoring application where aerodynamic drag isn’t an issue. Since postal delivery tends to be one of those low-speed applications, the Postal Service was quite interested in the little vans. There was just one problem: they weren’t quite big enough. Enter the LLV.

The Grumman LLV takes the stepvan concept, adds aerospace-style riveted construction, and plops the whole thing on the simplest platform General Motors could muster — that of the S-10 pickup. The intent was to create a vehicle with a long life. Duh. It’s called the “Long Life Vehicle.” But what does that mean?

I’ve identified three basic approaches to creating durable vehicles. The first one we’ll call the aircooled-Porsche approach. Aircooled Porsches were built to exacting tolerances from expensive materials. Starting in the mid-Seventies, they were galvanized to prevent corrosion. The basic guts of a 911 should last a million miles. You may have to replace some relays, redye the leather, or rebuild the engine, but the basics of the car are high-quality and durable. If you want to drive your 911 until the odometer turns over, you can do it — but it will cost you.

Some of the iconic Japanese cars of the Eighties, such as the Civic and Corolla, were built using a different approach. They were what Toyota now calls “fat product” cars — vehicles built to be just a little better than they really needed to be. The engineering of these cars was very thorough, money was spent where it needed to be spent to ensure mechanical reliability, and as a result you can drive a 1989 Honda Civic a very long time. Eventually, you will fall prey to the relatively low cost of the materials used in said Honda Civic. The body will rust or corrode. The engine will wear out and will not accept another rebuild. A Civic won’t last as long as a 911, but it won’t cost you nearly as much time or effort to keep it running during its lifetime.

Grumman chose a third way. The Chevrolet S-10 and its 2.5L “Iron Duke” engine were known, even then, to be pretty low-quality items. The advantage in using those low-quality items came in ease and cost of service and parts replacement. It takes less mechanical aptitude to service an LLV than it does to service a Corolla or Porsche. In fact, it’s my understanding that the Postal Service sometimes trains its own mechanics, just like the Army does. To be geeky about it, the set of all techniques and knowledge required to maintain an LLV is a subset of the set of all techniques and knowledge required to maintain modern passenger vehicles, and a small subset at that.

The LLV body itself appears to be almost maintenance-free. It’s aluminum, riveted like an aircraft body and just as weather-resistant. Most of the LLVs I see continue to look pretty decent. The bumpers are large, strong, utterly repulsive-looking black rubber affairs. The homeowners in my neighborhood rush home early every Thursday to get their trash cans out of the street before the postal workers clock ‘em out of the way with their big LLV bumpers. I’ve personally seen a large steel trash can fly nearly twenty feet after being struck by a speeding LLV, with no visible damage whatsoever to the aforementioned stepvan. Don’t try this with your Lamborghini Valentino Balboni LP550-2.

Come to think of it, I’ve seen all sorts of abuse heaped on LLVs by postal workers, and rarely do the LLVs complain. They catch fire sometimes (apparently some shortcuts were taken in Grumman’s wiring, so to speak) and I wouldn’t want to crash one into anything more substantial than a steel trash can, but in general these are hard-working, reliable, abuse-resistant vehicles. The Postal Service seems to agree. Nominally speaking, the LLV will eventually be replaced by the larger, more sophisticated Ford CRV in both gasoline and electric variants. In practice, the LLVs are being refurbished and extended at least to the end of this young decade. It’s not unlikely that the existing LLV chassis will survive, perhaps with replacement electric or hybrid powertrains, well into the 2030s.

What we have with the Grumman LLV, then, is a vehicle which can last twenty-five years or longer with relatively unskilled maintenance. It uses inexpensive parts. It has plenty of space. With something besides an Iron Duke ahead of the firewall, it would probably even get decent gas mileage. I would ask “Why isn’t there a civilian version?” but the quickie answers to that — crash safety, uggo bumpers, hurricane-force highway wind noise — are too easy to produce.

Instead, let’s ask this question: We have cars on the market that are sold on safety. We have cars on the market which are sold on performance. We have cars on the market which are sold on price, perceived reliability, environmental impact, cupholder count, faux-coupe silhouette, you name it. There’s a car out there catering to nearly every possible desire, from the ridiculous to the sublime… except long-term durability. Isn’t there anybody out there who wants a long-life vehicle of their own?

It wouldn’t have to be a riveted-aluminum box. It could be a sedan, wagon, or sports car. Nor would it have to miserable to operate. There is plenty of well-understood and time-tested convenience equipment out there. Many existing suppliers understand very well what’s required to significantly increase the life of their products; somebody would just have to be willing to pay the extra cost.

What would that cost be? I can’t believe that it would be double the cost of existing vehicles. If a Honda Civic can be profitably sold at $17,000, a long-life version almost certainly wouldn’t cost $34,000. Perhaps there would be a 50% markup. I’m not convinced it would cost any more than the addition of a hybrid powertrain. Let’s dream up a long-life Civic real quick: a plain 1.6 SOHC sixteen-valve engine, with high-strength steel and hardened components. Five-speed manual transmission. Simplified electronics, with upgraded connectors and sensors. Steel wheels. Galvanized body. High-strength fabric interior. A simplified dashboard with access panels to reach the components within. Thicker body panels that are bolted, rather than plastic-riveted, to the frame rails. The list goes on. The million-mile Civic could probably be engineered and built without too much difficulty. It’s certainly a simpler item than an Acura ZDX.

Unfortunately, I’m not sure it would be any more popular than that rather beaky-looking awkward-mobile. The Element hasn’t set any sales records, and that’s probably the closest thing on the market to a deliberately simplified, utilitarian production vehicle. It would be hard to explain to new-car buyers why they should pay more for a vehicle that they probably won’t keep more than a few years. While the resale value of long-life Civics would be high, Honda might not appreciate having to compete with its own products for thirty years. Why buy a new “LLC” when used ones are, literally, just as good? It’s the same problem that haunts companies like Glock and Gibson: when your old stuff doesn’t wear out, the new stuff doesn’t always fly off the shelves.

It’s difficult to imagine that Honda would embrace a Long Life Civic, particularly not when every new Honda bears conspicuous evidence of cost-cutting. Toyota is currently facing a tsunami of trouble based on its decision to save money on gas pedals and electronics (Written before the real tsunami — JB), but I wouldn’t look for their pendulum to swing back to the 1990 Corolla any time soon. Porsche and Mercedes-Benz have learned the hard way that snazzy features and hard-sell marketing move more iron than evergreen aircooled Carreras or million-mile W123 sedans. There doesn’t seem to be any room in the market for a product sold on the basis of reliability.

Except. There’s a company that has a bit of a financial advantage at the moment, some momentum, and engineering prowess to spare. They really need the PR boost and public image buffing that could come from deliberately making long-life vehicles, and they know how it was done before. Ladies and gentlemen, I propose… The Grumman/General Motors Long Life Cruze. Enjoy a million miles behind the wheel of your stylish little sedan! Embrace simplicity and try the locally produced Long Life Cruze! Forget the vagaries of fashion by driving a car that already looks like it was styled a decade ago! Surround yourself with a Korean-designed interior that will outlive the next dictator of North Korea!

It’s a dumb idea, but it’s not as stupid as the Chevy Volt Dance.

More by Jack Baruth

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Arthur Dailey The longest we have ever kept a car was 13 years for a Kia Rondo. Only ever had to perform routine 'wear and tear' maintenance. Brake jobs, tire replacements, fluids replacements (per mfg specs), battery replacement, etc. All in all it was an entirely positive ownership experience. The worst ownership experiences from oldest to newest were Ford, Chrysler and Hyundai.Neutral regarding GM, Honda, Nissan (two good, one not so good) and VW (3 good and 1 terrible). Experiences with other manufacturers were all too short to objectively comment on.

- MaintenanceCosts Two-speed transfer case and lockable differentials are essential for getting over the curb in Beverly Hills to park on the sidewalk.

- MaintenanceCosts I don't think any other OEM is dumb enough to market the system as "Full Self-Driving," and if it's presented as a competitor to SuperCruise or the like it's OK.

- Oberkanone Tesla license their skateboard platforms to other manufacturers. Great. Better yet, Tesla manufacture and sell the platforms and auto manufacturers manufacture the body and interiors. Fantastic.

- ToolGuy As of right now, Tesla is convinced that their old approach to FSD doesn't work, and that their new approach to FSD will work. I ain't saying I agree or disagree, just telling you where they are.

Comments

Join the conversation

actually many of the LLV's are on S10 chassis. Morgan Olson was looking into sourcing the frame rails for service parts bit the deal fell through. Take awhile for a S10 rail to rust through.

My old BMWs require several "special" tools. For most, however, a 2 lb hammer is a good substitute. A major benefit from DIYing is that you can fit it into your schedule easier than the having to deal with a mechanic's schedule. BTW, I installed my first radiator at 9 yrs old. I am by no means a gifted mechanic. Every bit of expertise was gained at the cost of skinned knuckles and one mistake at a time. My 528e was the first EFI engine. I hung back with with carbed engines due to mistrusting the new technology. The Bosch fuel injection is so much better than a carb. A Bentley manual and a volt/ohm meter is all you need to trouble shoot it. So far, all I have needed to replace were a set of injectors.