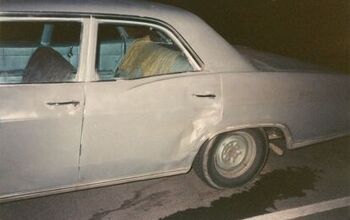

1965 Impala Hell Project, Part 20: The End

More than a month has passed since Part 19 of the Impala Hell Project series, partly because I’ve been getting sliced up by sadistic doctors and flying on Elvis-grade prescription goofballs but mostly because the final chapter has been so difficult to write. Here goes!

By the year 2000, I’d accomplished most of what I’d set out to do with the Impala Hell Project. I’d started as a stone-broke performance/installation artist with an ambitious vision of a real art car, to show that the artist who works with the automobile as a medium isn’t required to disrespect the canvas.

I never lost touch with that vision, even as I turned the car into a bulletproof daily driver and traveled California looking for slacker thrills in it.

As I matured, the Impala stayed with me. It moved me and all my possessions from San Francisco to Atlanta, then served as my foot in the door for my first automotive writing job.

In my 30s and finally having achieved a toehold in the middle class, I built a potent 400-cubic-inch small-block to replace the 350 I’d installed in 1990. My goal was to get the car to break the 14-second barrier at the dragstrip, and I succeeded in the summer of 1999: 13.67 seconds.

Then I found myself asking Now what? I hadn’t used the Impala as a daily driver since I’d discovered the quick, reliable, gas-sipping ’84-87 Honda Civic/CRX upon my return to California in 1996, and having two or three Civics plus a big, seldom-driven Detroit monster was proving to be a real parking headache in my crypto-urban neighborhood on the Island That Rust Forgot.

No car had ever held such emotional significance to me, and I felt certain that no future car ever would come close. I’d put more creative energy and sheer work time into the Impala Hell Project than I had for any project I’d ever worked on… and I was beginning to recognize that as a problem for a man who really wanted to put those creative energies into fiction writing. I was pushing 35 and feeling increasingly chained to a 3,500-pound link to my lifetime-ago early 20s.

Having moved 13 times during the decade of the 1990s, I’d gradually learned to pare down the possessions in my life to the bare minimum. Tools, sure, keep ’em… but after having packed, lifted, and unpacked all my crap all those times I’d developed a horror at anything that resembled hoarding of possessions for sentimentality’s sake. But the Impala was special. Surely I could start a new project with it, maybe make it into a road racer, or an electric car, or… something. For the time being, I avoided any decision with the Impala, moving it enough to keep ahead of street-sweeping tickets and driving it to work every few weeks.

Then I dove headlong into a real Hell Project: a 900-square-foot cottage on Alameda’s main downtown drag, built sometime between the Gold Rush and the late 1870s. A seriously cool structure, built of massive hand-hewn redwood beams and sweating Bay Area history, but battered by 140 years of hack-job repairs by cheap-ass absentee landlords. My new house had just two off-street parking spaces, accessible down an easement-ized driveway on the next block over (though a third car could be made to fit, barely, provided it was an Austin-Healey Sprite). Now all my spare time was being taken up with carpentry and wiring and plumbing, I still wasn’t advancing my fiction-writing skills, and the Impala was just sitting there as a sort of souvenir of the previous ten years of my life. The dilemma!

My friend and future 24 Hours of LeMons teammate Dave Schaible, who went on to create the incredible Model T GT, had given me a lot of very useful advice about building the Impala’s new engine, and he was always building some street rod project or other in his shop. I knew he had a ’32 Ford in the works, and that he’d been so impressed by the performance of the Impala’s engine that he wanted to build one just like it.

I decided to cast the die. I made an ironclad resolution: No more fun car projects until I write and sell a novel! I meant it, too; to rip off my favorite Knut Hamsun phrase, my eyes were like two knife points. I was as serious as an Old Testament prophet on the subject. There was no way I’d be able to sell the Impala to anyone who would keep driving it; it had a lot of good parts, but the battered shell of an incredibly plentiful mid-60s full-size Chevy was essentially scrap metal. None of my hipster friends wanted anything to do with the car (such would not be the case today, what with all the 24 Hours of LeMons freaks who groove on this sort of absurd machinery), so I called up Dave and offered him the whole mess for not much more than the money I had in the engine. “I’ll take it!” he said.

Dave pulled the engine, the Powertrax locker differential, and a few more bits and pieces.

The 406 got a paint-and-chrome job and looked great in the ’32. I never rode in this car, but I assume it was a handful with that uncivilized, lumpy-cammed engine in place.

I was too heartbroken to ask what happened to the rest of the Impala for a few years. Later, I found that Dave sold the shell to a guy in Hayward with a shop specializing in Impala lowriders. I’d like to think that some pieces of my car now live on in a candy-apple-red Impala coupe with hydraulics and a mural depicting an Aztec sacrifice.

Starting that day, my only car projects were those that made money— no fun projects until I sold a novel, remember? I’d go to the San Francisco towed-car auctions, located at Pier 70 (not far from my dot-com tech-writing job) every month or so and buy Tercels, Civics, or Sentras for $100 each. I’d sell whatever stuff remained in the trunks after getting picked over by the tow-truck drivers (one time I got a few hundred bucks for a bunch of water-ski gear I found in a Sentra’s trunk), fix whatever needed fixing, and turn the car around for a grand or so.

Then, between software jobs in 2004, I got a call from a friend-of-a-friend in London who worked as an editor for the “erotic fiction” division of Virgin Books. He’d pay me good money, in genuine pounds sterling, for 70,000 words of high-class smut, he said. I did it, the book sold 5,000 copies (and still sells today, as a Kindle edition), and I got paid. The smut scenes were nothing special— what can any writer do with a schtup scene that hasn’t already been done ten thousand times?— but I remain proud of parts of the novel. So proud, in fact, that I’ve created a quasi-de-pornified, still-probably-not-quite-safe-for-work excerpt for your reading enjoyment (PDF). Crafting a novel, even in such a disreputable genre, gave a much-needed boost to my writing skills and confidence, so the “no more fun car projects” vow I’d made was worth it. On a related note, the pseudonym I used for Torment, Incorporated turned out to be quite useful; here is the entire complicated story of How I Got This Silly Name.

Of course, selling that novel meant that I could resume wasting time on fun car projects; the first one was the Black Metal V8olvo 24 Hours of LeMons car in 2008, followed by the 20R Sprite Hell Project, the Dodge A100 Hell Project, and whatever I buy next; right now, I’m torn between a Leyland P76, an early Toyota Century, a ZAZ-968, and a ’71 Chrysler Newport coupe with 6-71 blower and manual transmission. Do I wish I still had the Impala? Yes, every day. Am I glad that I forced myself to write that first novel? Yes, every day. The next Murilee Martin novel is in the works for 2012, by the way.

Murilee Martin is the pen name of Phil Greden, a writer who has lived in Minnesota, California, Georgia and (now) Colorado. He has toiled at copywriting, technical writing, junkmail writing, fiction writing and now automotive writing. He has owned many terrible vehicles and some good ones. He spends a great deal of time in self-service junkyards. These days, he writes for publications including Autoweek, Autoblog, Hagerty, The Truth About Cars and Capital One.

More by Murilee Martin

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Arthur Dailey We have a lease coming due in October and no intention of buying the vehicle when the lease is up.Trying to decide on a replacement vehicle our preferences are the Maverick, Subaru Forester and Mazda CX-5 or CX-30.Unfortunately both the Maverick and Subaru are thin on the ground. Would prefer a Maverick with the hybrid, but the wife has 2 'must haves' those being heated seats and blind spot monitoring. That requires a factory order on the Maverick bringing Canadian price in the mid $40k range, and a delivery time of TBD. For the Subaru it looks like we would have to go up 2 trim levels to get those and that also puts it into the mid $40k range.Therefore are contemplating take another 2 or 3 year lease. Hoping that vehicle supply and prices stabilize and purchasing a hybrid or electric when that lease expires. By then we will both be retired, so that vehicle could be a 'forever car'. Any recommendations would be welcomed.

- Eric Wait! They're moving? Mexico??!!

- GrumpyOldMan All modern road vehicles have tachometers in RPM X 1000. I've often wondered if that is a nanny-state regulation to prevent drivers from confusing it with the speedometer. If so, the Ford retro gauges would appear to be illegal.

- Theflyersfan Matthew...read my mind. Those old Probe digital gauges were the best 80s digital gauges out there! (Maybe the first C4 Corvettes would match it...and then the strange Subaru XT ones - OK, the 80s had some interesting digital clusters!) I understand the "why simulate real gauges instead of installing real ones?" argument and it makes sense. On the other hand, with the total onslaught of driver's aid and information now, these screens make sense as all of that info isn't crammed into a small digital cluster between the speedo and tach. If only automakers found a way to get over the fallen over Monolith stuck on the dash design motif. Ultra low effort there guys. And I would have loved to have seen a retro-Mustang, especially Fox body, have an engine that could rev out to 8,000 rpms! You'd likely be picking out metal fragments from pretty much everywhere all weekend long.

- Analoggrotto What the hell kind of news is this?

Comments

Join the conversation

Nice ! . I'm an old geezer journeyman mechanic but I too , really like your writing style . I hope to find links to the A-100 stories . -Nate

I found this series a few hours ago.I read it from parts 1-20 in one sitting. Enjoyed the journey! Thanks Murilee! J.S.