Fuel Economy: It's Your Problem Too

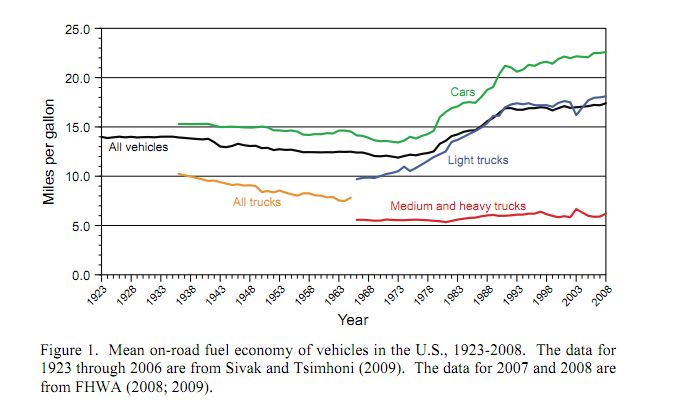

A University of Michigan study [ PDF] shows that, in the 85 years between 1923 and 2008, average on-road fuel economy in the US has improved a mere 3.5 MPG. In fact, the study shows that driving a car is even more energy-intensive (per occupant-mile) than flying on an airplane (3,501 BTU per mile versus 2,931 BTU per mile). Some will blame weak government regulations for this unimpressive result, but the study found that the convenient government scapegoat is not completely to blame.

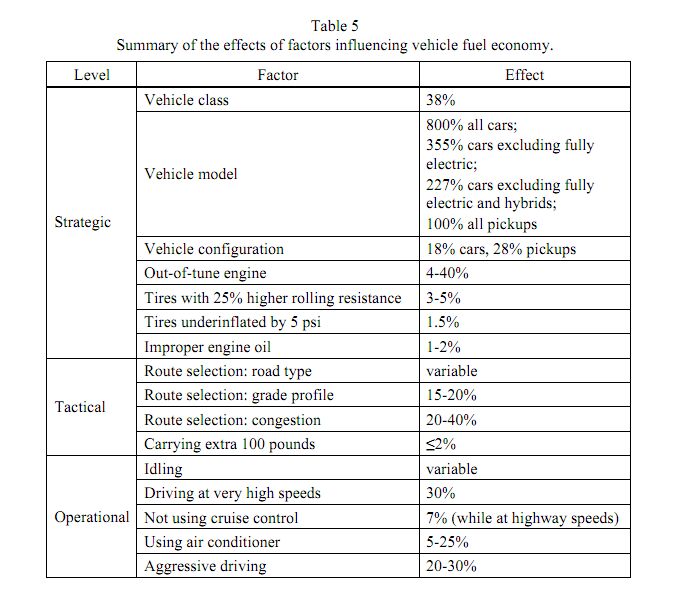

This report presents information about the effects of decisions that a driver can make to influence on-road fuel economy of light-duty vehicles. These include strategic decisions (vehicle selection and maintenance), tactical decisions (route selection and vehicle load), and operational decisions (driver behavior).

The results indicate that vehicle selection has by far the most dominant effect: The best vehicle currently available for sale in the U.S. is nine times more fuel efficient than the worst vehicle. Nevertheless, the remaining factors that a driver has control over can contribute, in total, to about a 45% reduction in the on-road fuel economy per driver—a magnitude well worth emphasizing. Furthermore, increased efforts should also be directed at increasing vehicle occupancy, which has dropped by 30% from 1960. That drop, by itself, increased the energy intensity of driving per occupant by about 30%

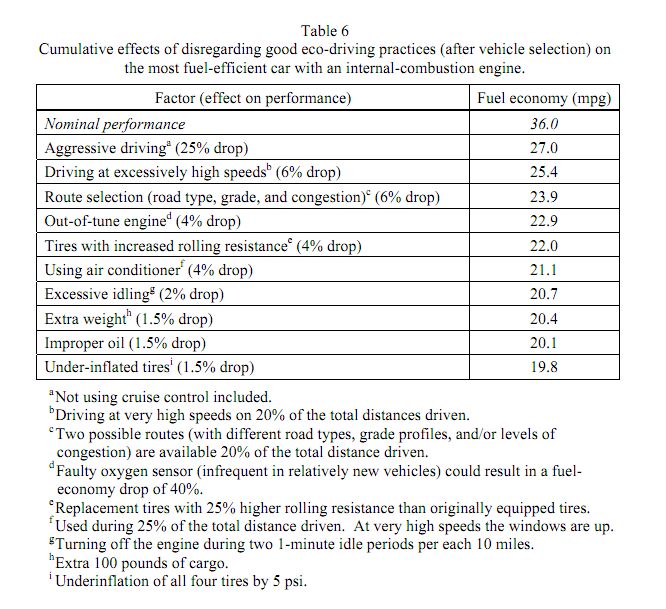

So, the industry (and its government regulators) still have a huge impact on overall on-road fuel economy, as there is still a major swing between the most and the least fuel-efficient car. But, as the chart above shows, even if you do pick an efficient vehicle (36 MPG in this example), it’s still possible to operate it at a serious penalty to fuel economy. According to the report, consumers have the power to cut emissions by a much as 45% by paying closer attention to the following issues:

Maintenance: Keeping your engine tuned, using fuel-efficient tires, and using low-friction engine oils.

Route selection: Maximizing highway use, optimizing the route’s grade/elevation profile, avoiding traffic

Driving techniques: Minimizing idle time, minimizing engine revolutions, using cruise control, minimizing a/c use, and driving less aggressively

And this emphasis on personal responsibility for fuel economy even touches lifestyle choices you never associated with driving. For example, the study notes

the average adult in the U.S. in 2002 was about 24 pounds heavier than in 1960 (Ogden, Fryar, Carroll, and Flegel, 2004). This weight gain results in a reduction in fuel economy of up to about 0.5%.

In other words, fuel economy as a holistic goal is a partnership between the industry and consumers. After all, even if the government mandates super-high fuel economy standards, it’s still up to consumers to operate their vehicles such that they actually achieve their promised efficiency. The power is in our hands to ruin our own fuel economy by as much as 45%, whether we drive a fuel-sipping subcompact or a gas-guzzling pickup. The only problem is that consumers no more want to drive super-efficiently than manufacturers want to make super-efficient cars. But sooner or later, something’s got to give… especially since on-road fuel economy has improved by .04 MPG per year since 1923.

More by Edward Niedermeyer

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Carson D I thought that this was going to be a comparison of BFGoodrich's different truck tires.

- Tassos Jong-iL North Korea is saving pokemon cards and amibos to buy GM in 10 years, we hope.

- Formula m Same as Ford, withholding billions in development because they want to rearrange the furniture.

- EV-Guy I would care more about the Detroit downtown core. Who else would possibly be able to occupy this space? GM bought this complex - correct? If they can't fill it, how do they find tenants that can? Is the plan to just tear it down and sell to developers?

- EBFlex Demand is so high for EVs they are having to lay people off. Layoffs are the ultimate sign of an rapidly expanding market.

Comments

Join the conversation

There's another aspect that hasn't really been discussed that I feel makes the quote "… especially since on-road fuel economy has improved by .04 MPG per year since 1923" misleading... If you look at the graph the category of 'medium and heavy trucks' only enters the picture in the mid-60's. Their 6 MPG average, combined with how much they get used today, means they really drag down the collective average, yet I'm sure no one here would want to get rid of them and rely on freight trains to get cargo everywhere. In a society where stuff needs to get transported as fast as possible there's no getting around their use, and I'd be interested in an average that does not take into account this category for a more realistic picture of how much personal cars have improved.

Not mentioned in the article (but highlighted in the comments): Where to live & work. I live in the suburbs; I work in the suburbs. My commute is thus very short--probably half of the typical length. Such a commute therefore cuts my gas (and other products, e.g., tires, oil changes) consumption proportionately. Another hidden benefit to short commutes: Reduced interaction between cars (traffic). Since I drive only a short distance, I never get on most of the roads that others use, so I never get in their way. If others do the same, they never get in my way. I suspect that when the math is worked out, there is a factoral relationship (increases faster than exponential) between miles driven & amount of traffic. Thus, even a small overall decrease in everyone's commute would make a significant difference in everyone's efficiency, time, & stress.