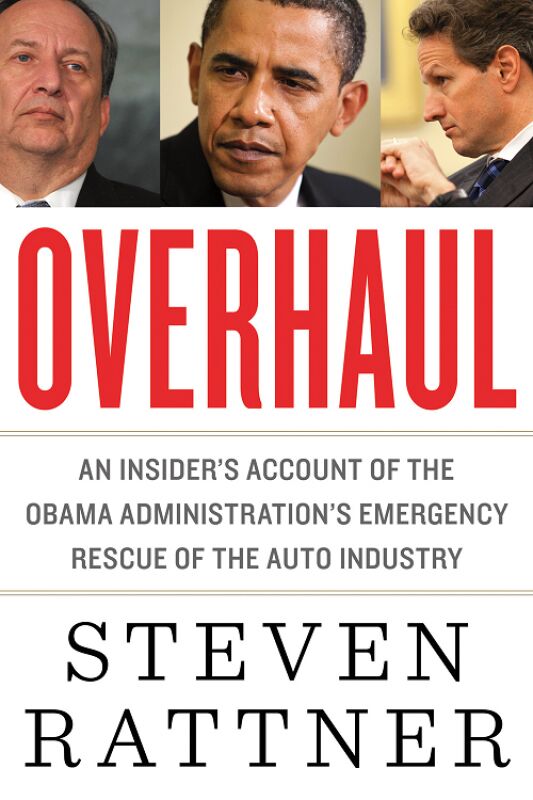

Book Review: Overhaul: An Insider's Account of the Obama Administration's Emergency Rescue of the Auto Industry

John McElroy recently quit the Automotive Press Association because they invited Steven Rattner, former head of the government’s auto industry task force, to speak. He warned, “If you want to read [his] book, DON’T BUY IT. Get it from your local library, because Steven Rattner is a rat who doesn’t deserve a dime of anyone’s money.” What he didn’t say: don’t read the book. And with good reason: it’s well-written, insightful, and definitely worth reading.

McElroy has repeatedly attacked Rattner’s character, even ripping on his last name, Fast Times at Ridgemont High style. He notes that Rattner was an investor in Cerberus before serving on the task force, likely used his influence to keep the media from covering his wife’s DUI, and was involved in a kickback scheme with the New York pension fund. I don’t doubt that this is all true, but still see insufficient grounds for such a vehement reaction.

Rattner’s book clearly involved a lot of hard work. He did not simply write up his own recollections. Instead, he claims to have interviewed many of the people involved, and impressive levels of detail and accuracy confirm this. The average book by a seasoned automotive journalist is shoddy in comparison.

If anyone should see a thoroughly researched book as work that deserves to be compensated, it is a journalist. Essentially, McElroy is arguing that anyone accused of a crime (Rattner hasn’t actually been convicted of a crime, though he has now paid very large settlements) does not deserve to be compensated for any of their work, even hard work unrelated to the crime. (A book based on the kickback scheme would be a different matter.)

This isn’t a tenable position. Something else is going on. McElroy provides some hints, labeling the book a “kiss and tell.” He’d clearly prefer that Rattner had, like most insiders, kept his mouth shut. The problem isn’t the accuracy of what Rattner wrote. This isn’t questioned. The problem is that Rattner divulges the contents of private meetings and private discussions. These meetings and discussions were conducted in the public interest, and involved tens of billions of public dollars, but apparently the public has no right to know what went on in them. McElroy interviews people for a living, and touts his show as “uncensored.” He must want at least some people to talk. Why not Rattner?

Rattner’s character isn’t a sufficient reason. Everyone in the auto industry isn’t squeaky clean, but dirty laundry tends to be ignored. Rattner is a special case.

What makes Rattner special? I don’t know, but can hypothesize.

Rattner was and remains an outsider who by his own admission knew nothing about the auto industry. The latter proves a non-issue. I’m generally skeptical of the entire concept of “quick studies,” but Rattner almost makes me a believer. The book includes accurate insights about how GM and Chrysler operate that have seemingly eluded the bulk of the auto industry press for decades. For example, “nothing happens at GM without PowerPoint,” labor was being treated as a fixed cost with absurd consequences, and the “grin fucking” “culture of mediocrity” couldn’t handle open conflicts, preferring to let things drag out forever behind the scenes. In comparison, the UAW’s leadership seemed knowledgeable and realistic once out of view of the membership. They had a better grasp of GM’s situation than GM’s leaders did, and behind the scenes were interested in working out a viable solution.

Unlike a journalist who must maintain access to sources, Rattner clearly felt free to communicate what he and other insiders observed. Such as the Treasury Secretary Paulson’s initial reaction to GM’s initial request for help: “This is complete bullshit!” And Rahm Emanuel’s reaction to the supposed need to save union jobs: “Fuck the UAW.” (Was the latter said and then written for the sake of appearances? Perhaps.) In true “kiss and tell” fashion, names are named, and Rattner colorfully expresses his personal opinions of various players. A violation of insider etiquette? No doubt. But we learn much more as a result.

Perhaps the largest revelation: GM possessed a very weak grasp of its finances and cash position, and was repeatedly unable to answer basic financial questions. GM’s leaders “seemed to be living in a fantasy world” and refused to consider bankruptcy, even though a bankruptcy seemed virtually certain to the task force. (The goal of the task force nearly from the start was not to avoid bankruptcy, but to avoid an uncontrolled bankruptcy.) For these reasons, Rattner repeatedly characterizes GM’s top executives, and especially CFO Ray Young “whose lack of common sense seemed limitless,” as incompetent. And yet he also gives GM’s leaders credit where it is due, noting that GM’s manufacturing operations were much more efficient than the task force initially assumed, and that there was thus no fundamental reason it couldn’t compete.

Worse than being an ignorant outsider, Rattner was from Wall Street, the worst sort of outsider. His New York personality tends to rub Midwesterners the wrong way. They—and I do mean they, McElroy is far from alone in his opinion—don’t like him.

Adding insult to injury, this unlikable outsider decided he could overhaul the auto industry without relying heavily on insiders. Rattner acknowledges that the team received “much unsolicited advice,” but found many of the suggestions “impractical.” In general insiders were seen as too wedded to how things had been done and so incapable of envisioning much less producing the necessary changes. Some insiders with advice (or more) to offer might have felt slighted.

Some have argued that Rattner’s book is overly self-serving. They must have read a different book than I did—if they read it at all. Rattner rarely takes personal credit for the accomplishments of the task force, instead ascribing nearly all of them to other members, especially labor expert Ron Bloom, corporate restructuring expert (and Republican) Harry Wilson, and bankruptcy expert Matt Feldman. Bloom took the lead on Chrysler, while Wilson did the same with GM.

Rattner describes some conflicts within the task force. Some members, most prominently Wilson, wanted to kill Chrysler, partly because the case for saving it was weak, partly to give GM a better shot at success. The decision to instead save Chrysler was ultimately made by Obama, and by the slimmest of margins. Rattner doesn’t conceal his distaste for Sergio Marchionne, who apparently tried to use the unbeatable hand the government dealt him to bully the other parties into submission. After Chrysler was taken care of, Bloom tried to assume an equally prominent role in the GM overhaul, which brought him into conflict with Wilson.

We’ve heard a lot about how badly bondholders were treated, but Rattner convincingly argues that they’ve actually received more than they should have. If the companies had liquidated, debt holders would have received very little, perhaps even nothing in the case of GM’s bondholders. Only the government’s desire to save the companies from liquidation gave them any reason to expect more. They knew that every day the situation remained unresolved would cost the government tens of millions of dollars. So by threatening to delay a resolution they hoped to force the government to pay them off. The task force called their bluff and managed a quick resolution through the bankruptcy courts, where the judges prioritized keeping the companies alive. As part of the process the debt holders ended up receiving considerably more than Rattner strongly felt they deserved. They received their payoff, just not as large a payoff as they dreamed of receiving.

Rattner does take personal credit (blame?) for one thing he felt needed to be change, but that insiders were not going to change. New investors in troubled companies often replace the top executives, and the government was serving as GM’s investor of last resort. So, acting much like a private equity investor, Rattner personally fired GM CEO Rick Wagoner, and stepped up to take the resulting flack. Many prominent members of the automotive press liked Wagoner. And, even if they hadn’t, they don’t like the idea of outsiders firing insiders. Prominent members of the press likely think of themselves as insiders, and c losely identify with the executives they cover. Powerful outsiders like Rattner are the common enemy.

Rattner doesn’t pretend that the outcome was perfect. Though Obama is generally portrayed in a good light, the president is criticized for one thing: refusing to jointly work with the Bush administration on the crisis. In Rattner’s view, the “one president at a time” mantra cost taxpayers billions by delaying the bankruptcies. Another indication that the book is not political, Rattner praises Republican senator Corker for attempting to use the crisis to force needed changes, and credits him for laying down guidelines that shaped the outcome.

Rattner also wishes more could have been done to wring concessions from the UAW, especially with regard to the pension plan, and to change the culture at GM. He criticizes the UAW for selling out new hires in order to protect the wages of existing workers. And, at the end of the book, the question of who can and should lead GM remains undecided, with Henderson and Whitacre (the latter the task force’s last chance to effect meaningful cultural change within GM) both out after short terms.

But, by his own admission, Rattner’s a pragmatist. He realizes that the outcome is never going to be perfect, and that insisting on a perfect outcome likely would have resulted in a much worse outcome for all involved. The major achievement of the task force was forcing everyone to accept a less than ideal outcome from their own perspective, to share the pain—which had not been done with the financial industry bail out. Given huge problems decades in the making and just a few months to solve them, the task force achieved much more than anyone could have expected it to without the benefit of hindsight. It’s easy to forget how impossible a GM bankruptcy seemed to most people, especially those leading GM but also much of the auto industry media, before the fact.

Rattner doesn’t pretend that politics were not a factor. Some actions are described as politically-motivated, most notably the government’s insistence that GM’s headquarters remain in downtown Detroit and GM’s early repayment of some of the money—by using some of the money. Senator Barney Frank got GM to delay the closing of a small parts depot in his state. Some proposed actions fail what Rattner labels “the Washingon Post test:” how would they appear on the front page of the paper? But these were exceptions, not the rule. Rattner did what he could to minimize the role of politics, and largely succeeded.

Are there things Rattner is not telling us? No doubt. For example, it’s possible that Obama was more involved in some of the task force’s more controversial actions, such as the firing of Wagoner, and that Rattner is continuing his role of shielding the president from criticism. In general Rattner says little about what might have been his primary function, buffering the rest of the team from politicians and other parties interested in influencing the outcome so members could do their jobs. But overall I find Rattner’s book as complete and lacking in extraneous bias as an insider account could possibly be. For once we’re not entirely stuck on the outside, wondering, “What were they thinking?” It no doubt helped that Rattner’s position was temporary, and that he does not have to continue to work with the people portrayed in the book.

No one likes being told what to do by an outsider, even (especially?) when they know the outsider is right. Rattner’s book now serves as a well-researched and well-written permanent record of this outside intervention, and how well it worked. Since the book itself is unassailable, Rattner’s character becomes the target. I, for one, generally dislike character-based attacks, and would like to see such an informative insider account properly rewarded.

If you feel the same, buy the book.

Michael Karesh owns and operates TrueDelta, an online source of automotive pricing and reliability data

Michael Karesh lives in West Bloomfield, Michigan, with his wife and three children. In 2003 he received a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. While in Chicago he worked at the National Opinion Research Center, a leader in the field of survey research. For his doctoral thesis, he spent a year-and-a-half inside an automaker studying how and how well it understood consumers when developing new products. While pursuing the degree he taught consumer behavior and product development at Oakland University. Since 1999, he has contributed auto reviews to Epinions, where he is currently one of two people in charge of the autos section. Since earning the degree he has continued to care for his children (school, gymnastics, tae-kwan-do...) and write reviews for Epinions and, more recently, The Truth About Cars while developing TrueDelta, a vehicle reliability and price comparison site.

More by Michael Karesh

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Formula m For the gas versions I like the Honda CRV. Haven’t driven the hybrids yet.

- SCE to AUX All that lift makes for an easy rollover of your $70k truck.

- SCE to AUX My son cross-shopped the RAV4 and Model Y, then bought the Y. To their surprise, they hated the RAV4.

- SCE to AUX I'm already driving the cheap EV (19 Ioniq EV).$30k MSRP in late 2018, $23k after subsidy at lease (no tax hassle)$549/year insurance$40 in electricity to drive 1000 miles/month66k miles, no range lossAffordable 16" tiresVirtually no maintenance expensesHyundai (for example) has dramatically cut prices on their EVs, so you can get a 361-mile Ioniq 6 in the high 30s right now.But ask me if I'd go to the Subaru brand if one was affordable, and the answer is no.

- David Murilee Martin, These Toyota Vans were absolute garbage. As the labor even basic service cost 400% as much as servicing a VW Vanagon or American minivan. A skilled Toyota tech would take about 2.5 hours just to change the air cleaner. Also they also broke often, as they overheated and warped the engine and boiled the automatic transmission...

Comments

Join the conversation

Another book that I've read is At the Crossroads: Middle America and the Battle to Save the Auto Industry, by Abe Aemidor and Ted Evanoff. It's written from the standpoint of several communities in Indiana - autoworkers, local governments, some companies, so it adds a different dimension from Wall Street and the Federal Government. I found it very interesting - about how some small town mayors who are trying to adjust to the large economic forces affecting their communities. What struck me greatly about the book was that they brought up a really good point - whether you like or didn't like the Federal assistance to the automobile industry, there was no grand plan or design for American industrial policy in the future, seems like the US government is being reactive and just trying do a band aid to save the industry. Yeah, I know industrial policy sounds like a dirty word for adherants of laissez faire capitalism, but maybe we need to revisit that.

Ditto. Thank you for a great review, Mr. Karesh. I offered to do one for Mr. Niedermeyer, but reading yours I can only say you did a much better than I could have. "The truth? You can't handle the truth."For all their big talk and criticism, McElroy (and Sweet Pete DeLorenzo) are really just Detroit apologists and a--kissers at heart. Otherwise, they wouldn't be so scared of a twerp like Rattner at the DEC. Sweet Pete in particular is long overdue for an ass-whupping, but I suspect ignoring him is the better strategy. And at this point, Buickman's once sensible comments are no longer valid. He's just plain nuts.