Book Review: Can-Am Cars In Detail

Handed out to undeserved recipients and devalued by lazy writers alike, few words are as hackneyed as iconic or legendary. If everything is an iconic legend, nothing is. Sometimes, though, the words are exactly appropriate. The Canadian American Challenge Cup racing series which ran from 1966 to 1974, more popularly known simply as Can-Am, included cars and drivers that are truly iconic and the series was genuinely the stuff of legend. Though the big block V8 engines of Can-Am last roared over 35 years ago, even today the name Can-Am resonates strongly with car enthusiasts.

Attracted by an almost unlimited technical formula and some of the era’s richest purses, the world’s most innovative constructors and talented drivers flocked to the series. Team owners that have since succeeded in other series like Roger Penske, Jim Hall, Paul Newman and Carl Haas, were active in Can-Am. This was when drivers were not specialists who only raced in this or that series, and many of the Can-Am drivers also raced in Formula One. Not only were some of the drivers the same in both F1 and Can-Am, the two series also raced on some of the same tracks. The Can-Am cars were so technologically advanced, so powerful and so fast that the F1 drivers typically set faster times with their Can-Am cars than with their F1 rides. The series produced technical advancements that still impact racing. Can-Am was so larger than life, that it eventually produced the most powerful car ever designed to race on a closed course, a car which so dominated the series, it is said to have killed that very racing series that spawned it. As I said, the stuff of legend.

Befitting such a larger than life subject, one of the truly golden ages of 20th century auto racing, David Bull Publishing has released Can-Am Cars In Detail: Machines And Minds Racing Unrestrained, with photos by Peter Harholdt and text by respected racing journalist Pete Lyons. It’s a large format book, ~ 11″X11″, hardcover, 244 pages, with a slip case. Noted in passing is that this is yet another graphically rich book printed in China. Apparently the publishing industry is outsourcing to China too.

Because of the large format I’m tempted to call CACID a coffee table book but that would be doing Lyons and Harholdt and their publisher a huge disservice. Yes the book has gorgeous, large photographs of 22 of the coolest cars ever built, all either restored, as-raced or in one case, recreated, but it’s much more than a picture book. CACID gives a vivid sense of what Can-Am was like, showing the variety of cars raced (with their achievements or lack thereof), and their chronological development. What makes CACID different than more cursory looks at Can-Am is that in addition to the legendary Can-Am cars that everyone recognizes, like the Chaparral 2E, Lola T70, McLaren 6 and 8 models, and Porsche 917s, there are lesser remembered marques like Genie, Caldwell, McKee and Honker. Honker? There are cars that won races and championships, cars that were innovative but not very successful, and some backmarkers as well. Lyons and Harholdt’s selection of cars gives a comprehensive view of the series. The “In Detail” part is no brag, just fact. Harholdt’s photographs are visually arresting, the framing and lighting present the cars like the mechanical art that they are, and Lyons’ text treats each car’s racing history in a manner that gives a very complete history of the individual cars, their constructors and the series overall.

You get a visual taste of what’s inside before you even start to read. The slip case is wrapped with a large photo of Denny Hulme’s McLaren M8F, while the book’s jacket cover has a cropped photo of the unequal length and canted velocity stacks of the McLaren M20’s 565 cubic inch (9.26L) Chevy V8 (I told you they were big blocks). Framed by the car’s back wing (one of Can-Am’s many innovations), the brushed aluminum stacks look like sculpture. Inside the book on the page facing the table of contents is a full page photo of the all aluminum Holman-Moody Ford V8 from the Ford 429’er, one of the lesser known cars covered in the book. Based, somehow, on the cast iron production 429, this engine actually displaced 494CI. I hate to be trite and keep using words like stunning and arresting, but Harholdt’s photographs are top shelf car porn. The photographs appear to have been studio shot and the book could not have been possible without the cooperation of the owners of some irreplaceable cars.

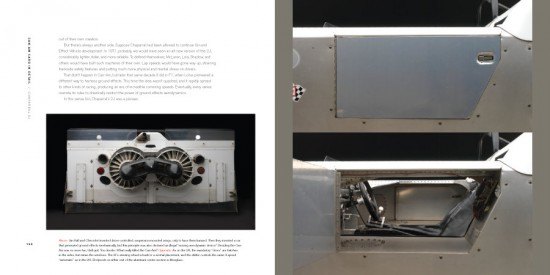

The book is arranged chronologically, starting with 1966’s Chaparral 2E and ending with the Shadow DN4 that raced in the half-finished 1974 season. Thanks to owners’ foresight, vintage racing and the recognized value of vintage race cars to collectors’, a representative example of the racing hardware used in the Can-Am series still exists today, making the authors’ task a bit easier. Jim Hall’s race shop restored examples of all of his Chaparrals, which are represented in CACID by the 2E, (of which you can buy Hall-built exact replicas), the radical slipstream 2H, and the vacuum downforce and ultimately banned 2J. The Chaparrals were so innovative that some of their best known advancements contain fascinating subdetails. The 2E is usually noted for introducing high mounted wings to racing cars. Many also know that the 2E’s wing was under driver control, with high downforce in corners and trimmed for low drag on the straights. Driver control with a foot pedal was possible because the Chaparrals had torque converters, not clutches. A detail that is not as well known is the fact that the 2E’s wing struts were not mounted on the body, but rather to the wheel hubs, so the wing didn’t affect spring loading, it applied downforce directly to the tires. Wheel manufacturers and car companies alike imitated the 2E’s cast spoke wheel design. Hall has joked that if he’d bothered to copyright the design, he’d have made more money in royalties from BBS alone than he made racing cars.

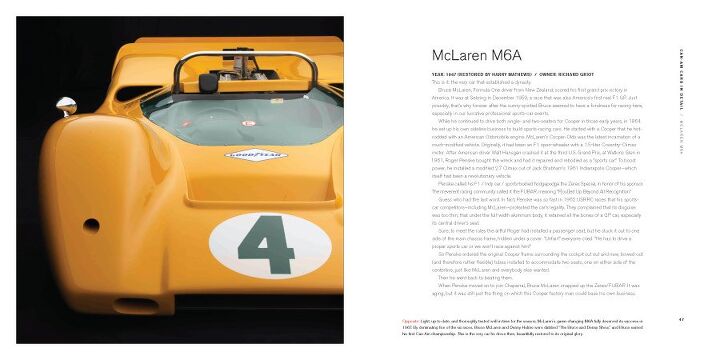

Hall’s white cars were innovative, yet weren’t terribly successful in Can-Am, and he constantly butted heads with scrutineers as the series became increasingly concerned with rules. Bruce McLaren’s orange cars were more conventional (though just as beautiful), and they dominated the series, winning many races, often finishing 1-2 with McLaren and Hulme trading podium spots back and forth, and multiple championships. The book includes the M6A, and M8B McLarens in addition to the aforementioned M8F, and M20.

The relatively loose rules in Can-Am meant competitors were always looking for out of the box ideas for more speed. Based on the idea that minimal frontal area and a low profile meant maximum straightline speed, the AVS Shadow Mk 1, from 1969-70, used so-called “tiny tires”, about 30% less tall than other tires then used in Can-Am. The Shadow probably influenced the Tyrell six-wheeler raced later in F1.

There are three of Eric Broadley’s Lolas including the definition-of-automotive-beauty T70, and Ferrari is represented by the 612P, in unrestored condition as Chris Amon last raced it in 1971.

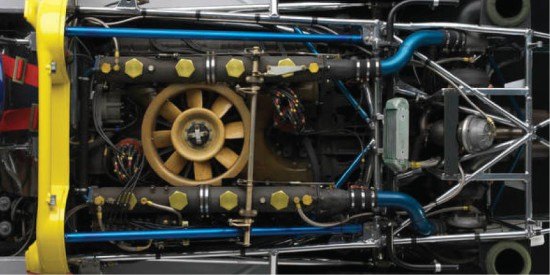

Porsche is represented by three iterations of the 917, the 917PA, the 917/10K, and the uber Porsche, the Mark Donohue / Roger Penske 917/30. The 917/30, at 1,100 horsepower, is acknowledged to be the most powerful closed course race car ever. Chew on that for a second. In almost 40 years, a more powerful race car, at least not one that had to turn right or left, has not been made. There has simply been nothing like the 917/30, then or now. Donohue was closely involved in the development of the car. The 917/30 had a driver controlled waste gate on the turbos that would give him about 1500 HP on demand and a driver adjustable rear sway bar that gave oversteer on demand. Donohue called it the “perfect race car”, and a “monument” to his career, already much accomplished.

To say that the 917/30 dominated Can-Am in 1973 is to state the obvious. Called by some “the car that killed Can-Am”, the 917/30 was so unlimited that it made a mockery not just of the car’s competition but of the concept of competition itself. More dominant than Ferrari in Schumacher’s time. Eight races, eight poles, six victories, one championship. The particular 917/30 in CACID was built for Donohue to use in the 1974 season and is finished in the Penske team’s blue and yellow Sunoco livery. He never drove this car, though. After winning the Can-Am championship in 1973 with the 917/30 and a remarkable 38% of the races that he entered in his career, Donohue retired from driving (he later came back to race in F1 for Penske, a decision that was ultimately and sadly fatal).

This 917/30 was formerly owned by the Porsche factory museum. Current owner Matt Drendel thinks he’s the luckiest man in the world. “What’s it like to drive? I get asked that a lot. It’s like a LearJet on takeoff. It feels like it’s never running out of power, and it feels like that in every gear. It feels like you’re being pushed by the hand of God. One time I floored it in second gear and the front wheels came off the ground!” The 917/30 is not an economy car but Drendel makes it sound like spending $1,000 on racing fuel for 90 minutes on the track with the 917/30 is more cost effective in terms of mental health than a year’s worth of 50 minute sessions with a shrink.

Can-Am wasn’t just about the cars. The drivers were among the greatest ever. The starting grid of just abut any race in the series’ history reads like a motorsports hall of fame roster. Represented in the book along with Hall (he’d previously won a US road racing championship) and McLaren, are Denny Hulme, Dan Gurney, Phil Hill, John Surtees, Mario Andretti (who drove a couple of the cars in the book, including a Honker owned by Paul Newman), Sam Posey (he still owns the Caldwell D7 he raced in Can-Am), Chris Amon, Vic Elford, George Follmer, Pedro Rodriguez, David Hobbs, Jody Scheckter, Brian Redman and of course the aforementioned Mark Donohue. Again, the stuff of legends.

At $100, Can-Am Cars In Detail is not cheap but it’s exceptionally well written, with first rate photography and the book is a good value if you’re at all interested in auto racing history. It seems that most contemporary racing series are infected with ennui or malaise. Formula One, NASCAR, IndyCar, all are targets of substantial and substantive criticism. Bernie Ecclestone, Brian France and Randy Bernard can all easily afford to spend a hundred bucks. If they want to get an idea what an exciting racing series looked like, and more importantly felt like, they could do much worse than pop for a copy of Lyons and Harholdt’s book.

Ronnie Schreiber edits Cars In Depth, the original 3D car site.

More by Ronnie Schreiber

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- SCE to AUX The nose went from terrible to weird.

- Chris P Bacon I'm not a fan of either, but if I had to choose, it would be the RAV. It's built for the long run with a NA engine and an 8 speed transmission. The Honda with a turbo and CVT might still last as long, but maintenance is going to cost more to get to 200000 miles for sure. The Honda is built for the first owner to lease and give back in 36 months. The Toyota is built to own and pass down.

- Dwford Ford's management change their plans like they change their underwear. Where were all the prototypes of the larger EVs that were supposed to come out next year? Or for the next gen EV truck? Nowhere to be seen. Now those vaporware models are on the back burner to pursue cheaper models. Yeah, ok.

- Wjtinfwb My comment about "missing the mark" was directed at, of the mentioned cars, none created huge demand or excitement once they were introduced. All three had some cool aspects; Thunderbird was pretty good exterior, let down by the Lincoln LS dash and the fairly weak 3.9L V8 at launch. The Prowler was super cool and unique, only the little nerf bumpers spoiled the exterior and of course the V6 was a huge letdown. SSR had the beans, but in my opinion was spoiled by the tonneau cover over the bed. Remove the cover, finish the bed with some teak or walnut and I think it could have been more appealing. All three were targeting a very small market (expensive 2-seaters without a prestige badge) which probably contributed. The PT Cruiser succeeded in this space by being both more practical and cheap. Of the three, I'd still like to have a Thunderbird in my garage in a classic color like the silver/green metallic offered in the later years.

- D Screw Tesla. There are millions of affordable EVs already in use and widely available. Commonly seen in Peachtree City, GA, and The Villages, FL, they are cheap, convenient, and fun. We just need more municipalities to accept them. If they'll allow AVs on the road, why not golf cars?

Comments

Join the conversation

BTU content would certainly contain speed, assuming the limits are set low enough. It essentially puts a mileage cap on the cars. I doubt you're going to get 1500 bhp cars running 200 mph if there's a hard limit of lets say 10 mpg (or diesel equivalent -- thus it's a BTU cap rather than mileage cap, if you just said 10mpg all cars would be diesel because of the higher BTUs of the fuel). An advantage of the cap would be to get manufacturers to start thinking of ways to cheat friction, some of which may work its way into our road cars. The trick would be to set the BTU cap high enough to get speeds up, but low enough to keep things relatively safe. I'm not so sure it would limit costs as well as speeds, as you can do all sorts of expensive things to get better mileage, with carbon fiber and whatnot.

I consider myself blessed that my father brought me to several Can-Am races when I was a wee lad. I saw many legends fly by me at speed with a thunder that will never be heard again on this planet.