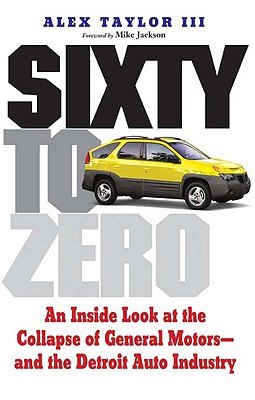

Book Review: Sixty To Zero [Part II]

Editor’s Note: Part One of Michael Karesh’s review of Sixty To Zero can be found here.

Journalists write stories. A coherent story is a partial truth at best. If it’s portrayed as the whole story, it’s a lie.

In Sixty to Zero, veteran auto industry journalist Alex Taylor III provides an unusual level of insight into the relationships between top auto industry journalists and the executives they cover. He acknowledges getting too close to these executives more than once, and blames this for several embarrassingly off-base articles. But even in his most self-reflective moments, Taylor fails to recognize an even larger source of distortion.

Taylor’s explanation for the collapse of GM is simple: the company’s senior executives were removed from reality, wedded to the past, and unwilling to act quickly and decisively to fix their firms’ mounting problems. Ford’s Mulally, according to Taylor, indicates the path Wagoner should have taken at GM. Though true to a point, this explanation doesn’t nearly go far enough. It’s not only simple, it’s too simple.

In Taylor’s view, “the history of nearly every auto company revolves around the CEO.” He has sought and received far less contact with people lower in the auto company organizations—even Bob Lutz, since he was merely a vice chairman, is a “lesser executive” who normally would not have received frequent press attention.

Why such a strong focus on the CEO? For starters, Taylor is clearly moved by status and prestige, the qualities embodied by the CEO position. Taylor’s approach to journalism is also strongly influenced by the desire to tell a good story and sell magazines. Individuals are easier to understand and more enjoyable to write and read about than teams or organizations. Just as Taylor was most interested in talking to CEOs, readers tend to be most interested in reading about CEOs.

Taylor does note in passing that the role of the CEO has been exaggerated: “When a company is performing well, there is an understandable impulse to attribute the success to the CEO and to examine his actions in light of that.” He also notes that “projecting the capabilities of the CEO onto an entire management is especially problematic for a company as large and complex as GM.” Despite these realizations, however, Taylor continued to do both.

Most of all, Taylor never seems to fully grasp that CEOs—even the good ones—have a severely limited and distorted view of what goes on inside their companies. The ideal access he describes, to shadow the CEO as he goes about his daily work, is a step in the right direction. With such access, he might see what a CEO actually says and does, and not have to rely on what the CEO claims, in interviews, to be saying and doing. But even if the CEO does and says what he would normally do and say while being shadowed, this assumes that all of the important activities inside these companies involve the CEO, or at least occur with the CEO in the room.

I must admit to an unfair advantage. Back in the late 1990s I spent 18 months practically living inside various parts of General Motors while conducting field research for my Ph.D. thesis. I attended over 400 working-level meetings within program management, design, marketing, and engineering, and spent entire days as a fly on the wall inside the Design Center. I rarely saw a senior executive. I never saw the CEO.

In one instance, Taylor shadowed Wagoner during a meeting with design executives. But did the real design work happen with Wagoner in the room? Should it have? During the days I spent inside GM, real work only happened when executives were not in the room. When the executives arrived, the real work stopped and the “dog and pony show” began. Beyond this, it quickly became apparent that within GM, and I later learned within just about any organization of any size, scant information makes it up even two levels, much less all the way from the product development teams to the CEO. Whatever information does make it has been heavily massaged. By continuously relying on CEOs as his predominant source of information, Taylor has been fated to keep repeating the same mistakes.

Compounding the problem, Taylor and his colleagues influence the industry that they cover. Executives want to have positive articles written about them, and so further exaggerate how much they can personally know and do. No one gets positive press by acknowledging their limits. After one debacle, GM’s Jack Smith continued to assert that he was well-informed about what was going throughout the organization, as if this were really possible, and tht he was not “out of the loop.” Wagoner convinced Taylor that “he was no forty-thousand-foot manager; he was intimately involved in key areas of the business” and comfortably interacting with everyone from engineers to dealers. Taylor never appears to have tested such claims by actually talking with people lower in the organization.

This exaggeration of the CEO’s role and the CEO’s abilities has been repeatedly validated by the resulting magazine articles. Cults of the CEO have been born and sustained. Encouraged by the press, auto companies concentrate decision-making (or a lack thereof) at the top of the organization even more than they might otherwise.

What both the journalists and most CEOs miss: the best senior executives develop teams of experts much lower in the organization, enable these teams to do their jobs well, then let them do their jobs. Mulally has made some tough decisions at Ford, but he has also focused on eliminating infighting and building teamwork within the organization. Mulally isn’t a car guy, and he knows he’s not a car guy. If he’s as smart as he’s reputed to be, he lets the car guys lower in the organization do their jobs without even pretending to be intimately involved in what they do.

Unfortunately, this isn’t the story one is likely to hear while interviewing a senior executive. Even if the executive does talk about “the organization,” such an account cannot compete with the portrayal of an individual executive for color and doesn’t make for a dramatic article the way killing a brand, publicly taking on the UAW, or a “ritual firing” does. Taylor repeatedly wishes for more “ritual firings”—his term, not mine.

The unrecognized problem with ritual firings: at best they assume that the individual fired was responsible for the mistake, and that other individuals would not have made the same mistake. At worst, they realize this, but don’t care. It’s just fun to watch heads roll. Taylor notes that executive firings were historically much more common at Ford, and that Mulally’s suppression of political infighting improved the company’s performance. Strangely, Taylor does not seem to learn from this that ritual firings don’t improve company performance.

Taylor also calls for auto company CEOs to take more risks, but this seems more than a little cliché. What sort of risks would he have them take? Jack Smith and Rick Wagoner get little credit for GM’s big bet on China. Don Peterson gets labeled an odd “iconoclast” for taking Ford in unusual directions. Roger Smith took many risks while CEO of GM, and gets severely criticized for each of them. Lutz receives mild praise for having some minor successes while avoiding disasters. Taylor wants risks without failures. But the real possibility of failure is what makes a risk a risk.

Taylor’s suggestions that executives should both take more risks and fire more people for mistakes comprise a recipe for firing lots of people. The “ritual firings” he wishes for would discourage the risk-taking he also wishes for. These are contradictory recommendations.

In reality, while there are some bad executives, all too often there are good executives placed within social systems that make it virtually impossible to make good decisions. Unless senior executives fix the underlying problem, which is the organization, not the individuals within it, they’ll just keep firing executive after executive.

Auto industry journalists like Taylor, by celebrating CEOs and largely ignoring the rest of the large organizations they lead, and by repeatedly focusing on the symptoms rather than the underlying problem, have themselves been part of the problem.

By focusing so intently on CEOs, and relying on interviews with them as his primary sources of information, Taylor has, without ever realizing it, spent decades building overly close relationships with the wrong people. Assuming, of course, that the goal was to accurately report what was going on inside these companies, and not making friends with important people in the process of selling more magazines.

I’d like to learn what’s really going on inside these companies, and how and how well they’re actually operating. Such a story makes it into the automotive press perhaps once every five to ten years. We have had insiders share bits of their knowledge, insights, and perspective here at TTAC from time to time. But true investigative journalism, where a writer builds relationships with people throughout these large organizations, and is able to report what’s really going on as a result? There are a number of reasons this still hasn’t happened—among them the very real possibility of “witch hunts” like the one Taylor describes—but I’m still hoping.

Michael Karesh lives in West Bloomfield, Michigan, with his wife and three children. In 2003 he received a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. While in Chicago he worked at the National Opinion Research Center, a leader in the field of survey research. For his doctoral thesis, he spent a year-and-a-half inside an automaker studying how and how well it understood consumers when developing new products. While pursuing the degree he taught consumer behavior and product development at Oakland University. Since 1999, he has contributed auto reviews to Epinions, where he is currently one of two people in charge of the autos section. Since earning the degree he has continued to care for his children (school, gymnastics, tae-kwan-do...) and write reviews for Epinions and, more recently, The Truth About Cars while developing TrueDelta, a vehicle reliability and price comparison site.

More by Michael Karesh

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Tassos Jong-iL Not all martyrs see divinity, but at least you tried.

- ChristianWimmer My girlfriend has a BMW i3S. She has no garage. Her car parks on the street in front of her apartment throughout the year. The closest charging station in her neighborhood is about 1 kilometer away. She has no EV-charging at work.When her charge is low and she’s on the way home, she will visit that closest 1 km away charger (which can charge two cars) , park her car there (if it’s not occupied) and then she has two hours time to charge her car before she is by law required to move. After hooking up her car to the charger, she has to walk that 1 km home and go back in 2 hours. It’s not practical for sure and she does find it annoying.Her daily trip to work is about 8 km. The 225 km range of her BMW i3S will last her for a week or two and that’s fine for her. I would never be able to handle this “stress”. I prefer pulling up to a gas station, spend barely 2 minutes filling up my small 53 liter fuel tank, pay for the gas and then manage almost 720 km range in my 25-35% thermal efficient internal combustion engine vehicle.

- Tassos Jong-iL Here in North Korea we are lucky to have any tires.

- Drnoose Tim, perhaps you should prepare for a conversation like that BEFORE you go on. The reality is, range and charging is everything, and you know that. Better luck next time!

- Buickman burn that oil!

Comments

Join the conversation

The disconnect between the upper management and everyone else in these companies is amazing. I worked at a large company for several years, one that made building materials. Anyone who made it to the "top floor" who dared to tell the board what was really going on would be dooming themselves. It happened a couple of times where someone would just say what was going to happen, and it always did happen, exactly as they claimed it would. The next thing you know, out the door they went. The heir apparent to the throne got booted when he said that the company should just accept the obvious, that bankruptcy was unavoidable, and they should file it right now, while the economy was doing well. Less than a month later, he was sent on his way, several million richer, and was soon hired by a competing company, once his "no compete" clause ran out. The CEO of the company basically did two things, he made speeches at various places around the country (and sometimes out of the country) to local business associations, and play golf. This was basically a pretense to do what he really went there to do, play golf, and lots of it. Golf, all the time, golf. He hired a "hit man" to do all the firings, as he was a "nice guy", who didn't like to do any actual firing himself. The arrogance of the upper management was amazing. They laid off about 100 people, then most of the upper management spent nearly 100K each on two occasions for golf trips down South, and then out West. They were so out of touch with reality that they were shocked when there was practically a revolt over these trips. Almost everyone in the building got a detailed printout of the expenses for these trips, along with the costs of the CEO's golf trips (Almost all by corporate jet) for the last two years, and it got ugly. The printout was titled, "How many jobs could have been saved in the last year?". The person who put out all those printouts was never found, even though the crack(ed) security team tried and tried. The security manager was canned soon after he failed to find out who did it. Nobody was shocked when this happened, except him, he looked like he'd been told he had a terminal illness when he got escorted out the door one morning. The amount of money wasted by the executives on "urgent meetings" overseas, while taking their wives and kids, on the company's expense, and the general waste of money throwing perfectly good office supplies and other items away was almost comical. They also bought office supplies and computer equipment from a traditional office supply company for almost full list price, without any thought of it. I made a proposal to take over purchasing of most supplies and PCs in the US. I estimated I would save about a quarter million a year, counting my salary, in the Ohio area alone per year. I was basically laughed at, even though there was no way to dispute my numbers, as I had the prices paid, and the prices I would have paid, right there to see. I knew I had wounded myself career wise, and soon left. The CEO got grilled over his and his "team's" "throwing money" away playing golf while laying off people by several people at the stockholder's meeting, and it was amusing to watch the video of it and see him squirm, and try to spin it. He also made several attempts to convince hostile employees that all his trips were primarily business related. I don't think anyone bought it, and it was very entertaining to watch him crack jokes to an audience who was way too quiet. The flop sweat was amazing. All of this was happening while the company was struggling to stay out of bankruptcy. It didn't make it, but is doing ok now, over a decade later. The CEO retired a few years later, and got a nice payout when he went off to golf to his heart's content, less corporate jet, and all expenses paid. Most of the "golf team" is still there, one of them is now the big cheese himself, but golf outings are done a different way now, there's no printouts to come back and haunt them now, the trips are paid for a different way, so to avoid such "unpleasantness" in the future.

CEOs (good ones anyway) are constantly trying to break the VP layer of misinformation. One way is to hire mgmt consultants (roll eyes here). Another is to force out people and hire your cronies (more common) Good companies work in spite of people in mgmt