Chrysler Suicide Watch 50: RIP

Chrysler’s logo should have been a bottle of lithium, rather than the Pentastar. It suffered from severe bipolar disorder all its life, and, sadly, died from it at its own hands. Like many suicidal bipolars (e.g., Van Gogh, Hemingway, Virgina Woolf), Chrysler’s many crashes and acts of self-mutilation were punctuated by fantastic highs of brilliant engineering, design and creativity. Chrysler has taken us on quite the roller coaster ride. And now it’s over. As we stumble out of our (Hemi-powered) coaster car, we’re left with an intense mixture of relief, thrill, and sadness.

Chrysler’s beginning was an unparalleled flash of genius and overnight success. Walter P. Chrysler had a fairy-tale career in the early automobile business, earning $10 million ($130 million today) in just three years while turning Buick into GM’s early powerhouse. Then, while running Maxwell, he launched the Chrysler line in 1924 with that just-perfect blend of advanced engineering and style.

It was a home run that catapulted Chrysler to number four out of a crowded field of 49 manufacturers. The subsequent successful launches of the low-price Plymouth, the upper-mid priced DeSoto, and the purchase of mid-priced Dodge firmly established Chrysler as a charter member of the Big Three.

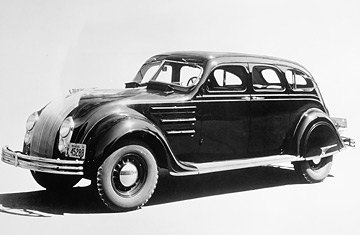

Chrysler’s first crisis came in 1934 with the failure of the radically advanced but unusual-looking Airflow. Its wholesale rejection by the buying public taught Chrysler (and Detroit) a painful lesson: avoid extreme innovation.

Chrysler recuperated and made enormous profits during the WWII era. But the development of the all-new 1949 models was haunted by Chrysler’s still-lingering Airflow insecurities. Whereas GM and Ford confidently introduced longer and lower models designed to thrill exuberant post-was buyers, Chrysler president P. T. Keller insisted on tall, boxy cars.

In the early fifties, Americans were in the mood for more—horsepower, automatics, power steering and brakes, style, and flash. Unlike Chevy and Ford, Plymouth offered none of those, and the market punished it unmercifully. In 1954, Plymouth was kicked out of its long-established number three spot by Buick and dropped to number five behind Pontiac.

The exuberant designer Virgil Exner was hired to inject vitality and fresh style. The 1955s were an improvement, but the radical 1957s were destined to be the great leap forward (“suddenly it’s 1960!”). But in the rush to revolutionize, the products were not fully developed, and suffered from atrocious build quality.

The flashy ’57s sold, but word got out and buyers punished Chrysler unmercifully. 1958 sales plunged by no less than 41% for Plymouth. And despite a reputation for engineering excellence, Chrysler would have to dodge a reputation for spotty build quality from then on, deserved or not.

Chrysler nursed itself to health once more, only to be deeply wounded by one of the most staggeringly idiotic acts of executive self-mutilation. In 1960, Chrysler president William Newberg overheard a rumor at a cocktail party that Chevrolet was working on a dramatically smaller 1962 model (it was: the compact Chevy II).

In a colossal blunder, he assumed this referred to the full-sized Chevrolets. Newberg killed development of the full size 1962 Plymouths and Dodges and initiated a crash program for substantially downsized replacements. When the ugly, truncated ’62s were first shown to dealers, an uproar ensued, and twenty dealers cancelled their franchises on the spot. Plymouth crashed to ninth place, while GM’s market share rose to an all-time peak of 52%.

Chrysler barely survived the fiasco but went on to enjoy a relatively long spell of good health from the mid-60s through 1974, in part thanks to its successful performance image. But with a portfolio of heavy RWD cars and lacking the foresight, will (and capital) to retool extensively, Chrysler was flattened by the one-two punch of the energy crises. By 1979, it was back on the critical list, saved from bankruptcy only by the life-support of a government loan-guarantee act.

This financed the compact K-car; Chrysler squeaked by and regained health, once again. Endless K-car variants carried the day. When the 1990 recession brought on another depression, Iaccoca was shown the door.

In the mid-nineties, Chrysler was on its ultimate manic high. Low overhead costs from its near-bankruptcy, some deft model development, the purchase of Jeep, and sheer luck (the boom of the truck and SUV markets) generated huge profits and a 23% market share in 1997 (bigger than GM’s recently). But at the very height of health and success, the suicidal urges return.

In 1998, CEO Robert Eaton had Chrysler engage in ritual corporate seppuku by selling itself to Daimler (while walking away with over $200 million himself). And despite all of Dr. Z’s ministrations, the patient never really regained lasting health. Was there arsenic in the Daimler medicine?

There’s a market for corpses, and Cerberus bit with all three heads at once. And choked.

More by Paul Niedermeyer

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- SCE to AUX All that lift makes for an easy rollover of your $70k truck.

- SCE to AUX My son cross-shopped the RAV4 and Model Y, then bought the Y. To their surprise, they hated the RAV4.

- SCE to AUX I'm already driving the cheap EV (19 Ioniq EV).$30k MSRP in late 2018, $23k after subsidy at lease (no tax hassle)$549/year insurance$40 in electricity to drive 1000 miles/month66k miles, no range lossAffordable 16" tiresVirtually no maintenance expensesHyundai (for example) has dramatically cut prices on their EVs, so you can get a 361-mile Ioniq 6 in the high 30s right now.But ask me if I'd go to the Subaru brand if one was affordable, and the answer is no.

- David Murilee Martin, These Toyota Vans were absolute garbage. As the labor even basic service cost 400% as much as servicing a VW Vanagon or American minivan. A skilled Toyota tech would take about 2.5 hours just to change the air cleaner. Also they also broke often, as they overheated and warped the engine and boiled the automatic transmission...

- Marcr My wife and I mostly work from home (or use public transit), the kid is grown, and we no longer do road trips of more than 150 miles or so. Our one car mostly gets used for local errands and the occasional airport pickup. The first non-Tesla, non-Mini, non-Fiat, non-Kia/Hyundai, non-GM (I do have my biases) small fun-to-drive hatchback EV with 200+ mile range, instrument display behind the wheel where it belongs and actual knobs for oft-used functions for under $35K will get our money. What we really want is a proper 21st century equivalent of the original Honda Civic. The Volvo EX30 is close and may end up being the compromise choice.

Comments

Join the conversation

One of the primary things that had kept Chrysler afloat through all the mistakes for so many years was the military division. Ever since WWII, Chrysler management could screw up as badly as they wanted so long as the military division cash-cow continued to churn out tanks for the US military. But then came the seventies' crisis and Iacocca. Lido has said in his first book that one of the most difficult decisions he had to make to keep Chrysler going was whether to continue building cars or military vehicles. Ultimately, it was the military division that went. It was the right decision for the time but, in the long run, not having the military division for the company to fall back on through the rough periods (as it had so many times in the past) would ultimately spell its doom.